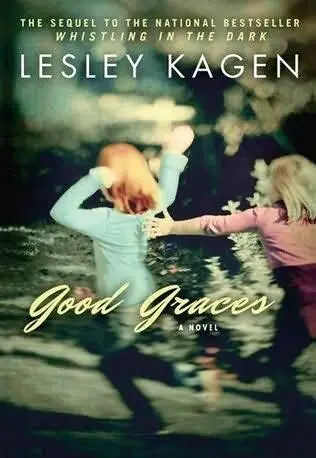

The second book in the Whistling in the Dark series, 2011

That summer earned itself a place in the record books that’s never been beat. The hardware store sold out of fans by mid-June and the Montgomery twins fainted at the Fourth of July parade. By the time August showed up, we couldn’t wait to send it packing.

To this day, my sister insists it was nothing more than the unrelenting heat that drove us to do what we did that summer, but that’s just Troo yanking my chain the way she always has. Deep down, she knows as well as I do that it wasn’t anything as mundane as the weather. It was the hand of the Almighty that shoved us off the straight-and-narrow path.

Whenever the old neighborhood pals get together, if it’s a particularly sticky evening, the way they all were back then, memories get tickled up. Sitting out on one of our back porches in the dwindling light, somebody will inevitably bring up the mysterious disappearance of one of our own that long-ago summer. Do you think he was murdered? What about kidnapping? He could have just taken off . Trying to figure out what happened to him has become as much fun for our friends as remembering our games of red light, green light and penny candy from the Five and Dime.

But for the O’Malley sisters, the fate of that certain someone is no more mysterious than the way he broke my front tooth that sultry August night. The two of us know exactly where that devil in the details has been for the past fifty years. He’s where we buried him the sweltering summer Troo was ten and I was eleven.

The summer of ’60.

Somebody at his funeral called Donny O’Malley lush . I couldn’t agree more. Daddy was just-picked corn on the cob and a game-saving double play all rolled into one, that’s how lush he was.

Someone else at the cemetery said that time heals all wounds. I don’t know about that.

Daddy crashed on his way home from a baseball game at Milwaukee County Stadium three years ago. The steering wheel went into his chest. I wasn’t in the car that afternoon. I hadn’t weeded my garden so he told me I had to stay back on the farm and I told him I hated him and wished for a different daddy. I didn’t mean it. I’d just been so looking forward to singing The Land of the Free and the Home of the Braves . Eating salty peanuts and the seventhinning stretch.

When he was in the hospital, Daddy shooed everyone else out of the room and had me lie down with him. “No matter what, you must take care of Troo,” he told me. “Keep her safe. You need to promise me that.” He had tubes coming out of him and there was a ping ping ing noise that reminded me of the 20, 000 Leagues Under the Sea movie. “Tell your sister the crash wasn’t her fault. And… tell your mother that I forgive her. I’ll be watching, Sally. Remember… things can happen when you least expect them… you… you always gotta be prepared. Pay attention to the details. The devil is in the details.”

I never forget what he told me or what I promised him, but Daddy is especially on my mind this morning. When it’s baseball season, I always remember him better. The other reason I’m thinking about him is because Troo and me just got home from getting our brand-new start-of-the-summer sneakers at Shuster’s Shoes on North Avenue. That’s the store where Hall Gustafson used to work. He’s the man Mother got married to real quick after Daddy died. My sister thinks she accepted his proposal because Hall had a tattoo on his arm that said Mother , but I think she did it because Daddy forgot to leave us a nest egg. I watched Mother collapse in our cornfield and beat the dirt with her fists, shouting, “Donny! How could you?” but I forgave him right off. When you’re a farmer, it’s hard to put something away for a rainy day.

The whole time we were trying on Keds this morning, I kept imagining that slobbering Swede stumbling out from behind the curtain where the shoes are hidden, but that was dumb. Our stepfather doesn’t have a job at Shuster’s or anyplace else anymore because he got into a fight at Jerbak’s Beer ’n Bowl with the owner, who was famous around here for bowling a 300 game but also for being quick with his fists. Hall’s in the Big House now. For murdering Mr. Jerbak with a bottle of Old Milwaukee. Sometimes in bed at night when I can’t sleep, which is mostly all the time, I think about how good that all worked out and just for a little while it makes me feel like God might know what He’s doing. At least part of the time. He did a bad job letting Daddy die, but I admire how the Almighty got rid of Mr. Jerbak and Hall in one fell swoop. That really was killing two dirty birds with one stone.

Troo wasn’t thinking about Hall when we were up at the store. Not how he dragged her out of bed and knocked her head against the wall or any of the other rotten stuff he did like sneaking behind Mother’s back with a floozy. My sister was having the best time this morning. She’s nuts about Shuster’s because it’s so modern. They’ve got a Foot-O-Scope machine that’s like an X-ray. Troo adores pressing her eyes to the black viewer to see inside her feet, but when I look down at my bones, they remind me of Daddy lying beneath the cemetery dirt.

“Ya know what I been thinkin’, Sal?” my sister asks.

We’re sitting on the back steps of the house. I’m raring to go, but she’s working hard to loop her new shoelaces into bunny ears. Troo was in the crash with Daddy. She played peek-a-boo with him on the way home from the baseball game. Holding her hands over his eyes for longer than she shoulda is what caused the car to go skidding out of control and smash into the old oak tree on Holly Road. She got her arm fractured. It aches before it’s going to rain and also made her not very good at tying.

“What?” I ask her.

“It would be a fantastic idea for us to get away from the neighborhood for a while. We should go away to camp this summer,” she says, batting her morning-sky blue eyes at me.

My eyes are green and I don’t have hair the color of maple leaves in the fall the way Troo does. I have thick blond hair that my mother brushes too hard and puts into a fat braid that goes down my back and deep dimples that I’ve been told more than a few times are very darling. I’ve always had long legs, but this past year they grew three and a half inches. My sister thinks I look like a yellow flamingo.

“We need to expand our horizons,” Troo says.

Even though we don’t look very much alike, we are what people call Irish twins. Troo will turn eleven two months before I turn twelve. I always know what she is really thinking and feeling. We have mental telepathy. So that’s how come I know my sister isn’t telling me the truth about why she wants to go to camp. It’s not the neighborhood she wants to get away from. She likes living in the brick house with the fat-leafed ivy growing up the sides and bright red geraniums in the window boxes and lilacs falling over the picket fence like a purple waterfall. It’s the owner of the house Troo’s got problems with. She wants to get away from Dave Rasmussen, who we moved in with at the end of last summer. He is my real father because when Daddy was in the war Mother accidentally had some of the sex with Dave.

For the longest time, I didn’t know that Dave was my flesh and blood. When I found out, I didn’t think I would get over it, but I mostly have, in my mind anyway. In my heart, Daddy is still my daddy and Dave is Dave. Maybe someday that will change for me, but it never will for my sister. Daddy will always be her one and only. He looked at her like she was a slice of banana cream pie. I was his second-favorite, plain old dependable cherry, and that was fine with me. When you got a sister like Troo, you gotta expect these things.

Читать дальше