THE TRAIL FROM the rim of the canyon was narrow, strewn with loose baseball-sized rocks, a sharp declination that switchbacked down. Joe carried the eagle in his arms like a baby, trying not to squeeze too hard when he misstepped on loose shale, lost his balance, and sat down hard with a thump that jarred his spine.

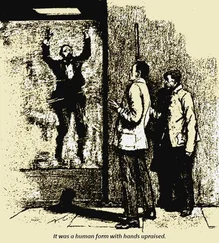

He stood up gingerly and dusted himself off, picked up the bird, and continued. It was usually at this depth into the canyon when he felt eyes on him and knew he wasn’t alone.

Tough junipers rose on either side of the trail, and in the windless still air of the canyon they smelled sharp and musky. The Hole in the Wall, because of its vertical walls and the angry stream that coursed through the floor of it and kicked up waves of moisture, was a lush green oasis in the middle of high country desert. The bottom was thick with pines, ash, and ferns, and there were birds, including bluebirds and cardinals, and reptiles he’d rarely seen in the mountain west.

At a sharp switchback shadowed by a canopy of intermarried branches from a family of aspen, whose turning leaves were weeks behind those on the surface, Joe stopped, paused, and wiped the sweat from his face with the sleeve of his shirt. He studied the trail immediately in front of him until he saw it-the glint of the trip wire. He carefully stepped over it in an exaggerated movement. There was no way, he knew, he would have seen it if he hadn’t known it was there. He had no idea what the wire connected to-bells? someone’s toe?-but he didn’t want to find out.

The unique feature of the canyon itself, and why outlaws loved it, was the naturally eroded caves in the opposite wall, their open mouths mostly hidden by brush. But from inside the caves looking out, the trail was in plain sight, a zigzag scar on the face of the canyon. In the daylight, no one could enter the canyon on the trail unobserved. And at night, there were the trip wires.

The roar of the stream increased in volume as he climbed down, and he could feel spray on his face and hands. There was a path through two-story boulders to the hissing whitewater, a crude footbridge, and the trail up the other side between the trunks of two massive ponderosa pine trees. Two hundred feet up the path, Nate Romanowski sat on a stump with his arms crossed in front of him, smirking.

“I watched you the whole time,” Nate said. “That fall was kind of comical.”

“I did it for your amusement,” Joe said.

“Was Large Merle up there watching the road?”

“Yes, he was.”

“And what did you bring me?”

“A bald eagle.”

“Ah, that’s what I thought.”

Nate Romanowski was tall, lean, with intense ice-blue eyes, a hawk nose, and long ropy muscles. He was wearing a gray flannel henley shirt and a shoulder holster for his scoped.454 Casull revolver, the second most powerful handgun in the world. As always, Joe felt the sense of calm Nate projected, a calm that could erupt into brutal violence swiftly and naturally, the way a soaring raptor would suddenly collapse its wings and drop to kill its prey in an explosion of blood and snapped bones. After Joe had cleared Nate on trumped-up murder charges years before, Nate had vowed to help protect Joe’s family. Their relationship had taken several odd and unsettling turns, but it held, and Nate was a man of his word.

“You remembered the trip wire this time,” Nate said. “That’s good, because I armed it with a shotgun.”

Joe shook his head. “Now you tell me.”

“Watch it on the way out, too.”

“I will. Do you have room for this bird?”

“What’s wrong with it?”

“A guy shot it with an arrow.”

Nate’s eyes narrowed. “Is the guy still alive?”

“I arrested him.”

Nate mock spit into dirt beside his boots to show Joe what he thought of that.

JOE FOLLOWED NATE up the trail and through a thick greasy stand of caragana. The mouth of Nate’s cave was obscured from the outside by curtains of military camouflage netting, and Nate pushed it aside so Joe could enter. Because the netting was translucent, the depths of the cave were lit in an otherworldly olive green glow, similar to what one saw through night vision goggles. It took a moment for Joe’s eyes to adjust.

“Here,” Nate said, “let me see that bird.”

Joe was grateful to hand the eagle over.

“You want your sweatshirt back?” Nate asked, pulling a wicked-looking eight-inch knife from a sheath on his belt and slicing through the duct tape.

“Yup.”

“You want the sock back?”

“You can keep it.”

“What would I want your sock for?” Nate asked.

Joe shrugged.

Nate talked to the eagle, telling it she was a pretty bird, a beautiful bird, that everything was going to be just fine now. Slowly, Nate removed the sock from her head and stared into her brilliant yellow eyes. The eagle opened her beak to screech, but Nate said, “None of that, none of that,” and the eagle kept silent.

Joe was amazed, said, “ How did you do that?”

Nate didn’t respond. He was running his hands over the eagle, talking to her, acclimating her to his touch, keeping her calm.

“How do you know she’s a she, for that matter?”

“I always know,” Nate said. “I could tell when you were carrying her.”

Joe didn’t pursue it. He watched as Nate slipped the sweatshirt off the eagle, tossing it into a heap near Joe’s feet, and continued running his hands over the bird, smoothing her feathers, pausing to feel the scarred-over entrance and exit wounds. From a bulging pocket in his cargo pants, Nate fished out leather jesses that he tied to her talons and a large tooled leather hood that he slipped over her head. He carried her to a heavy stoop made of branches with the bark still on and tied the jesses to the structure. Like a vintner slipping plastic webbing over wine bottles to keep them from clinking together in the sack, Nate gently fitted a sleeve of tight mesh over her body from her shoulders to her talons.

To Joe, he said, “She’s going to be all right, I think. You did a good job binding her up like that so the broken bones could start to knit. We’ll see in a few weeks if she can fly. This mesh sleeve will keep her from flapping her wings and breaking the bones again. Whether she can fly again will depend on how much other damage there is. I can’t fix severed tendons.”

“And if she can’t fly?”

Nate used his index finger to simulate cutting his throat. “An eagle that can’t fly is a deposed king: humiliated and useless to anybody or anything.”

AS NATE BREWED cowboy coffee in an open pot on a Coleman stove, Joe took in the cave. It was as he remembered. Gasoline-powered generator, satellite Internet, bookshelves filled with battered tomes on falconry, volumes on warfare and world history, newer books on American Indian culture and spirituality. A table and ancient four-poster bed had been left by outlaws. Near the entrance of the cave were stacks of scarred military footlockers containing clothes, equipment, food, explosives. In an alcove near the cave entrance a skinned pronghorn antelope carcass hung from a hook, the backstraps and most of a hind-quarter sliced away. Nate followed Joe’s gaze and waggled his eyebrows.

Joe said, “At least you could have pretended you weren’t poaching.”

Nate said, “My life is an open book. You just don’t want to read it.”

Joe thought, He’s right.

Nate handed Joe a cup of coffee, and Joe told Nate about the text messages. Nate had been there backing up Joe at the Sovereign camp that winter afternoon. As Joe talked, Nate’s expression never changed.

Nate said, “I’ve always wondered about that day. I was pinning down the feds, as you know, but in my peripheral vision I saw maybe a dozen snowmobiles take off into the trees. A couple of them had two or three people on them, and I remember one in particular that had some small people clinging to it.”

Читать дальше