After fifteen minutes of sorting the rope into two knot-free stacks, it is ready to go over the edge. I check the knot, clipped into the single carabiner secured on the purple webbing of the anchor, and, one at a time, toss each pile of rope over the cliff. Ordinarily, I would remove the knot and let the rope dangle from the anchor. This would allow me to pull the rope down once I reached the bottom; today, however, I intend to abandon it. I won’t need it after this, and right now I’m truly unconcerned about littering.

Standard practice would have me back up the anchor carabiner with a second one, the gates opposite and opposed, but I’m not worried that this one will accidentally open or fail. There is nothing the ’biner can catch on, and its rating is strong enough that I could hang two pickup trucks off of it. The webbing is new within a month, and I’m satisfied with its strength as well; it hasn’t been chewed on or chafed or significantly degraded by the sun. If I didn’t trust the webbing, I could clip my rope on a ’biner directly into one of the bolt eyelets, but I decide the setup is plenty sufficient to hold my weight on the descent.

Next, I take my Air Traffic Controller (ATC) rappel/belay device and bend each rope strand through one of the twin slots in the mouth of the device. Once they’re through, I clip my main carabiner through the rope loops. After I tighten down the lock on the carabiner gate, I’m finally on rappel. I unclip my daisy chain from the anchor webbing and back up until my weight comes onto the rope and anchor system. Checking my harness, I see that I haven’t doubled back the waist belt through the D-ring that holds it in place. Theoretically, the belt could pull through the ring, and then my weight would be suspended entirely by my leg loops. If I had two hands and weren’t in the process of bleeding to death, I would double back the belt, but right now, with water waiting below, it’s a risk I’m willing to take.

Looking down at my feet, I back up in jerking motions, feeding six inches of the ropes through my ATC with each stuttering step. At the edge, I can peek down between my legs at the dizzying six-story drop and see that the ledge I’m departing hangs out over the rest of the cliff. I’m slightly nervous about doing this rappel with just my left hand. If my grasp slips or for some reason I let go, I have no backup; I’ll accelerate down the rope, only slightly slower than in free fall, and take a hard landing next to the pool, probably breaking my legs or worse. It’s very important that I take the overhanging section slowly.

Just ease back. Little more. Little more. That’s it, Aron. Step down onto that block. No, left foot first. Good. Steady. Now your right foot. Excellent. Lean back on the rope. Trust it. Push your butt out. Straighten your legs. Now feed a little more rope out. Slowly. Sloooowly. Good. Now hold on tight.

The pucker factor is high on the upper part of the rappel. With the rope’s weight putting additional friction on my rappel device, I have to fight and pull the strands to feed them through the device bit by bit-a significant effort that saps my remaining strength-but not so much that I slide down the rope and lose my balance. It’s like trying to drive a car in 5-mph stop-and-go traffic while pressing the accelerator to the floor and controlling the vehicle’s speed by releasing the hand brake. I have to let off the brake to get going, but it’s dangerously easy to release it too far and lose control. Doing it one-handed means I don’t have any way to reach out and stabilize myself when I start to swing one direction or the other as I move my feet over the awkwardly uneven lip of the shelf. I’m most worried that I’ll let too much rope through, fall off the lip, and hit the edge of the shelf with my shoulder or my head, then let go of the rope. The poached air sucks my pores dry, and I’m tortured for three minutes as I make a prolonged series of infinitesimal adjustments and maneuvers to get my body under the shelf. Finally, I let a little more rope through the ATC, my feet cut loose off the lower edge of the shelf, and I’m dangling free from the wall on my rope, some sixty feet off the ground. A moment of giddy delight replaces my anxiety as I spin around to face the amphitheater, floating comfortably in midair. Gliding down the rope, moving faster as I get closer to the ground, I notice the echo of my ropes singing as they slide through the ATC.

Touching down, I pull the twenty-foot-long tails of my ropes through my rappel device and immediately lunge for the mud-ringed puddle. I move out of the sun and into the cool shade, brusquely swing my pack off my left side and then more delicately over my right arm, and once again retrieve my Nalgene. When I open the lid this time, I toss its contents into the sand off to my left and fill it in the puddle, scooping up leaves and dead insects along with the aromatic water. I’m so parched I can taste the elevated humidity around the pool, and it piques my thirst. I swish the liquid to rinse out the bottle and then dump that to the side as well.

Scooping the bottle through the pool twice, I again fill it with the brown water. In the time it takes me to bring the Nalgene’s rim to my lips, I debate whether to sip it slowly or guzzle away and decide to sip then guzzle. The first droplets meet my tongue, and somewhere in the heavens, a choir strikes up. The water is cool, and best of all, it’s brandy-sweet, like a fine after-dinner port. I drink the entire liter in four chugging swallows, drowning myself in pleasure, and then reach to fill the bottle again. (So much for sipping.) The second liter follows in the same manner, and I refill the bottle once more. I wonder if the water would taste as wonderfully sweet to a normally hydrated person. If the water really is this delicious, what makes it that way? Are the dead leaves stewing the liquid into some kind of desert tea?

I sit at the edge of the puddle, and, for the moment, I am enjoying myself, as though my thirst is all that really matters, and now that it’s taken care of, I am totally at ease. Everything disappears. I even cease noticing the pain of my arm. I daydream as if I’m on a picnic, sitting in the shade after a long lunch, with nothing left to do except watch the clouds roll by.

But I know the relief will be short-lived. As relaxed as I am, I have eight miles of sandy hiking in front of me to reach my truck, and I need to steel myself for it. I notice several sets of hoofprints in the sand off to my right. Someone, or a group of someones, has ridden up into and out of this box canyon since the last storm. My heart leaps to think I might come across a party of cowboys somewhere along my hike, but I know better than to yell out or hold those hopes too closely. The dried-out road apples dotting the wash for fifty yards downcanyon tell me it’s been over a day since those horses came through here. And tourists on horseback aren’t likely to spend the night.

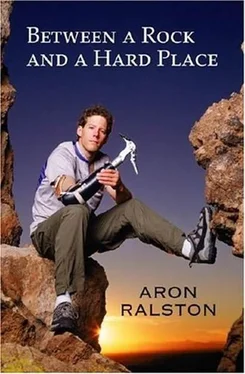

I quaff the third liter more conservatively, even nestling the hard plastic bottle in the sand for a minute or two to rummage through my pack and sort out what I can leave behind. I set aside my broken Discman and the two scratched CDs, and decide that everything else will come with me. With my digital still camera, I take a picture of my doubled rope hanging down the Big Drop and then hold the camera out in my left hand for a self-portrait with the pool in the background. It’s 12:16 P.M. I am elated to have come this far, but the photo records a grungy eight-day beard, specks of gore from the operation, and a haunted grimace. After putting the camera and the video camcorder in the outer mesh pouch of my backpack, I work at fitting the bite valve back on the tubing stub at the bottom of my CamelBak reservoir and then fill up the container with two liters of the syrupy water.

Читать дальше