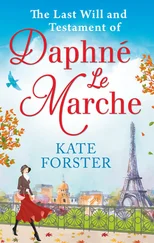

‘Yes,’ he said, looking up at her, the green eyes piercing. Maggie was disappointed, thinking of a new line of inquiry, when he spoke again. ‘And no.’

‘No?’

‘Well, it did when I first heard from you,’ he nodded towards Uri. ‘But the more I thought about it, the more it kind of made sense. I mean, he knew a lot about Israel, my father. He was an expert in the languages of this region, including, by the way, the script those ancient tablets are written in. And of course he knew Hebrew. He knew a lot about the way this country worked.’

‘Know your enemy.’ It was Uri, speaking just before Maggie had a chance to stamp on his foot. She was nodding more energetically now, hoping that she could keep Mustapha’s eyeline from straying over to Uri.

‘So he was a real expert,’ she said. ‘Go on.’

‘Well, it makes sense that he couldn’t only have got that from books. I realize that he probably spent more time here than he ever said. And that maybe he had someone to show him around.’

‘OK. Did he ever mention-’

‘Like I know he went to the tunnels, under the Haram al-Sharif. Not many Palestinians have done that. But I know he did it, though he never said so publicly. He disagreed with them passionately. “They’re a Zionist attempt to undermine the Muslim Quarter,” he said.’

‘But he went anyway.’

‘He was curious.’

‘He was an archaeologist,’ Maggie said with a sympathetic smile.

‘Always. So he wanted to see.’

Maggie imagined these two old men, from opposite ideological poles, one an ultra-Zionist, the other a Palestinian nationalist, tagging along with a tourist party through the ancient tunnels she had seen that morning. Was it possible? Could Shimon Guttman have acted as a guide to Ahmed Nour, showing him the hidden reaches of the Western Wall? Had Nour perhaps done the same for Guttman, ushering him through the buried places of the Palestinian past? No wonder Guttman had wanted to speak to Nour about the tablet. They might well have been the only two people in this divided land able to read what it said-and to understand its true meaning.

She let the silence hang a little longer. ‘Mustapha, I know it’s hard. But we really need you to think. Was there anywhere else, any other place, your father might have known of? That perhaps he had in common with Shimon Guttman?’

‘I really can’t think of anywhere.’

Maggie caught Uri’s eye, full of resignation. This is not working . He began to get up.

‘All right,’ Maggie said. ‘Let’s try this. Can we tell you the exact message Shimon Guttman left behind? See what it means to you?’

Mustapha nodded.

Maggie repeated it word for word, from memory. ‘“Go west, young man, and make your way to the model city, close to the Mishkan. You’ll find what I left for you there, in the path of ancient warrens.”’

Mustapha asked Maggie to repeat it, slowly. He shut his eyes as he listened to her. Finally, he spoke. ‘I think he has to mean the Haram al-Sharif, the exact place you went. Warrens are like tunnels, yes? And the model city. This is how we all speak of Jerusalem, Jews and Muslims.’

‘Sure, but where?’ Uri was showing his frustration.

‘When he says “Go west”, could that tell you the way to go through the tunnels?’

‘There is only one way through and I’ve done it.’ It was Maggie, her own exasperation no longer contained.

‘I am sorry.’

‘No,’ said Maggie, remembering herself. ‘It’s not your fault. We just thought there was something you might know.’

They began to walk back into the hotel. Maggie and Uri kept their heads down until they were in the car park, for fear of being recognized. Once outside, under the covered driveway by the hotel entrance, Maggie realized that she had barely offered her condolences to Mustapha. Out of politeness, she asked after his late father, how many children he had left, how many grandchildren.

‘And he was still working?’

‘Yes,’ he said, explaining about the dig at Beitin. ‘But that was not his life’s dream. His real dream, he will never see.’ His eyes were glittering.

‘And what was that, Mustapha?’ Maggie was aware that her head was cocked to one side, an amateurish bit of body language to convey ‘caring’.

‘He wanted to build a Palestine Museum, a beautiful building full of art and sculpture, and all the archaeological remains he could collect. The history of Palestine in one place.’

Uri looked up, suddenly alert.

‘Like the Israel Museum.’

‘Yes. In fact, I remember him speaking about that place. He said that one day we should have something like this. In our part of Jerusalem. Something that would show the world what used to be here, so they could see it for themselves.’

Uri’s eyes widened. ‘He said that?’

‘Yes.’ Mustapha was smiling. ‘A long time ago. “One day, Mustapha,” he said, “we shall build what they have, to show the world the history of our Jerusalem. Not abstract, but there to see and to touch.”’

‘My father must have shown it to him,’ Uri said quietly.

‘Uri?’

He gave her a brief glance. ‘I’ll explain on the way. Mustapha, can you come with us?’

Within a minute, the three of them were in a taxi, heading west across the city. The smile barely left Uri’s face, even when he was shaking his head, saying ‘of course’ to himself, again and again. When Maggie asked where the hell they were going, he looked at both Mustapha and her, his face breaking into a broad grin. ‘Thanks to our two fathers, I think our journey is about to end.’

JERUSALEM , FRIDAY , 1.11PM

Uri kept his spirits high for most of the journey. Sitting in the front, alongside the driver, and against a pounding techno beat from the radio, he took delight in explaining his father’s clue.

‘You see, I read it too quickly. I assumed that ‘Go west, young man’ had to refer to the Western Wall. It was obvious. But why would my father go to all that trouble just to do something obvious? He meant go west across Jerusalem, to the west of the city. To the place that “my brother”-your father, Mustapha-would know. The clue was in the word Mishkan . It can refer to the Temple, but also this place, the Knesset.’ Right on cue, they passed Israel’s parliament.

‘What about the rest? The path of ancient warrens?’

‘Don’t worry, Maggie. We’ll see it when we get there. I’m sure of it.’

He then turned back towards the driver, asking to borrow his mobile phone. He had done the same thing the instant they had left the Colony, then, as now, speaking intently in Hebrew for a while, before smiling and hanging up. Maggie wondered whether he had just phoned Orli: perhaps she was not as ex a girlfriend as Uri had insisted.

She was about to inquire when Uri’s face seemed to darken. He began drumming his fingers on the hard vinyl above the glove compartment, urging the driver to go faster. When Maggie asked him what was wrong, he came back with a single word: ‘Shabbat.’

They pulled into a car park, one that was worryingly empty. Uri did his best to bolt out of the car, hobbling over to the ticket office which consisted of a series of windows, all of them closed. By the time Maggie and Mustapha had caught up, Uri was already gesticulating desperately to a security guard on the door. As he feared, the Israel Museum was closed for the sabbath.

After much pleading, the guard grudgingly passed Uri a cellphone, apparently already connected. Uri’s voice changed instantly, suddenly lighter, full of warmth and humour. Maggie had no idea what he was saying, but she felt certain that Uri was speaking to a woman.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу