‘None but Seamus will be stirrin’, poor divil. He’s th’ butler at Catharmore-always up at th’ crack, cooking, polishing, laying fires. God above, th’ man’s a saint.’

‘Fires in August-that’s usual?’

‘We keep a bit of fire burnin’ year-round, th’ Conors.’

They were having a shout over the rattle which filled the Rover from front to rear; the scent of last night’s rain poured through the open windows.

‘We’ll do a quick shot around the drive, then be off.’

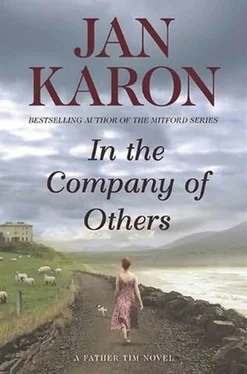

The road was steep, rutted, strewn in places by blossoms of wild fuchsia loosed by the downpour. Fallen trees decayed among brambles at the wood’s edge.

‘Most of the house is on th’ ruin-still an’ all, it looks out to one of the finest prospects in th’ west of Ireland.’

They rounded a curve overhung by rhododendron. The house appeared on a treeless prominence, engraved against a billow of clouds.

He was unaccustomed to limestone houses. In his rustic view, limestone was the material of stoical municipal buildings with their crust of soot and pigeon droppings.

‘The Conor cabin,’ Liam said, ironic.

He sensed that he was to think Catharmore handsome. He did not.

‘Built by an Irishman in the early 1860s, name of O’Donnell. Thanks to a rich uncle, O’Donnell emigrated to Philadelphia as a lad-medical school, a successful practice, everything a Sligo boy could dream of. Came home to Lough Arrow with his wife in 1859. The hunger years had put th’ passion in him for helpin’ th’ poor at home.’

‘The lintels, the keystones-very striking,’ he said. His mother and Peggy had raised him to look for the positive in every common thing. ‘A splendid portico.’ It was the best he could do.

‘Father bought it when he was fifty-two; moved out from Sligo, where he owned a sizable building operation. Came with an invalid wife who was after havin’ th’ country air. Then his wife died, and he married her nursemaid.’

Liam braked for the view down the slope.

At the foot of the hill, the blade of blue water, slicing through green; the clouds-cumulus, immense, on the move. He instinctively crossed himself. ‘Glorious,’ he said, genuinely touched. ‘A privilege to see it.’

‘The red roof showin’ among the trees, that’s us at Broughadoon. The specks on the water might be our lads. I put our order in for five bric and a nice pike-this afternoon, there’ll be four American women on us.’

‘Whoa.’

‘A book club, they told Anna, that turned off to a poker club.’

They laughed.

‘But lately ’t is a travel club.’

‘Flexibility, that’s the ticket.’

The Rover rattled along the grass circle at the front of the house.

‘The nursemaid was my mother, Evelyn McGuiness. Twenty-some years of age and a ravin’ beauty, they say; one of seven raised in a one-room cabin a few kilometers from here. Fierce an’ ravishing, my father called her. Th’ lord of th’ manor made a mighty case for himself, but she says ‘t was th’ fine Irish house she married.’

Five bays. Windows on the second and third floors blind with interior shutters, as if hiding the rooms from bird and hawk; vines protruding from copper guttering. As they approached the portico, three Labs raced down the steps.

‘That’s Roddy th’ yellow, Kevin th’ chocolate-you met them at th’ lodge-and the oul’ black fellow’s Cuchulain.’ Liam braked and dug biscuits from the pocket of his wind-breaker. ‘Show y’r manners, ye lazy cods. Ah, Cuch, ye’re a good by, yes ye are. Roddy, ye’re latherin’ up m’ arm, get a grip on y’rself.’ He flung a handful of biscuits across the grass. ‘Run for it, lads, ye’re too fat altogether.

‘There was a garden wall ten feet high,’ Liam said as they drove down the hill. ‘My brother, Paddy, pulled it down. He can have the place and all th’ nuisance of it. I’m happy with my books and my Barret.’

‘There’s a senior Barret and a junior, I believe. ’ He had read a little about Irish art; the senior was definitely the bigger ticket.

‘This is th’ senior. Paddy’s after me to sell it, or give it to Trinity College-as if he ever gave two quid to th’ place.’

‘You’re a Trinity man?’

‘Read Latin and botany at Trinity. Barely half a year was all I could take of it. Too confinin’. When Father died at th’ middle of term, I made off for Lough Arrow an’ never looked back. Truth is, I grew up wild as bog cotton; took my degree in th’ woods and fields.’

He’d taken a degree of his own in the woods and fields. The sweltering summers of his Mississippi youth had been his favored university.

‘I learned off a few poems as a lad, but a bit of something by Synge is all that comes to mind these days-I knew the stars, the flowers and the birds, the grey and wintry sides of many glens, and did but half remember human words, in converse with the mountains, moors and fens.

‘I excused myself from bein’ raised, you might say. I liked bein’ in th’ open, studying flowers and weeds and bushes and bugs. I was brought up by th’ people, really-snagged hares, took ’em to a cottage door for my supper. Was wild as a hare myself-a wonderful childhood. The upbringin’ I lacked from my mother, I got from twenty others. I never felt so happy as when sittin’ by the open fire of a cottage, listenin’ to a story or a fiddle or talkin’ to the old people about home cures. Ah, they’d go on about pus and gangrene and bile and deformities of all kinds- people risin’ up from their coffins at a wake, birthin’ infants with two heads. Fascinating.

‘I like to think I wasn’t a completely bad fellow, for all that. Didn’t drown any cats or cut th’ tails off dogs, though I did scare th’ daylights out of a teacher I tangled with more than once. I pulled a bedsheet over m’self when she was walkin’ home at dark, jumped out of th’ hedge, and yelled at th’ top of m’ voice, May th’ divil put warts on y’r oul’ nose! She was easier on me after that, and I was easier with her-’t was an unspoken pact we had; I think she knew who was under the sheet.

‘But see here?’ Liam tapped the right side of his nose. ‘A wart. Came there some time later, but made me wonder, nonetheless.’

They laughed, comfortable.

‘Is primogeniture still practiced here?’

‘Outlawed in the sixties. Ever since he was a kid, Paddy was fierce to have th’ house. When Father died, there was no chance of Mother sellin’ th’ place, though God knows, there was hardly two bob left to maintain it-he was eighty-some when he passed.

‘I did my bit to help-worked as a finish carpenter around th’ villages and townlands; at weekends, came home and tried to keep th’ place standing. Paddy had graduated Trinity a few years before, joined forces with an ad agency in Dublin and tricked himself out as an art director. Our mother was proud enough-though she was after havin’ a doctor in th’ family. Then off to London Paddy went, where he became somethin’ of a star in the ad business.

‘He lived in London a few years, married twice, divorced twice, made a name for himself. Then off to New York an’ puts together his own outfit an’ marries again. ’t was a smash, th’ business, but a bust, th’ marriage.

‘When he came home a few years back, he’d just sold his company to some Madison Avenue bucko. He was what any man in Sligo would call rich-but here’s where th’ cheese gets bindin’. ’t was his dream to turn Catharmore into a country house hotel. ’t is th’ fashion, you know, turning our country houses into hotels.’

‘Helps keep the roof over your head.’

‘Th’ place had run down altogether; we thought he’d gone simple.’

Читать дальше