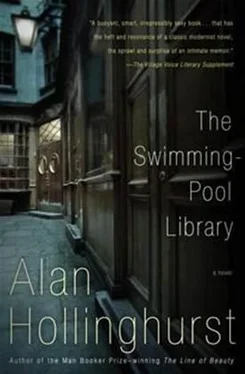

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

Strong I remember first in the bidets, in my first week in College (it might even have been my first day). In spite of everything to the contrary in the domineering, exalted ethos of the school, the bidets startled me from the beginning by their democratic nature-boys of all ages bathing in the same room, knees drawn up in the shallow tin baths. We’d had nothing like it at Mr. Tootel’s. I recall how Strong, whose figure was pretty well though not excessively attuned to his name, stood up dripping & came and stood beside me. I was not used to taking my clothes off in public: I hung back with my hands clasped in front of me rather than climb into the scummy water out of which this prefect had just arisen. There was something repugnant to me in the water: it was one of the many moments when the sweet, civilised certainties of home were trampled by the stronger, medieval laws of school. ‘Get in, baby,’ said Strong with a sceptical look, drying himself brusquely. Still I hesitated, and I think I was only able to do it because I felt suddenly unaware of myself in the senior boy’s presence. Certainly it never struck me that I could be seen in a sexual light myself. I looked at Strong, and at his red, thick prick, which was thickly overgrown with black hair, as were his legs, all matted & streaked down with the bathwater. I had never been in the proximity of a mature boy before. I suppose I must have stared rather obviously-not out of lust but interest. I think, though I cannot be sure, that Strong took this as a kind of sign, and perhaps he was aware of the spell he had cast. I was not aware of it myself, only now I see that it was the first time that something happened that wd recur with me-a kind of loss of selfconsciousness in the aura of a more beautiful or desired person. My eyes were entranced, & devoured what was before them. In retrospect I think I see the selfconscious way Strong finally wrapped his towel round his waist and called out boisterously to another prefect, ‘Bloody new men!’ I felt a thrill of mastered shock at his language.

After that I always got straight in the water: that too was because I had passed through some kind of initiation. I knew that one day I should leave the water for other men younger than myself. I remember how the little islets of scum used to float between one’s legs & hang around one’s kit.

I was made to learn my notions, never imagining that they were useless to anyone older than the prefects who tested us on them. I memorised them religiously, & will never forget them, I suppose. My pleasure when challenged for the colours of Chawker’s hatband and came out with the symmetrical ‘plum-straw-plum-light-blue-plum-straw-plum’ was so obvious that the prefect, Stanbridge, tweaked my ears, & made me falter, though not fatally, in reciting the Seven Birthplaces of Homer.

What I was much slower to learn were the notions that weren’t written down, the notions people got into their heads. It wasn’t long before Stanbridge and other, less senior men in the dormitory, started brocking me. ‘Oh, he’s quite a little tweake, isn’t he?’ Stanbridge would say sarcastically, sitting on my bed & patting me with a hand whose gentleness was suddenly disguised with mocking roughness. I was frightened in the near dark. I didn’t know what a tweake was-all I could think of was how Stanbridge tweaked my ears. There was a suppressed excitement in the other men, who gathered around, taking their lead from Stanbridge, emboldened to knowing sarcasm by their numbers. ‘You are a tweake, aren’t you, Nantwich?’ said Morgan, a fat, ugly, Welsh quirister, reviled by the others but being allowed, too, into the menacing conspiracy around me. ‘Tell us the truth.’ He spoke in a false, loving way, stroking my hair. The truth of the matter was I did not know what was going on, but my heart knocked in my breast and I felt sick. I longed for the morning-chapel, & being in my toys again, especially for the discipline and concealment of chapel and books.

This torture, which was mental more than physical, went on for some time. Then one night Stanbridge had been to the public house and came in very late. Talk had died out, and it felt as if most people were asleep. He came over to my bed & put his hand down under the blankets. I shrank away, but he reached for me, and felt me fiercely. He was a wiry, humourless, red-headed boy. Then he got into the bed too, though he was fully clothed, & still had his shoes on: their hard leather soles scraped my feet. He was very heavy & strict, though he had some sense of the danger, & kept on saying ‘Sh’ to me, though I had not dared to say a word. He made me bite on a handkerchief while he buggered me. I cannot remember much about it except that I cried and cried, in a soundless, wretched way, & the hot pain of it, & an agonised guilt, as if it had all been my fault, about blood on the sheets-though no one ever said anything about it. Later it became obvious to me that other men in the dormitory had known about it. I was deeply aware that it was not a thing that could be appealed against. Also after that the teasing stopped, & I was shown a companionable respect. And we all learnt, when the Second Master himself came to the dormitory late at night a few weeks later, that Stanbridge’s brother had been killed in France: Stanbridge himself became clouded about & supported by the decent & entirely artificial respect that we young gentlemen accorded to the bereaved. Every week brought news of the deaths on the battlefields, often of Wykehamists who were fresh in the memories of dons & boys, & many of whom had been lavishly adored.

Things did not pick up with Strong until the next term, when he had me as his valet. I put up a slight resistance to this idea, because there was something unnatural in being sweated. In the holidays I had servants of my own, so it seemed absurd to become a paid lackey in the term. Yet Strong was very businesslike & pleasant in his proposal. Although he was a College man he had, I now knew, the reputation of not being very bright. I should say what he looked like: solidly built, with a wide, square face, cleft chin, square nose, dark, deep-set eyes, a heavy beard for a schoolboy, & thick, curly hair that was almost black. His father was a banker, not a country person, but he had lived mostly with his mother near Fordingbridge. He had rather bandy legs, & walked on the outside edges of his feet. I did not particularly need the money I got from being his valet but all the men who were valets agreed that the money was why they did it.

It soon became clear that he was very fond of me. He would make me clean his shoes & make his bed & cook his toast in Chambers over the coal fire. I did not really begin to fall in love with him until he became more obliging, calling me to him for no reason other than to have me there, or question me about something I was supposed to know-all this of course very shy & inept although it had to me the fascination of authority. But then other boys noticed that he had a softness for me, and brocked us both, so that I, who had been as unconscious as ever of anything erotic, suddenly learnt what was going on &, by some profound power of suggestion, what my feelings actually were. As soon as they said we were always together, I glowed that our secret had been revealed-although until that moment I had not known the secret myself. At first there were fighting denials, but the pleasure of affection overrode them, a pleasure oddly shared by the other boys, who were both catty and collusive. All was well in Chambers, but we were awkward when alone. I was soon idolatrously in love, & I believe he was too. One afternoon in Cloister Time when the whole College was out on war work at a farm beyond St Catherine’s Hill, digging potatoes, he took me off for a walk through the fields. We walked along arm-in-arm though he was much bigger than me. I had an intense sense of privilege & occasion, though I don’t think I envisaged anything particular happening. Nor did it. He said it wd be awfully sad when he left, but he wanted to join the War, & play his part. Then he said how perfectly furious he had been when he had heard what Stanbridge had done to me. He would have done something about it, only Stanbridge’s brother being killed had made it impossible. I said I didn’t mind, really; but he said he would never have done a thing like that. When we got back to the potato field, there were remarks. Somebody said, ‘You look a bit stiff, Strong’ & somebody else said, ‘You two look fairly tweaked.’ There was a general impression that we had made love to each other, which was pruriently celebrated by the other boys, as if on the morning after a wedding. I blushed & was delighted at this. I remember sifting through the barely damped forked earth with my hands, picking out the potatoes, the dirt packing behind my nails, & not in the least minding that we hadn’t.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.