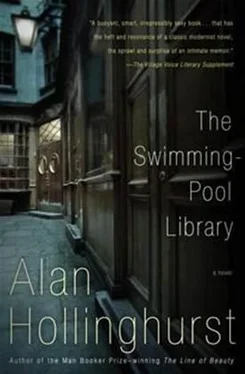

Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Alan Hollinghurst - The Swimming-Pool Library» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:The Swimming-Pool Library

- Автор:

- Жанр:

- Год:неизвестен

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:5 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 100

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

The Swimming-Pool Library: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «The Swimming-Pool Library»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The Swimming-Pool Library — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «The Swimming-Pool Library», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

I’d had a growing suspicion throughout this sordid but charming little episode, which rose to a near certainty as he opened the door and was caught in a slightly brighter light, that the boy was Phil from the Corry. He had smelt of sweat rather than talcum powder and there was a light stubble on his jaw, so I concluded that if it were Phil he was on his way to rather than from the Club, as I knew he was fastidiously clean, and that he always shaved in the evening before having his shower. I was tempted to follow him at once, to make sure, but I realised it would be easy enough to tell from seeing him later; and besides, a very well-hung kid, who’d already been showing an interest in our activities, moved in to occupy the boy’s former seat, and brought me off epically during the next film, an unthinkably tawdry picture which all took place in a kitchen.

On the train home I carried on reading Valmouth. It was an old grey and white Penguin Classic that James had lent me, the pages stiff and foxed, with a faint smell of lost time. Wet-bottomed wine glasses had left mauve rings over the sketch of the author by Augustus John and the price, 3/6, which appeared in a red square on the cover. Nonetheless, I was enjoined to take especial care of the book, which also contained Prancing Nigger and Concerning the Eccentricities of Cardinal Pirelli. James had a mania for Firbank, and it was only out of his love for me that he had let me take away this apparently undistinguished old paperback, which bore on its flyleaf the absurd signature ‘O. de V. Green’. James held the average Firbank-lover in contempt, and professed a very serious attitude towards his favourite writer. I had long deferred reading him in the childishly stubborn way that one resists all keen and repeated recommendations, and had imagined him until now to be a supremely frivolous and silly author. I was surprised to find how difficult, witty and relentless he was. The characters were flighty and extravagant in the extreme, but the novel itself was evidently as tough as nails.

I knew I would not begin to grasp it fully until a second or third reading, but what was clear so far was that the inhabitants of the balmy resort of Valmouth found the climate so kind that they lived to an immense age. Lady Parvula de Panzoust (a name I knew already from James’s reapplication of it to a member of the Corry) was hoping to establish some rapport with the virile young David Tooke, a farm boy, and was seeking the help of Mrs Yajñavalkya, a black masseuse, to set up a meeting. ‘He’s awfully choice,’ Mrs Yaj assured the centenarian grande dame. Much of the talk was a kind of highly inflected nonsense, but it gave the unnerving impression that on deeper acquaintance it would all turn out to be packed with fleeting and covert meaning. Mrs Yaj herself spoke in a wonderful black pidgin, prinked out with more exotic turns of phrase. ‘O Allah la Ilaha!’ she reassured the anxious Lady Parvula. ‘Shall I tell you vot de Yajñavalkya device is? Vot it has been dis thousand and thousand ob year? It is bjopti. Bjopti! And vot does bjopti mean? It means discretion. S-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-s-sh!’ It was such a long ‘Sh!’ that I found myself quietly vocalising it to see what its effect would be.

‘Quiet, Damian,’ the woman opposite me said to her little boy. ‘Gentleman’s trying to read.’

It was about nine when I reached home. The tall uncurtained window at the turn of the stairs still let in just enough of the phosphorescent late dusk to make it unnecessary to turn on a light. I enjoyed a proprietorial secrecy as I walked slowly and silently up, as well as the frisson of bleakness that comes from being in a deserted place as darkness gathers. There was something nostalgic in such spring nights, recalling the dreamy abstraction of punting in the dark, and the sweet tiredness afterwards, returning to rooms with all their windows open, still warm under the eaves.

The door of the flat was slightly ajar, which was unusual. I was inclined to keep it shut as I was (or had been) often the only inhabitant of the house, the businessman in the main floors below being frequently abroad. And I had occasionally witnessed Arthur pushing it to, or checking as he passed through the hall that it was closed. My heart sank as I nudged it open and heard Arthur’s voice, not addressing me-he could not possibly have known I was there-but talking quietly to somebody else. The door of the sitting-room, which was open, hid whatever was going on; the light from that room fell across the further side of the hall.

My first assumption was that he was on the telephone, which would have been reasonable enough except that he had said he hated the phone. For a sickening moment I felt that I was being somehow betrayed, and that when I went out he rang people up and carried on some other existence. A plan was afoot of which I was the dupe; he had not killed anybody at all… Then I heard another voice, just odd syllables, high-it sounded like a young girl. I heard Arthur say ‘Yeah, well I expect he’ll be back here soon.’ I made a noise and went into the room.

‘Will, thank God,’ Arthur said, half rising from the sofa, but encumbered by the heavy breadth of my photograph album, which lay open across his lap and across that of a small boy sitting beside him and leaning over it as if it were a table. It was my nephew Rupert.

Rupert had had longer than me to work out what to say. Even so, he was clearly unsure of the effect he would have. First of all he wanted it to be a lovely surprise: he stared up at me, mouth slightly open, in a spell of silence, while Arthur, too, looked very uncertain. Again I found myself suddenly responsible for people.

‘This is an unexpected pleasure, Roops,’ I said. ‘Have you been showing Arthur the pictures?’ I thought something might be seriously wrong.

‘Yes,’ he said, a little shamefaced. ‘I’ve decided to run away.’

‘That’s jolly exciting,’ I said, going over to the sofa, and lifting up the photograph album. ‘Have you told Mummy where you’ve gone?’ I held the heavy, embossed leather book in my arms, and looked down at him. Arthur caught my eye, frowned and expelled a little puff of air. ‘Blimy, Will,’ he said confidentially.

Rupert was then six years old. From his father he had inherited an intense, practical intelligence, and from his mother, my sister, vanity, self-possession, and the pink and gold Beckwith colouring that Ronald Staines had so admired in me. I had always liked Gavin, a busy, abstracted man, whose mind, even at a dinner party, was still absorbed in the details of Romano-British archaeology, which was his passion and career, and who would have had nothing to do with the way his son now appeared, in knickerbockers and an embroidered jerkin, with a Millais-esque lather of curls, as if about to go bowling a hoop in Kensington Gardens. Philippa had a picturesque and romantic attitude to her children (there was also a little girl, Polly, aged three), and Gavin allowed her a free hand, concentrating his affection for them in sudden bursts of generosity, unannounced treats and impulsive outings which disrupted the life of the picture-book nursery at Ladbroke Grove, and were rightly popular.

‘I left a note,’ Rupert explained, standing up and beginning to walk around the room. ‘I told Mummy not to worry. I’m sure she’ll see that it’s all for the best.’

‘I don’t know, old chap,’ I demurred. ‘I mean, Mummy’s jolly sensible, but it is quite late, and I wouldn’t be surprised if she were getting a bit worried about you. Did you tell her where you were going?’

‘No, of course not. It was a secret. I didn’t even tell Polly. It had to be very very carefully planned.’ He picked up a Harrods carrier-bag. ‘I’ve brought some food,’ he said, tipping out on to the sofa a couple of apples, a pack of six Penguin biscuits and a roughly sawn-off chuck of cold, cooked pork. ‘And I’ve got a map.’ From inside his jerkin he tugged out an A-Z , on the shiny cover of which he had written ‘Rupert Croft-Parker’ with a blue biro in heavy round writing.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «The Swimming-Pool Library» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «The Swimming-Pool Library» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.