“I am,” Binx said, and couldn’t help but smile. That’s respect in his eyes! No wonder I didn’t recognize it.

Jack nodded. “So what do you really want?”

Binx reached into the attaché case, brought out the rest of the papers, leafed through them, handed a set to Jack. “Here’s Boy.” The rest he dropped on top of the Jack history, already on the table. “All told, nine editors. A lot of stuff there. Jack.”

Jack had been smiling over the Boy story. Now he looked at Binx and said, “You’re giving me this.”

“Yes.”

“Why? What’s in it for you?”

“That’s background for your piece, research. It’s worth something.”

“Money won’t solve your problems, Binx.”

“It can help. But money isn’t all I want.”

“I didn’t think it was. What else?”

Binx gestured at the manuscript. “That’s my resume. That shows you what I can do, professionally speaking. On the basis of that. Trend can make me a roving correspondent.”

Jack slowly nodded. “Spell it out,” he said.

“A little money, not a lot. I’ve given up being greedy,” Binx said, and smiled in a new way. He drank the second grapefruit juice; it was just as good as the first. He said, “I have an idea for a story that’s right up Trend ’s alley. I’ll need travel expenses, some living expenses.”

“What is this story?”

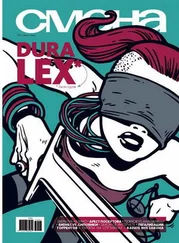

“Eastern Europe,” Binx said. “The coming of democracy and capitalism, and all of a sudden there’s a free press. Magazines and newspapers being born all over those countries, raw and new and learning how. And free . A survey piece. The free press, behind what used to be the Iron Curtain.”

Jack sat back, fingering a muffin, thinking it over. Binx drank his third grapefruit juice. It was the best of all. Jack said, “ Trend pays your expenses to Prague, Sofia, Warsaw, somewhere. You’ve got an assignment letter, letters of introduction. You’re connected.”

“Sounds good. Jack.”

“A survey piece for us, but you’re job-hunting. And they’ll like you; they’ll take you on. Not much money.”

“Don’t need much money. Jack. Not anymore.”

“Over there, you’re the old pro, the guy who knows how. Girl reporters at your feet.”

“Oh, better than that, I hope.”

A broad smile crossed Jack’s face. “I’m happy for you, Binx,” he said.

Binx’s heart leapt. “You’re going to do it.”

“Of course, I’m going to do it. Even without the blackmail, I might have done it.”

“We’ll never know.”

“So you’re getting out,” Jack said. “And you might even turn in the survey piece.”

“Stranger things have happened.”

“Not much stranger,” Jack said, and looked intently at Binx. “What about Marcie and the kids?”

Binx returned Jack’s gaze with his own level look. He’d never felt better in his life. He said, “Who?”

When Sara learned, in the Branson Beacon (reading the local newspaper was both good sense and good manners), that Ray Jones would be among the stars to appear on Sunday afternoon at a charitable fund-raiser for the local hospital, rather alarmingly named Skaggs, she knew she had to go. The setting was a big tent in the parking lot of the Grand Palace, the four-thousand-seat theater and video complex that was an elaborately pillared and porticoed white Dixie plantation house fronting a huge, sinister, featureless gray box big enough to hold all the world’s Scud missiles, as though Tara had been attached to a nuclear plant. The huge yellow-and-white-striped tent in front of this harridan with a painted face flapped in the fitful breeze, and at 12:40 Sara joined the line of families snaking slowly forward toward the volunteers at the folding tables, who took their money and peeled off little orange tickets from giant rolls. Hand-lettered red-on-white signs taped to the front of the folding tables read SUGGESTED DONATION $4.

“Press,” Sara said, an automatic reaction, when she reached the volunteer, and showed her Trend ID.

The girl, who was probably herself named Skaggs, gave Sara a look of deep dislike and mistrust. “Jested donation four dollar,” she said.

Oh well. Sara dug a five out of her wallet, handed it over, waited for change, and got an orange ticket instead. The volunteer looked past her at the next in line, and Sara said, “Could I have a receipt?”

The volunteer’s antipathy increased. “A what?”

“Oh, never mind,” Sara said, and proceeded to the entrance to the tent, where a scraggly Skaggs volunteer who was possibly trying to grow a mustache ripped her ticket in half, gave her back one part, and she entered the tent.

It was merely an open space, without seating of any kind, except for the folding chairs under the people selling T-shirts behind the trencher tables along the rear. Families milled on the blacktop under the tent, and at the far end a temporary stage had been set up, flanked by enough giant speakers and amplifiers to send a message to Mars.

Sara was lithe and slender, a rarity in that crowd. She slithered through the families, intending at first to establish herself all the way up front, but then she took another look at those speakers and amplifiers and veered off instead to a fairly quiet spot midway down the right side.

Already, children were bored and crying. Already, fathers and mothers were holding fractious infants in their arms and bouncing leadenly from foot to foot. Already, people everywhere looked as though they’d been on this death march for months. But none of them would sit down. A rock-and-roll audience, or a jazz audience, or even a classical music audience, in this situation, would arrange newspapers or jackets or something on the blacktop and sit down, but there’s a sweet instinctive formality to the country fans. Sitting on a blacktop parking lot would not be seemly, so they wouldn’t do it. They would stand, no matter. After all, suffering is the human condition, as the country families well know, here below.

The show was supposed to start at one and last an hour and a half, so as not to steal any audience from the regular commercial three o’clock shows in the theaters up and down the Strip. And by God, at exactly one o’clock, a fellow in a black frock coat and a black string tie came bounding up onto the stage, grabbed a microphone, grinned, and waited while all those hundreds of people who’d recognized him and wanted to applaud their recognition gave him an (necessarily standing) ovation. Sara realized she was undoubtedly the only person inside this tent who did not know who Mr. Frock Coat was.

She missed Jack; already she missed him. His plane out of Springfield would have been airborne for about half an hour now, on its way to St. Louis — for the change of equipment, as the airlines say, for some reason not wanting to acknowledge that they use airplanes to move people from place to place. The new equipment would take Jack to New York and their dear little apartment on West Eleventh Street. She missed him. She missed the dear little apartment. She missed New York. But mostly, she wished he were right here in Branson this second, this instant, standing next to her here inside this tent, so there’d be somebody around she could share her reactions with, someone she could understand who would understand her. It’s never an entirely comfortable feeling to be alone deep inside another tribe’s territory.

Mr. Frock Coat thanked everybody for the warm welcome. He reminded them how much Skaggs Community Hospital had done for folks over the years and he thanked them for helping to support that good work. He thanked the performers who were about to come out here and give selflessly of their time and talent so the good work of Skaggs Community Hospital could go on. And he said he didn’t want to take up any more of everybody’s time; he’d just introduce the first artist, who was Soandso !

Читать дальше