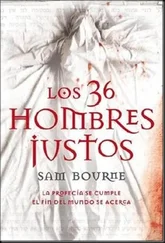

‘A little.’

‘OK. What does nas tayib mean?’

‘That’s very simple. It means a good man.’

‘Or, if we were to translate it into German, a Gutt man, nein ?

LONDON ,SIX MONTHS EARLIER

Henry Blyth-Pullen tapped the steering wheel along to the Archers theme tune. Tum-tee-tum-tee-tum-tum-tum, tum-tee-tum-tum-tumtum . He was, he decided, a man of simple tastes. He might have spent his working life surrounded by sumptuous antiques and precious artefacts, but his needs were modest. Just this-an afternoon drive through the spring sunshine, with no more onerous obligation than listening to a radio soap-was enough to cheer his spirits.

He always liked driving. Even this, a forty-five-minute run from the showroom in Bond Street to Heathrow Airport, was a pleasure. No phone calls, no one bothering him. Just time to daydream.

He did the drive often. Not to the main terminals, teeming with passengers and all kinds of hoi polloi on their way to their tacky vacations in heaven knows where. His destination was the turning almost everyone else ignored. The cargo area.

He pulled into the car park, finding a space easily. He didn’t get out straightaway, but stayed to listen to the end of the episode: Jenny breaking down in tears for a change. He got out, straightened his jacket-a contemporary tweed, he liked to call it-shot an admiring glance at his vintage Jaguar, polished to a shine, and headed for the reception.

‘Hello again, sir,’ said the guard the instant Henry walked into the Ascentis building. ‘We can’t keep you away, can we?’

‘Oh come on, Tony. Third time this month, that’s all.’

‘Business must be good.’

‘In truth,’ he said, mimicking a courtly bow, ‘I cannot complain.’

At the window, he filled in the air waybill. On the line marked ‘goods’ he wrote simply ‘handicrafts’. For ‘country of origin’, he wrote ‘Jordan’ which was not only true but suitably unremarkable. Imports from Jordan were entirely legal. Asked for his 125 number he wrote down the string of digits Jaafar had given him over the phone. He signed his name as an approved handling agent and slipped the form back under the glass.

‘All right, Mr Blyth-Pullen, I’ll be back in a tick,’ said Tony.

Henry took his usual seat in the waiting area and began leafing through a copy of yesterday’s Evening Standard . If he looked relaxed, it was because he felt relaxed. For one thing, he was dealing with the staff of BA, not Her Majesty’s Revenue & Customs department. Sure, Customs would look at the forms but he couldn’t think of the last time they had asked to open anything up, let alone a crate that had been vouched for by a recognized, and highly respectable, agent like him. The truth was, they were not really bothered with the art trade. Trafficking, whether in drugs or people, that was their game. The lead had come from the top. The politicians, pushed by the tabloids, wanted to keep out crack, smack and Albanians-not the odd mosaic fragment. As Henry had explained to his overanxious wife more than once, the uniformed men at Heathrow were playing at The Sweeney , not Antiques bloody Roadshow .

Sure enough, Tony soon emerged with a set of papers and his usual smile: Customs must have nodded the forms through. Henry Blyth-Pullen wrote out a cheque for the thirty pounds release fee and went back to his car, waiting, with Radio 4 now deep into an afternoon play, to be called into the secure area. Eventually he was beckoned forward, driving through the huge, high gates until he reached Door 8, as instructed by Tony. Another short wait and soon he was putting a single brown box into the boot of the Jag. One more signature, to confirm receipt, and the shipment was officially signed, sealed, delivered-and one hundred per cent legitimate.

When it came time to open the crate in the back room of his Bond Street showroom, he felt the same pulse of pleasure he experienced whenever a truly special consignment arrived. It was almost sexual, a stirring in the loins, that he had first known as a teenager, smoking an illicit joint at his boarding school. He levered open the top, taking care to avoid the splinters these tea-chests could skewer into your fingers. But his mind itched with that most delicious of questions, known to any child tearing away at ribbons and paper on Christmas morning: what’s inside?

Al-Naasri had told him over the phone to expect tourist souvenirs. Henry had been intrigued, assuming this was code for items brought to Jordan from somewhere else. But as he peeled off the first layers of styrofoam and bubble wrap, he felt uneasy. He saw a set of six music boxes, each in the form of a Swiss chalet in luridly cheap colours. He lifted the lid of the first one and, to his great disappointment, it played a tune. Edelweiss .

Below them were horrible, shoddy glass frames an inch thick containing patterns of coloured powder, complete with a transparently fake sticker, announcing each one as ‘Genuin Sand from Jordan River’. Al-Naasri had never let him down before but this, Henry Blyth-Pullen had to admit, had him foxed. Finally, encased in triple layers of bubble wrap and tissue paper, were a dozen nasty charm bracelets, the kind, Henry decided instantly, oiks might buy from a coin-operated machine on Blackpool pier. Of all the shipments he had received in his eighteen years in the business, this was easily the most disappointing. Handicrafts, my eye. This was tourist tat, plain and simple.

When they had spoken, Henry had thought ‘souvenirs’ was simply a euphemism, necessary when talking on the telephone. But that bloody Arab wasn’t kidding. Still, he had worked with Jaafar al-Naasri for a long time now. He had never been let down before. Falling into a chair, he now reached for the phone. He would get this sorted. He dialled and waited for the long drone of an international ring.

‘Jaafar! Thanks for this latest arrival. It’s-how shall I put it- surprising .’

‘Do you like the song?’

‘On the music boxes? Yes, er, yes. Most…tuneful.’

‘Ah, that is because of the workmanship, Henry. Look inside the cylinder drum; you can see a technique there that is very old. Ancient even.’

‘I understand.’ Listening to Jaafar, with the phone cradled in his ear, Henry moved back to the crate, where he picked out the first music box. He wrenched the wooden roof off its hinges to get a closer look at the mechanism. He would need a screwdriver.

‘And these are a local product?’ Henry asked, stalling.

Too impatient to find his tool box, Henry grabbed a kitchen knife and levered out the innards of the first music box. It was stubborn-too bloody meticulous, the Swiss, that was their trouble-but eventually it pushed out. And there, inside, sure enough, was a perfect example of a cylinder seal.

‘Oh, I now see what you mean about these music boxes, Jaafar. The mechanisms are exquisite! They could only have come from the very birthplace of the, er, music box. The place where it all began!’

‘And what about the sand displays?’

‘Well, their immediate appeal is a little less obvious.’

‘You know of course, that every grain of sand was once a much larger stone. One that has been changed, its appearance altered by time. Look hard in any grain of sand and you can see the rocks and stones of the past.’

Henry picked up the first display and smashed it against the side of his oak desk, sending sand all over the carpet. He peered out through the doorway, hoping no one out front-staff or, worse, a customer-had heard the sound of breaking glass.

There, filling the palm of his hand, was a clay tablet. Etched on it was line after line of cuneiform writing. It was covered in sticky sand now, like party glitter, but it brushed off easily.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу