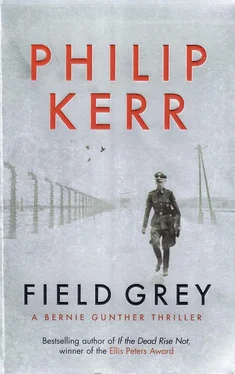

Philip Kerr - Field Grey

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philip Kerr - Field Grey» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Field Grey

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Field Grey: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Field Grey»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Field Grey — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Field Grey», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

At considerable length M. Boessel du Bourg read the verdict and then delivered the sentence, which was death, of course. This was the cue for lots of people in court to begin shouting at the two defendants and, a little to my surprise, I found I was almost sorry for them. Once the two most powerful men in Paris, they now looked like two architects receiving the news that they hadn't won an important contract. Oberg blinked with disbelief. Knochen let out a loud sigh of disappointment. And amid more abuse and cheers from all around me the two Germans were led out of court. One of my SDECE escorts leaned towards me and said:

'Of course, they will appeal the sentences.'

'Still, I do get the point,' I said. 'I am encouraged by Voltaire's example.'

'You've read Voltaire?'

'Not as such, no. But I'd like to. Especially when one considers the alternative.'

'Which is?'

'It's hard to read anything when your head is lying in a basket,' I said.

'All Germans like Voltaire, yes? Frederick the Great was a great friend of Voltaire, yes?'

'I think he was. At first.'

'Germans and French should be friends now.'

'Yes. Indeed. The Schuman Plan. Exactly.'

'For this reason, I mean for the sake of Franco-German relations, I think the appeal will be successful.'

'That's good news,' I said, although I could hardly have cared less about Knochen's fate. All the same I was surprised at this conversational turn of events, and I spent the drive back to the Swimming Pool feeling encouraged. Perhaps my prospects were improving after all. Despite the trial of Oberg and Knochen, and the verdict, there was perhaps good reason to imagine that the SDECE was keener on cooperation than coercion, and this suited me very well.

From the Cherche-Midi we drove east to the outskirts of Paris. The Caserne Mortier in the barracks of the Tourelles was a traditional-looking set of buildings near the Boulevard Mortier in the twentieth arrondissement. Made of red brick and semi- rusticated sandstone, the C.M. held no obvious affinity with a swimming pool beyond an echo in the corridors and an Olympic-sized courtyard which, when it rained, resembled an enormous pool of black water.

My interrogators were quiet-spoken but muscular. They wore plain clothes and did not give me their names. No more did they accuse me of anything. To my relief they weren't much interested in the events that had happened on the road to Lourdes in the summer of 1940. There were two of them. They had intense, birdlike faces, five o'clock shadows that appeared just after lunch, damp shirt collars, nicotine-stained fingers and espresso breath. They were cops or something very like it. One of the men, the heavier smoker, had very white hair and very black eyebrows that looked like two lost caterpillars. The other was taller, with a whore's sulky mouth, ears like the handles on a trophy, and an insomniac's hooded, heavy eyes. The insomniac spoke quite good German but mostly we spoke in English, and when that failed I took a shot at French and sometimes managed to hit what I was aiming at. But it was more of a conversation than an interrogation and, save for the holsters on their broad shoulders, we could have been three guys in a bar in Montmartre.

'Did you have much to do with the Carlingue?'

'The Carlingue? What's that?'

'The French Gestapo. They worked out of Rue Lauriston. Number ninety-three. Did you ever go there?'

'That must have been after my time.'

'They were criminals recruited by Knochen, mostly from the Fresnes prison,' said Eyebrows. 'Armenians, Muslims, North Africans, mostly.'

I smiled. This, or something like it, was what the French always said when they didn't want to admit that almost as many Frenchmen as Germans had been Nazis. And given their postwar record in Vietnam and Algeria it was tempting to see them as even more racist than we were in Germany. After all, no one had forced them to deport French Jews – including Dreyfus's own grand-daughter – to the death camps of Auschwitz and Treblinka. Naturally, I hardly wanted to hurt anyone's feelings by saying so directly, but as the subject remained on the table, I shrugged and said:

'I knew some French policemen. The ones I've already told you about. But not any French Gestapo. Now the French SS, that's something else again. But none of them were Muslims. As I recall they were nearly all Catholics.'

'Did you know many, from the SS Charlemagne Division?'

'A few.'

'Let's talk about the ones you did know.'

'All right. Mostly they were Frenchmen captured by the Russians during the battle for Berlin, in 1945. They were men in the POW camps, like I was. The Russians treated them the same way they treated us Germans. Badly. We were all fascists in their book. But really there was only one Frenchman in the camps I got to know well enough to call him a comrade.'

'What was his name?'

'Edgard,' I said. 'Edgard de something or other.'

'Try to remember,' one of the Frenchmen said patiently.

'Boudin?' I shrugged. 'De Boudin? I don't know. It was a long time ago. A lifetime. Not a good lifetime, either. Some of those poor bastards are only just coming home now.'

'It couldn't have been de Boudin. Boudin means sausage, or pudding. That couldn't have been his name.' He paused. 'Try to think.'

I thought for a moment and then shrugged. 'Sorry.'

'Maybe if you told us something of what you can remember of him, the name will come back to you,' suggested the other Frenchman. He uncorked a bottle of red wine, poured a little into a small round glass and then sniffed it carefully before tasting it and pouring some more for me and the two of them. In that room, on that dull summer's day, this small ritual made me feel civilised again, as if, after months of incarceration and abuse, I amounted to something more than just a name chalked on a little board by a cell door.

I toasted his courtesy, drank some wine, and said, 'I first met him here in Paris, in 1940. I think it must have been Herbert Hagen who introduced us. Something to do with the policy on Jews in Paris, I don't know. I never really cared about that sort of thing. Well, we all say that now, don't we? The Germans. Anyway, Edgard de something or other was almost as anti-Semitic as Hagen if such a thing was possible, but in spite of that, I quite liked him. He had been a captain in the Great War, after which he'd failed in civvy street, and this had led him to join the French Foreign Legion. I think he was stationed in Morocco before being sent to Indo-China. And of course he hated the communists, so that was all right. We had that much in common, anyway.

'Well, that was 1940, and when I left Paris I didn't expect to see him again, and certainly never as soon as November 1941 in the Ukraine. Edgard was part of this French unit in the German army – not the SS, that was later – but the Legion of French Volunteers against Bolshevism, or some such nonsense. That's what the French called it. I think we just called it the something infantry. The 638th. Yes. That was it. Mostly the men were fascists of Vichy French or even French POWs who didn't fancy being sent to Germany as forced labour with the Todt organisation. There were probably about six thousand of them. Poor bastards.'

'Why do you say that?'

I sipped some wine and helped myself to a cigarette from the packet on the table. Outside the window, in the central courtyard, someone was trying to start a motor car without success; somewhere further away, de Gaulle was waiting or sulking, depending on how you looked at it; and the French Army was licking its wounds after getting its ass kicked – again – in Vietnam.

'Because they couldn't have known what they were letting themselves in for,' I said. 'Fighting partisans sounds fair enough back here in Paris, but out there in Byelorussia it meant something very different.' I shook my head sadly. 'There was no honour in it. No glory. Not what they were looking for anyway.'

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Field Grey»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Field Grey» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Field Grey» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.