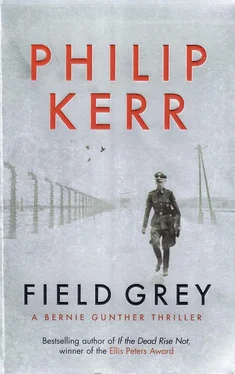

Philip Kerr - Field Grey

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Philip Kerr - Field Grey» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Field Grey

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Field Grey: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Field Grey»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Field Grey — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Field Grey», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Bomelburg wagged his finger at me. 'You're just doing your job, old fellow. But I know this case better than anyone. Before I joined the Gestapo I was with our foreign service in Paris and I spent three months working on this case. For one thing, Poland is now a part of the Greater German Reich. As is France. And for another the murder took place in the German embassy, here in Paris. Technically, diplomatically, that was German soil. And that makes a big difference.'

'Yes, of course,' I said, meekly. 'That does make a big difference.'

Certainly it had made a big difference to Germany's Jews. Herschel Grynszpan's murder of a junior official in the Paris embassy in November 1938 had been used as an excuse by the Nazis to launch a massive pogrom at home. Until the night of November 10th, 1938 – Kristallnacht – it was almost possible to imagine that I still lived in a civilised country. The trial was certain to be the kind the Nazis liked: a show trial, with the verdict a foregone conclusion; but – if Bomelburg was being honest – at least Grynszpan wasn't about to be murdered by the roadside.

Leaving Kestner, Matignon and Savigny to go to the Prison St Michel in Toulouse, Bomelburg and I, accompanied by six SS men, set off on the sixty-five-kilometre drive south to Le Vernet. Frau Kemmerich did not come with us as it seemed her husband was after all in another French concentration camp at Moisdon-la-Riviere, in Brittany.

Le Vernet was near Pamiers and the camp was a short way south of the local railway station, which Bomelburg described as 'convenient'. There was a cemetery to the north of the camp but he neglected to mention if that was convenient too, although I was sure it would be: Le Vernet was even worse than Gurs. Surrounded by miles of barbed wire in an otherwise deserted patch of French countryside, the many huts looked like coffins laid out after some giant's battle. They were in a deplorable state, as were the two thousand men who were imprisoned there, many of them emaciated and guarded by well-fed French gendarmes. The prisoners laboured to build an inadequate road between the railway station and the cemetery. There were four roll-calls a day, each of them lasting half an hour. We arrived just before the third, explained our mission to the French policeman in charge, and he handed us politely over to the care of a vile-looking officer who smelt strongly of aniseed, and his yellow-faced Corsican sergeant. They listened as Oltramare translated the details of our mission. Monsieur Aniseed nodded and led the way into the camp.

Bomelburg and I followed, pistols in hand, as we had been warned that the men of Hut Thirty-Two, the 'Leper Barrack' were considered the most dangerous in Camp Le Vernet. Oltramare followed at a distance, also armed. And the three of us waited outside while several French gendarmes entered the pitch-black barrack and drove the occupants outside with whips and curses.

These men were in a disgraceful condition – worse than at Gurs, and even worse than Dachau. Their ankles were swollen and their bellies distended from starvation. They wore cheap- looking galoshes on their feet and the same ragged clothing they'd probably been wearing since the winter of 1937 when they had fled the advance of Franco's Nationalist army. Some of them were half-naked. They were all infested with vermin. They knew what was coming but were too beaten to sing the Internationale in defiance of our presence.

It took several minutes for the barrack to empty and the men to line up again. Just as you thought the barrack couldn't contain any more men, others came out until there were three hundred and fifty of them paraded in front of us. The judgement line from Purgatory to Hell could not have looked more abject. And with every second I was confronted with their gaunt, unshaven faces the more I wanted to shoot Monsieur Aniseed and his fat gendarmes.

While the Corsican called the roll, Bomelburg checked his clipboard looking for names that tallied; and while they did that I walked between their ranks, like the Kaiser come to hand out a few Iron Crosses to the bravest of the brave, looking to see if I could pick out a man I hadn't seen for nine years. But I never saw him there; and I never heard his name called out. Not that I put much faith in a name. From everything I'd read about him in Heydrich's file, Erich Mielke was too smart to have been arrested and interned using his real name. Bomelburg knew this, of course. But there were others who had not been possessed of the same presence of mind as the German Comintern agent; and as these few men were identified they were led away to the Administration Barracks by the gendarmes.

'He's not in this barrack,' I said, finally.

'The adjutant says there's another all-German barrack in this section,' said Oltramare. 'This one is all International Brigade and it would make sense for Mielke to keep away from them, especially now that Stalin has closed his doors to them.'

The men from Barrack Thirty-Two were driven back inside and we repeated the whole exercise with the men from Barrack Thirty-Three. According to the yellow-faced Corsican – he looked like a careless tanner – these were all communists who had fled from Hitler's Germany only to find themselves interned as undesirable aliens when war was declared in September 1939. Consequently these men were in rather better shape than their comrades from the International Brigades. That wouldn't have been difficult.

Once again I walked up and down the lines of prisoners while Bomelburg and the Corsican called the roll. These faces were more defiant than the others and most of the men met my eye with unshifting hatred. Some were Jews, I thought. Others were more obviously Aryan. Once or twice I paused and stared levelly at a man, but I never identified any of the prisoners as Erich Mielke.

Not even when I recognised him.

As the Corsican finished the roll-call I walked back to Bomelburg's side, shaking my head.

'No luck?'

'No. He's not there.'

'Are you sure? Some of these fellows are a shadow of their former selves. Six months in this place and I doubt my own wife would recognise me. Have another look, Captain.'

'All right, sir.'

And while I looked at the prisoners again, I made an announcement, for the sake of impressing Bomelburg.

'Listen,' I said. 'We're looking for a man called Erich Fritz Emil Mielke. Perhaps you know him by a different name. I don't care about his politics, he's wanted for the murders of two Berlin policemen in 1931. I'm sure many of you read about it in the newspapers at the time. This man is thirty-three years old, fair-haired, medium height, brown eyes, Protestant, from Berlin. He attended the Kolnisches Gymnasium. Probably speaks Russian quite well, and a bit of Spanish. Maybe he's good with his hands. His father is a woodworker.'

All the time I was speaking I could feel Mielke looking at me, knowing I'd recognised him the way he'd recognised me and doubtless wondering why I didn't arrest him straight away and what the Hell was going on. I holstered my pistol and took off my officer's cap in the hope I might look a little less like a Nazi.

'Gentlemen, I make you this promise. If any one of you identifies Erich Mielke to me now, I will personally speak to the camp commander with a view to organising your release as soon as possible.'

It was the kind of promise that a Nazi would have made. A shifting promise that no one would have trusted. I hoped so. Because after what had happened to the prisoners from Gurs in the forest near Lourdes, the last thing I wanted to do was help the Nazis arrest any more Germans, even a German who had murdered two policemen. I couldn't do anything about the other men who were on Bomelburg's list, but I was damned if I was going to finger any more Germans for Heydrich. Not now.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Field Grey»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Field Grey» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Field Grey» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.