Paco Ignacio Taibo II, Eduardo Antonio Parra, Bernardo Fernández, F. G. Haghenbeck, Juan Hernández Luna, Eugenio Aguirre, Myriam Laurini, Oscar De La Borbolla, Rolo Diez, Eduardo Monteverde, Víctor Luis González, Julia Rodríguez

Mexico City Noir

***

SNOW WHITE VS. DR. FRANKENSTEIN

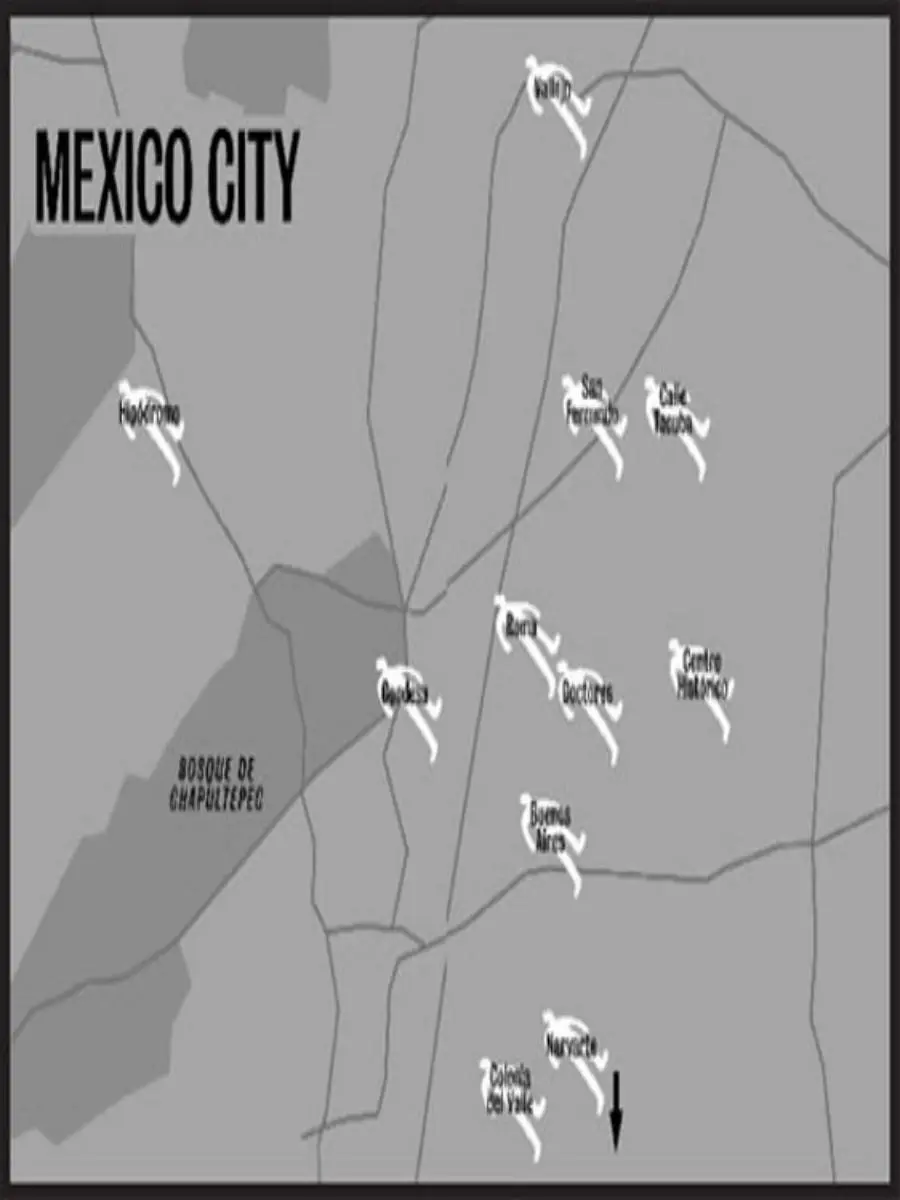

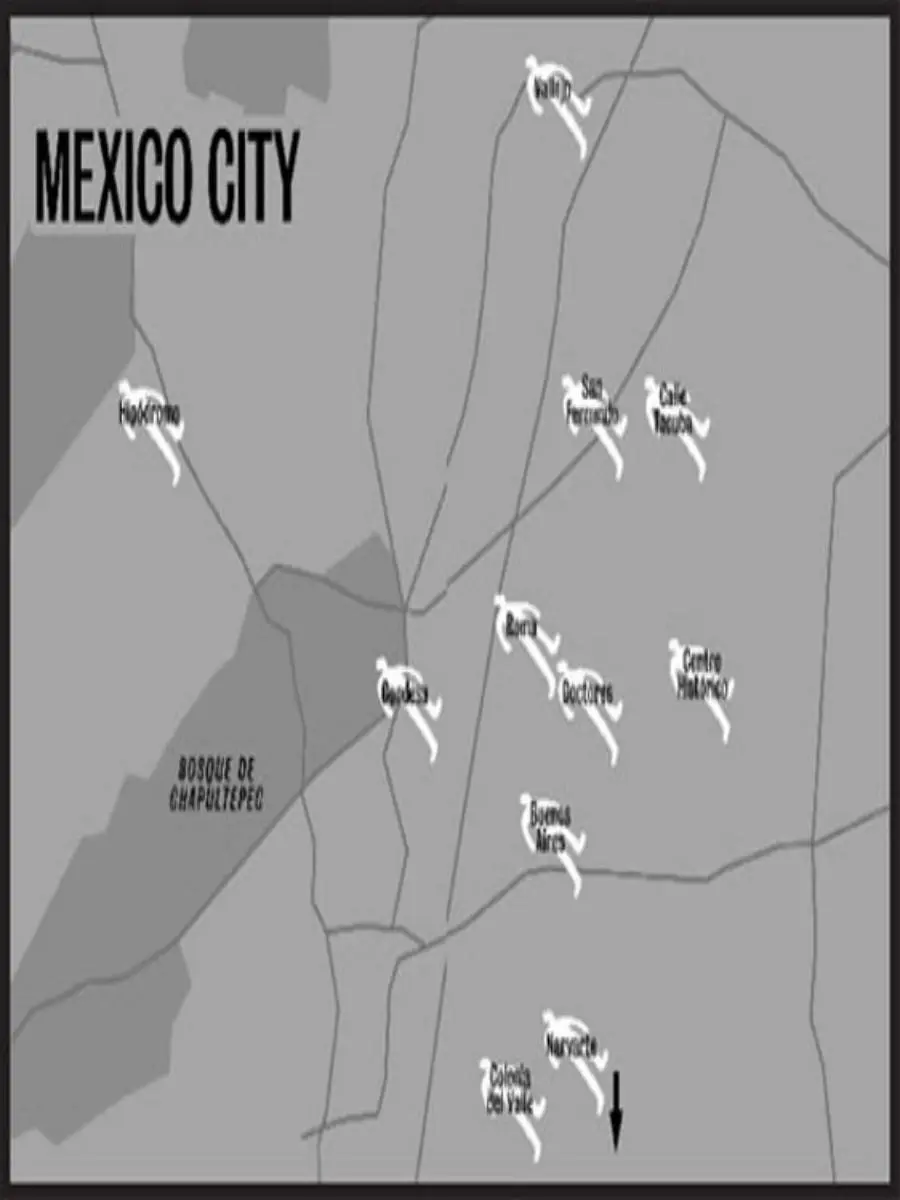

Twenty-one million residents in the metropolitan area. An infinite city, one of the biggest in the world, a fascinating blanket of lights for those arriving on planes; a huge Christmas tree on its side-red, green, yellow, white; mercury, tungsten, sodium, neon. A city gone crazy with pollution, rain, traffic; an economic crisis that’s been going on for twenty-five years.

A city famously notable for the strangest reasons: for being the urban counterpoint to the Chiapas jungle; for having the most diverse collection of jokes about death; for setting the record for most political protests in one year; for having two invisible volcanoes and the most corrupt police force on the planet.

Mexico is talked about more in jest than in earnest-how local law enforcement agents made martyrs of torturers in Argentina, how they bribed corrupt Thai cops, how they taught Colombian narcotraffickers to snort coke. But the rumors are miles behind reality. Here, a timid Snow White dictates the police report to Dr. Frankenstein.

To put memory in order, let us recall: in the early 1980s, the city’s chief of police, General Arturo Durazo Moreno, was in charge of chasing down a gang of killers associated with South American drug dealers who were found massacred in a blackwater collector in the city’s sewage system. The case provoked waves of newspaper ink, and the police suggested that it could have been a settling of scores between Central American gangs. A couple of years later the scandal resurfaced, and this time General Durazo was indicted. He was accused, among other things, of having given the order to kill rival Colombian dealers. The assassin, in that magical alchemy that is Mexican insanity, turned out to be his own prosecutor. His second-in-command, the chief of the state police, Francisco Sahagún Baca, was the head of the antidrug force, though he himself was one of the most notorious drug traffickers in the country.

The paradox: heaven’s door in Lucifer’s hands. Evil is everywhere. Each year, hundreds of police officers are fired, attempts are made to democratize Mexico City… but the cancer keeps metastasizing. Authority within the city depends on the police, no matter how corrupt they are. Now, in the name of modernity, everyone’s uncomfortable with this. They don’t know what to do. When the Division for the Investigation and Prevention of Delinquency was disbanded some twenty years ago, a spate of robberies inundated the Valley of Mexico. There were sixty-one assaults with a deadly weapon in a six-month period. The ex-cops turned a section of the city into their own turf. But it was just a small transition. As a matter of course, when they were still active officers, they had extorted, abused, robbed, and raped. Every now and then they went after some thief who operated outside of their jurisdiction. As ex-cops, they continued doing the same thing, perhaps pushing the envelope a little bit.

If you’re lucky, you can stay away from it, you can keep your distance… until, suddenly, without a clear explanation of how, you fall into the web and become trapped.

What are the unwritten rules? How can you avoid them?

Survey question: how many citizens do you know who, when assaulted on the street, will call the police? A few, none; maybe one of those boys in blue who patrols the intersections of this newly democratic city? A secret cop? Not on your life. What do you want, to be assaulted twice?

How big is the Mexico City police force? They say fifty-two squads. How many are officially sanctioned? How many bodyguards, paramilitary forces, armed groups associated with this or that official unit are there?

You wake up in the morning with the uneasy feeling that the law of probabilities is working against you.

You’re going to die, the guy tells the man on his knees, and he repeats the phrase, showing off the gun barrel. The kneeling man, who’s bleeding a bit from the bridge of his nose, doesn’t respond; he reflects that, yes, he’s going to die.

Hours later, when he tells his story to a pack of sleepy journalists, he thinks that, yes, he died, he died a little.

The man is Deputy Leonel Durán, member of the Party of the Democratic Revolution’s (PRD) National Council. Sometime in July 2007, a black car cut off his vehicle at an intersection. Using both a pistol and an automatic weapon, they made him get out; political threats got tangled up with the vulgar assault, they threw him in the trunk, beat him, stole his credit cards, drove all over Mexico City with him imprisoned back there; they took his watch.

In the end, they left him in an open field, after threatening to charge him with running away from the law.

One of his cards was overdrawn and was therefore swallowed by the bank machine. This infuriated the cops most of all.

Toward the end of the ’90s, a series of rapes that followed a certain pattern took place in the southern part of the city: a group of armed men would assault a young couple. First the robbery, then the rape. They usually stuffed the boyfriend in the trunk of a car. All the rapes were followed by death threats. Terror was practiced without reason-apparently, just to see what it felt like to wield the power of death itself. In a few cases, things got out of hand: a girl was strangled to death, an aggressive boyfriend was shot, another one asphyxiated in the trunk.

The majority of the rapes weren’t reported. That was traditional. But in one case, the victim was the daughter of an important political operative. There was a police investigation. Other young victims emerged and recognized their assailants in a police photo album.

In a photo album of known delinquents? No. It contained pictures of political operatives. The gang of rapists consisted mostly of members of Assistant Prosecutor Javier Coello Trejo’s bodyguard corps; he was deputy to the attorney general of the republic in charge of antidrug operations. The guys had too much free time sitting in parked cars, hanging out by building entrances, lounging at the homes of politicians. They had to pass the hours somehow…

Several of the killer rapists went to trial, others remained free. The assistant prosecutor was let go from his post and transferred to the Office of the Federal Prosecutor for the Consumer. There he could go after those who upped the price too much on video cassettes.

Can it be that the black cloud of pollution that runs in the

fast lane from the northeast to the southwest slowly drives us crazy?

Yet there’s something beyond madness here: discipline. In Santa Clara-the industrial zone in the city’s far north, a neighborhood full of chemical slush and loose dirt-a patrol car waits at dawn for the workers to emerge from the graveyard shift at the Del Valle juice factory. The laborers have once again each received a small allotment of canned juice from the company. It’s a miserable concession to union demands in a time of crisis. The cops stop them a few meters from the exit and steal half of what’s in each worker’s box. They stuff the cans in the backseat of the patrol car until it’s full and they leave, the engine in low gear.

Читать дальше