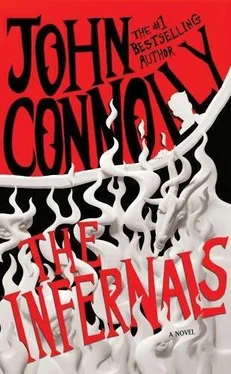

John Connolly - The Infernals aka Hell's Bells

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «John Connolly - The Infernals aka Hell's Bells» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Infernals aka Hell's Bells

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Infernals aka Hell's Bells: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Infernals aka Hell's Bells»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Infernals aka Hell's Bells — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Infernals aka Hell's Bells», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

And each time her eyes were filled with a blue light, and they burned with her hatred for Samuel.

Samuel’s mother greeted him from the kitchen as he opened the front door and dumped his bag in the hall.

“Hello, Samuel. Did you have a good day?”

“If, by good, you mean embarrassing and soul-destroying, then, yes, I had a good day,” said Samuel.

“Oh dear,” said his mum. “Sit down at the table and I’ll make you a nice cup of tea.”

What was it about mothers, wondered Samuel, that led them to believe all of the problems of the world could be solved with a nice cup of tea? Samuel could have walked in with his head under his arm, blood spurting from his neck and his back quilled with arrows, and his mother would have suggested a nice cup of tea as a means of salving his wounds. She would probably even have tried to rub some tea on his severed head in an effort to stick it back on his shoulders.

But the funny thing was that, more often than not, a cup of tea and a consoling word from your mum were enough to make things at least a little better, so Samuel sat down and waited until a steaming mug of tea was placed in front of him. It really did smell good. He could almost feel it warming his throat already. Today had been bad, but perhaps tomorrow would be better. Tea: our friend in times of trouble.

“Oh bother,” said Samuel’s mother. “We’re out of milk.”

Samuel’s forehead thumped hard against the kitchen table.

“I’ll go,” he said.

“There’s a good lad,” said his mum. “I’ll have a fresh cup waiting for you when you get back. Will you get some bread while you’re at it? I don’t know: even with your dad gone, we’re still getting through as much food as ever.”

Samuel winced. He didn’t know which hurt more: to hear his mother grow sad when she talked about his dad’s absence, or to hear her remark upon it so casually. His mother seemed to notice his discomfort, for she moved to him and enveloped him in her arms.

“Oh, you,” she said, kissing his hair. “I don’t mind you eating. You’re a growing lad. And your dad and I, well, we’re talking, which is something. I’m not as angry with him as I was, although I’d still hit him over the head with a frying pan given half the chance. But we’re okay, you and I, aren’t we?”

Samuel nodded, his eyes closed, taking in the comforting smell of flour and perfume from his mother’s dress.

“Yes, we’re okay,” he said, although he wasn’t sure if it was true.

His mother pushed him gently away, and held him at arm’s length. She looked at him seriously.

“There’s been no more, um, strangeness, has there?” she asked.

“You mean demons?”

Now it was his mother’s turn to look uncomfortable.

“Yes, if that’s what you want to call them.”

“That’s what they were.”

“Now, I don’t want to get into an argument about it,” said his mum. “I’m only asking.”

“No, Mum,” said Samuel. “There’s been no more strangeness.” Not unless you include glimpses of a woman with her face stitched together, staring out at him from mirrors and glass doors. “There’s been no more strangeness at all.”

VII

BEFORE WE GO ANY further, a quick word about evil.

Evil has been in existence for a very long time, long enough to be part of the birth of everything billions and billions of years ago following the Big Bang that brought this universe into being. Unfortunately, for a while after the Big Bang there wasn’t much for Evil to do because there wasn’t a great deal of life about, and what life there was consisted of little single-celled organisms which had quite enough to be getting along with just trying to become multicelled organisms, thank you very much, without having to worry about being unkind to one another for no good reason as well. Even when these multicelled organisms grew incredibly complex, and became sharks, and spiders, and carnivorous dinosaurs, they still didn’t provide much amusement for Evil. These beasts operated on instinct alone, and their instinct was simply to eat, and thus to survive.

But then man came along, and Evil perked up a bit, because here was a creature that could choose, which made it very interesting indeed. Being good or bad is not a passive state: you have to decide to be one or the other. Evil did everything it could to encourage people to do bad instead of good, and because it was clever it disguised itself well, so that people who did bad things found ways to convince themselves that they weren’t really bad at all. They needed more money to be happy, and hence they stole, or they cheated on their taxes; and then they told lies to hide what they’d done, because they were kind of sorry for it, but not sorry enough to admit what they’d done, or to stop doing it. In the end, most of it came down to selfishness, but Evil didn’t mind. You could call it what you wanted, as far as Evil was concerned, just as long as you kept on being bad.

And Evil wasn’t just busy in this universe, but in a lot of others too, for ours was but one in a great froth of universes known as the Multiverse, each one its own expanding bubble of planets and stars. You might think that this would require Evil to spread itself a little thinly, because there can only be so much Evil to go around, but you’d be surprised what Evil can do when it puts its mind to it. On the other hand, no matter how hard Evil tries, it can never quite match up to the power of Good, because Evil is ultimately self-destructive. Evil may set out to corrupt others, but in the process it corrupts itself. That’s just the way Evil is. All things considered, it’s better to be on the side of Good, even if Evil occasionally has nicer uniforms.

• • •

Mrs. Abernathy, who was very evil indeed, sat in a high chamber in her palace, a terrifying constuct of spars and sharp edges carved from a single massive slab of shiny black volcanic rock, and stared intently at the shard of glass before her. She had “borrowed” it a long, long time before from the Great Malevolence, for he had many such shards, and she had convinced herself that one more or less would make no difference to him. They were his windows into the world of men, each revealing to him some facet of the existence that he hated, yet also, in the pit of his being, secretly craved. He would watch the sun set, and lakes turn to gold. He would see children grow up to have children of their own, and become old among those whom they loved, and who loved them in turn. He would gaze upon husbands and wives, brothers and sisters, upon puppies, and frogs, and elephants. He would even gaze upon goldfish in bowls, and hamsters who ran around inside wheels to distract themselves from their tiny cages, and flies struggling in the webs of spiders, and he would envy each and every living thing its freedom, even if it was only the freedom to die.

For so long, Mrs. Abernathy had shared her master’s desire to turn the Earth into a version of Hell, but something had changed. What that something was might be guessed from the fact that the windows of her dreadful lair, which, in its way, had long been nearly as awful as the Great Malevolence’s Mountain of Despair, but considerably smaller, and with better views, had been decorated with net curtains. The curtains were black and, upon closer inspection, seemed to have been used at some point to catch horrible mutated fish, as the remains of a few were still caught in their strands, but at least someone was making an effort. A long table constructed entirely of tombstones now had a yellow vase at its center, a vase, furthermore, that bore a pattern of dozing cats. Admittedly, the vase was filled with ugly bloodred flowers that hid sharp teeth inside their petals, and those teeth would have made short work of any real cats that made the mistake of falling asleep within snapping distance, but it was a start, just like the curtains, and the doormat that read “Please Wipe Your Cloven Hooves!,” and the jar of potpourri made from the husks of poisonous beetles and scented with stagnant water.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Infernals aka Hell's Bells»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Infernals aka Hell's Bells» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Infernals aka Hell's Bells» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.