He surveyed the shelves almost hoping there would be nothing worth seeing, so that he could hurry away and get back on schedule.

‘Hello, Professor. How nice to see you again.’ It was the owner, Afif Aweida, emerging from behind the jeweller’s counter at the far end, a glass case housing a collection of rings and bracelets on velvet beds. He offered his hand.

‘What a remarkable memory you have, Afif. Good to see you.’

‘To what do I owe this pleasure?’

‘I was just passing through. Window shopping.’

Afif gestured for Guttman to follow him through the shop, up a couple of stairs into a back office. The Israeli looked around, noting the large, bulky computer, the old calculator, complete with paper printout, the layer of dust on the shelves. Times had been hard for Aweida, as they had for everyone in this area. The inhabitants of East Jerusalem, like the Palestinians in general, were the victims of what Shimon often thought of as a bad case of divine oversight, fating them to live in a land promised to the Jews.

Afif saw Shimon check his watch. ‘You cannot wait till my son brings us some tea? You are in a hurry?’

‘I’m sorry, Afif. Busy day.’

‘OK. Well, let me see.’ He was on his feet, surveying his stock. ‘Nothing too dramatic, but there is this.’ He held out a cardboard box with perhaps a dozen mosaic fragments inside. Shimon rapidly arranged them, like a child’s jigsaw, to discover the shape of a bird. ‘Nice,’ he said, ‘but not really my area.’

‘Actually, there is something you can help me with. A new shipment arrived this week. I am told there is more where this came from, but for now, this is what I have.’ He leaned down, resting one arm on a shabby leather chair which was disgorging some of its stuffing, to pick up a tray from the floor.

On it, arranged in four rows of five across, were the twenty clay tablets Henry Blyth-Pullen had brought to him just a few days earlier. Despite Aweida’s downbeat pitch, it was not dull-merely handling such clear remnants of the ancient past always excited Shimon Guttman-but it was hardly scintillating either. He checked his watch: 1.45 p.m. He would get through these, then be off to Psagot for that three o’clock meeting.

‘OK,’ he said to Aweida. ‘The usual terms, yes?’

‘Of course: you’ll translate all of them and keep one. Agreed?’

‘Agreed.’

Aweida brought a notepad to his lap and waited. His familiar pose, the secretary taking dictation. Guttman brought the first tablet out of the tray, felt the pleasing weight of it in his palm, not much bigger than an old tape cassette. He moved it closer to his eyes, lifting his glasses to get a sharper view of the text.

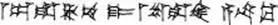

He gazed at the cuneiform markings which, even in as banal a context as this, never failed to thrill him. The very idea of a written record that stretched back more than five millennia into the past was, to him, intensely moving. The notion that the Sumerians had been writing down their thoughts, their experiences, even trivial jottings, thirty centuries before Christ and that they could be read right here, on tablets no grander or more imposing than these small bars of clay, was exhilarating. He imagined himself as one of those enormous radio telescopes, arranged in rows in the New Mexico desert, their yawning wide dishes primed to receive a signal emitted by a remote star millennia ago. Someone had written these words thousands of years ago, yet here he was, reading them right now, as if the ancient past and the immediate present were facing each other in conversation.

The first time he had been taught how to interpret the marks which gave cuneiform its name-the word literally translated as ‘wedge-shaped’-he had felt the emotional charge of it. To the naked eye, they were just squiggles that looked like little golf tees, some vertical, in pairs or threes, some on their side, also in twos and threes, arranged in various patterns, filling line after line. But ever since Professor Mankowitz had shown him how those cryptic impressions could be decoded as ‘In my first campaign, I…’ or ‘Gilgamesh opened his mouth and said…’ he had been seduced.

He dictated to Aweida. ‘Three sheep, three fattened sheep, one goat…’ he said after a glance. He could not read and understand these as quickly as he could English, but certainly as fast as he could read and translate, say, German. He knew it was a rare expertise, but that delighted him all the more. In Israel, there was no one to match his knowledge, with the exception of Ahmed Nour (not that Ahmed would ever declare himself to be living in Israel). Otherwise, now that Mankowitz had gone, it was just Guttman. Who else? That fellow in New York; Freundel at the British Museum in London; but only a handful of others. The journals always said there were only one hundred people in the world at any one time who could read cuneiform, but he suspected that was, if anything, an overestimate.

He picked up the next one. Instantly, merely from the layout of the tablet, he could see what this was. ‘A household inventory, I’m afraid, Afif.’ The next one showed the same line repeated ten times. ‘A schoolboy’s exercise,’ he told the Palestinian, who smiled and noted it.

He continued like that, setting the translated tablets onto Aweida’s desk, until there were only six left in the tray. He picked up the next one, and read to himself the opening words as if they were the first line of a joke.

‘ Ab-ra-ha-am mar te-ra-ah a-na-ku …’ He put the tablet down and smirked at Aweida, as if he might be in on the gag, then brought the tablet back to his eye again. The words had not vanished. Nor had he misread them. The cuneiform, of the Old Babylonian period, still read Abraham mar Terach anaku . I Abraham, son of Terach.

Shimon felt the blood draining from his face. A kind of queasy panic washed over him, starting in his head, then cascading through his chest and into his guts. His eye sped forward, as far as they could before the letters became cloudy and indistinct.

I Abraham, son of Terach, in front of the judges have attested thus. The land where I took my son, there to make a sacrifice of him to the Mighty Name, the Mountain of Moriah, this land has become a source of dissension between my two sons; let their names here be recorded as Isaac and Ishmael. So have I thus declared in front of the judges that the Mount shall be bequeathed as follows…

What reflex restrained Guttman at that moment, preventing him from saying out loud what he had just read to himself? He would ask himself that question many times in the days that followed. Was it an innate shrewdness that made him realize that if he spoke now he would almost certainly lose this great prize? Was it no more than the savvy of the shouk , the habit of a veteran haggler who knows that to show enthusiasm for any item immediately doubles its price, moving it potentially out of reach?

Was it a political calculation, a comprehension in a fleeting second that what he was holding in his now-trembling hand was an object that could change human history no less dramatically than if he were grasping the detonator of a nuclear bomb? Or was there a simpler explanation, one less noble than all the others: had Guttman bitten his tongue because every instinct in his body would hesitate before sharing a secret with an Arab?

‘OK,’ he said finally, hoping, by economy of speech, to hide the shakiness in his voice. ‘What’s next?’

‘But, Professor, you haven’t told me what that one said.’

‘Didn’t I? Sorry, my mind wandered. Another household inventory, I’m afraid. Woman’s.’

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу