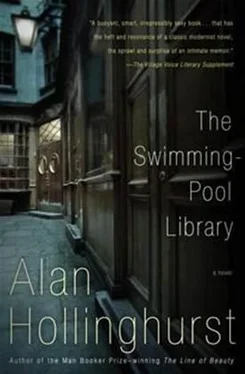

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

The man who had been at the adjacent place said ‘Oh my Christ’ and hurried out. All along the rank of urinals there was a hasty doing-up of flies, and faces that spoke both of concern and of a sense that they had been caught, turned in my direction.

I instantly pictured James, as he had described himself, kneeling over corpses on long train journeys, as a doctor honour-bound to attempt to resuscitate them, long after hope was gone. I also fleetingly saw the Arab boy, wandering off under the budding trees, and thought that if I’d never succumbed to this fantasy, I wouldn’t be in this fix now. Still, I thought I knew what to do, partly from involuntary recall of life-saving classes by the swimming-pool at school, and I immediately knelt beside the old man, and punched him hard in the chest. The three other men stood by, undergoing an ashamed transition from loiterers to well-wishers in a few seconds.

‘He didn’t hang about, he knew the old bill’d do for him, soon as look at him,’ said one of them, in reference, apparently, to their companion who had fled.

‘Shouldn’t you loosen his collar?’ said another man, apologetic and well spoken.

I tugged at the knot of the tie, and with some difficulty undid the stiff top button.

‘He mustn’t swallow his tongue,’ explained the same man, as I repeated my chest punchings. I turned to the head, and carefully lowered it, though it was heavy and slipped within its thin, silvery hair. ‘Check the mouth for obstructions,’ I heard the man say-and, as it were, echoing from the tiled walls, the voice of the instructor at school. I remembered how in these exercises we were only allowed to exhale alongside the supposed casualty’s head, rather than apply our lips to his, and the alternate relief and disappointment this occasioned, according to who one’s partner was.

‘I’ll go for an ambulance,’ said the man who had not yet spoken, but waited a while more before doing so.

‘Yeah, he’ll get an ambulance,’ the first man commented after he had left. He was well up on the other people’s behaviour.

The patient had no false teeth and his tongue seemed to be in the right place. Stooping down, so that his inert shoulder pressed against my knee, I gripped his nose with two fingers and, inhaling deeply, sealed my lips over his. I saw with a turn of the head his chest swell, and as he expired the air his colour undoubtedly changed. I realised I had not checked in the first place that his heart had stopped beating, and had ignorantly acted on a hunch that had turned out to be correct. I breathed into his mouth again-a strange sensation, intimate and yet symbolic, tasting his lips in an impersonal and disinterested way. Then I massaged his chest, with deep, almost offensive pressure, one hand on top of the other; and already he had come back to life.

It had all been so rapid and inevitable that it was only when he was breathing regularly and we had laid him down on a coat and done up his fly that I felt shaken by a surge of delayed elation. I raced up the steps into mild sunshine and hung around waiting for the ambulance, unable to stop grinning, my hands trembling. Even so, it was too soon to understand. I told myself that I had scooped someone back from the threshold of death, but that seemed incommensurate with the simple routine I had followed, the vital little drill retained from childhood along with all the more complex knowledge that would never prove so useful-convection, sonata form, the names of birds in Latin and French.

The Corinthian Club in Great Russell Street is the masterpiece of the architect Frank Orme, whom I once met at my grandfather’s. I remember he carried on in a pompous and incongruous way, having recently, and as if by mistake, been awarded a knighthood. Even as a child I saw him as a fraud and a hotchpotch, and I was delighted, when I joined the Club and learned that he had designed it, to discover just the same qualities in his architecture. Like Orme himself, the edifice is both mean and self-important; a paradox emphasised by the modest resources of the Club in the 1930s and its conflicting aspiration to civic grandeur. As you walk along the pavement you look down through the railings into an area where steam issues from the ventilators and half-open toplights of changing-rooms and kitchens; you hear the slam of large institutional cooking trays, the hiss of showers, the inane confidence of radio disc-jockeys. The ground floor has a severe manner, the Portland stone punctuated by green-painted metal-framed windows; but at the centre it gathers to a curvaceous, broken-pedimented doorway surmounted by two finely developed figures-one pensively Negroid, the other inspiredly Caucasian-who hold between them a banner with the device ‘Men Of All Nations’. Before answering this call, step across the street and look up at the floors above. You see more clearly that it is a steel-framed building, tarted up with niches and pilasters like some bald fact inexpertly disguised. At the far corner there is a tremendous upheaving of cartouches and volutes crowned by a cupola like that of some immense Midland Bank. Finances and inspiration seem to have been exhausted by this, however, and alongside, above the main cornice of the building, rises a two-storey mansard attic, containing the cheap accommodation the Club provides in the cheapest possible form of building. On the little projecting dormers of the lower attic floor the occupants of the upper put out their bottles of milk to keep cool, or spread swimming things to dry, despite the danger of pigeons.

Inside, the Club is mildly derelict in mood, crowded at certain times, and then oddly deserted, like a school. In the entrance hall in the evening people are always going to and from meetings, or signing each other up for volleyball teams or fitness classes. In the hall the worlds of the hotel above, and the club below, meet. I would always take the downward stair, its handrail tingling with static electricity, and turn along the underground corridor to the gym, the weights room and the dowdy magnificence of the pool.

It was a place I loved, a gloomy and functional underworld full of life, purpose and sexuality. Boys, from the age of seventeen, could go there to work on their bodies in the stagnant, aphrodisiac air of the weights room. As you got older, it grew dearer, but quite a few men of advanced years, members since youth and displaying the drooping relics of toned-up pectorals, still paid the price and tottered in to cast an appreciative eye at the showering youngsters. ‘With brother clubs in all the major cities of the world,’ their names and dates incised in marble beneath the founder’s bust in the hall, the large core of men who worked out daily were always supplemented by visitors needing a dip or a game of squash or to find a friend. More than once I had ended up in a bedroom of the hotel above with a man I had smiled at in the showers.

The Corry proved the benefit of smiling in general. A sweet, dull man smiled at me there on my first day, talked to me, showed me what was what. I was still an undergraduate then, and a trifle nervous, anticipating, with confused dread and longing, scenes of grim machismo and institutionalised vice. Bill Hawkins, a pillar of the place, I subsequently discovered, fortyish, with the broad belt and sexless underbelly of the heavy weight-lifter, had simply extended camaraderie to a newcomer.

‘Hallo, Will,’ he said to me now as I entered the changing-room and he came back, grunting and staring from a monster workout.

‘Hi, Bill,’ I replied. ‘How’re you doing?’ It was our inevitable exchange, in which some vestige of a joke seemed to reside, our having the same name yet, by the difference of a letter, each being called something altogether different.

‘Haven’t seen you for a bit,’ he said.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.