Withdrawing my bloody fingers to the edge of my incision point, I isolate a strand of muscle between the knife and my thumb, and using the blade like a paring knife, I slice through a pinky-finger-sized filament. I repeat the action a dozen times, slipping the knife through string after string of muscle without hesitation or sound.

Sort, pinch, rotate, slice.

Sort, pinch, rotate, slice.

Patterns; process.

Whatever blood-slimy mass I fit between the cutting edge and my left thumb falls victim to the rocking motion of the multi-tool, back and forth. I’m like a pipe cutter scoring through the outer circumference of a piece of soft tubing. As each muscle bundle yields to the metal, I probe for any of the pencil-thick arteries. When I find one, I tug it a little and remove it from the strand about to be severed. Finally, about a third of the way through the assorted soft tissues of my forearm, I cut a vein. I haven’t put on my tourniquet yet, but I’m like a five-year-old unleashed on his Christmas presents-now that I’ve started, there’s no putting the brakes on. The desire to keep cutting, to get myself free, is so powerful that I rationalize I haven’t lost that much blood yet, only a few drops, because my crushed hand has been acting like an isolation valve on my circulation.

Another ten, fifteen, or maybe twenty minutes slip past me. I am engrossed in making the surgical work go as fast as possible. Stymied by the half-inch-wide yellowish tendon in the middle of my forearm, I stop the operation to don my improvised tourniquet. By this time, I’ve cut a second artery, and several ounces of blood, maybe a third of a cup, have dripped onto the canyon wall below my arm. Perhaps because I’ve removed most of the connecting tissues in the medial half of my forearm, and allowed the vessels to open up, the blood loss has accelerated in the last few minutes. The surgery is slowing down now that I’ve come to the stubbornly durable tendon, and I don’t want to lose blood unnecessarily while I’m still trapped. I’ll need every bit of it for the hike to my truck and the drive to Hanksville or Green River.

I still haven’t decided which will be the fastest way to medical attention. The closest phone is at Hanksville, an hour’s drive to the west, if I’m fast on the left-handed reach-across shifting. But I can’t remember if there’s a medical clinic there; all that comes to my mind is a gas station and a hamburger place. Green River is two hours of driving to the north, but there is a medical clinic. I’m hoping to find someone at the trailhead who will drive for me, but I think back to when I left there on Saturday-there were only two other vehicles in the three-acre lot. That was a weekend, this is midweek. I have to accept the risk that when I get to the trailhead, there won’t be anyone there. I have to pace myself for a six-to-seven-hour effort before I get to definitive medical care.

Setting the knife down on the chockstone, I pick up the neoprene tubing of my CamelBak, which has been sitting off to the top left of the chockstone, unused, for the past two days. I cinch the black insulation tube in a double loop around my forearm, three inches below my elbow. Tying the black stretchy fabric into a doubled overhand knot with one end in my teeth, I tug the other end with my free left hand. Next, I quickly attach a carabiner into the tourniquet and twist it six times, as I did when I first experimented with the tourniquet an eon ago, on Tuesday, or was it Monday?

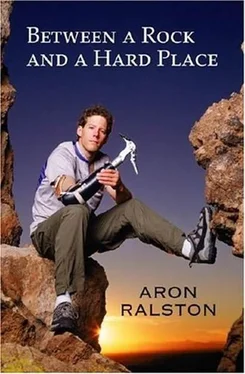

“Why didn’t I figure out how to break my bones then?” I wonder. “Why did I have to suffer all this extra time?” God, I must be the dumbest guy to ever have his hand trapped by a boulder. It took me six days to figure out how I could cut off my arm. Self-disgust catches in my throat until I can clear my head.

Aron, that’s all just distraction. It doesn’t matter. Get back to work.

I clip the tightly wound carabiner to a second loop of webbing around my biceps to keep the neoprene from untwisting, and reach for my bloody knife again.

Continuing with the surgery, I clear out the last muscles surrounding the tendon and cut a third artery. I still haven’t uttered even an “Ow!” I don’t think to verbalize the pain; it’s a part of this experience, no more important to the procedure than the color of my tourniquet.

I now have relatively open access to the tendon. Sawing aggressively with the blade, as before, I can’t put a dent in the amazingly strong fiber. I pull at it with my fingers and realize it has the durability of a flat-wound cable; it’s like a double-thick strip of fiber-reinforced box-packaging tape, creased over itself in quarter-inch folds. I can’t cut it, so I decide to reconfigure my multi-tool for the pliers. Unfolding the blood-slippery implement, I shove the backside of the blade against my stomach to push the knife back into its storage slot and then expose the pliers. Using them to bite into the edge of the tendon, I squeeze and twist, tearing away a fragment. Yes, this will work just fine. I tackle the most brutish task.

Grip, squeeze, twist, tear.

Grip, squeeze, twist, tear.

Patterns; process.

“This is gonna make one hell of a story to tell my friends,” I think. “They’ll never believe how I had to cut off my arm. Hell, I can barely believe it, and I’m watching myself do it.”

Little by little, I rip through the tendon until I totally sever the twine-like filament, then switch the tool back to the knife, using my teeth to extract the blade. It’s 11:16 A.M.; I’ve been cutting for over forty minutes. With my fingers, I take an inventory of what I have left: two small clusters of muscle, another artery, and a quarter circumference of skin nearest the wall. There is also a pale white nerve strand, as thick as a swollen piece of angel-hair pasta. Getting through that is going to be unavoidably painful. I purposefully don’t get anywhere close to the main nerve with my fingers; I think it’s best not to know fully what I’m in for. The smaller elastic nerve branches are so sensitive that even nudging them sends Taser shocks up to my shoulder, momentarily stunning me. All these have to be severed. I put the knife’s edge under the nerve and pluck it, like lifting a guitar string two inches off its frets, until it snaps, releasing a flood of pain. It recalibrates my personal scale of what it feels like to be hurt-it’s as though I thrust my entire arm into a cauldron of magma.

Minutes later, I recover enough to continue. The last step is stretching the skin of my outer wrist tight and sawing the blade into the wall, as if I’m slicing a piece of gristle on a cutting board. As I approach that precise moment of liberation, the adrenaline surges through me, as though it is not blood coursing in my arteries but the raw potential of my future. I am drawing power from every memory of my life, and all the possibilities for the future that those memories represent.

It is 11:32 A.M., Thursday, May 1, 2003. For the second time in my life, I am being born. This time I am being delivered from the canyon’s pink womb, where I have been incubating. This time I am a grown adult, and I understand the significance and power of this birth as none of us can when it happens the first time. The value of my family, my friends, and my passions well up a heaving rush of energy that is like the burst I get approaching a hard-earned summit, multiplied by ten thousand. Pulling tight the remaining connective tissues of my arm, I rock the knife against the wall, and the final thin strand of flesh tears loose; tensile force rips the skin apart more than the blade cuts it.

A crystalline moment shatters, and the world is a different place. Where there was confinement, now there is release. Recoiling from my sudden liberation, my left arm flings downcanyon, opening my shoulders to the south, and I fall back against the northern wall of the canyon, my mind surfing on euphoria. As I stare at the wall where not twelve hours ago I etched “RIP OCT 75 ARON APR 03,” a voice shouts in my head:

Читать дальше