There were two primary questions surrounding them: who could write the most accurately, and who could write fastest. The Gurney system of brachygraphy, or shorthand, brought him under its magical, mysterious spell. Brachygraphy, or an easy and compendious System of Shorthand rested on and under his pillow. It permitted an ordinary human, after some close training and prayer, to condense the usual long-winded language of their fellow beings into mere scratches and dots on a page. The reporter would copy down an orator's speech in this cobweb of markings, then rush out the door. If outside the city, in Edinburgh or some country village, he would bend over his paper while being driven in a carriage, scribbling furiously under a small wax lamp as he transformed onto blank slips of paper the strange symbols into full words-occasionally sticking his head out the window to prevent sickness along the rocky passage.

The green reporter Dickens mastered the Gurney, just as his father had once done in brief employment as a shorthand writer, but that was not enough. Young Dickens altered and adjusted Gurney-he created his own shorthand-better and quicker than anyone else's. Soon, the most important English speeches were always certified at the bottom of the page by C. Dickens, Shorthand Writer, 5, Bell Yard, Doctors’ Commons.

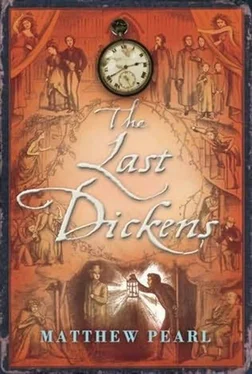

That was how he could write so much, even half a book, in the small cracks of a full schedule while in America. That was the only way his pen could keep pace with his mind and reveal the fate of Edwin Drood.

The Gurney system had years ago been replaced by that of Taylor and then by Pitman's. Rebecca had been trained in Pitman's at the Bryant and Stratton Commercial School for women on Washington Street before applying to be a bookkeeper. Fields and Osgood, after depositing the pages from the satchel representing the last chapter of The Mystery of Edwin Drood in their fireproof safe at 124 Tremont Street, did consult some of the first-rate shorthand writers in Boston (several of whom, themselves the brainier Bookaneers, had been the ones attempting to copy down Dickens's improvisations at the Tremont Temple before Tom Branagan and Daniel Sand stopped them). They would only show them a page or two, for purposes of secrecy, and did not tell them the provenance of the document. No luck-it was useless. The system, even for those very familiar with Gurney, was too eccentric to decipher more than a few scattered words.

They sent confidential cables to Chapman & Hall seeking advice on the matter. Meanwhile, quietly, Fields and Osgood made preparations with their printer and illustrator for a special edition of The Mystery of Edwin Drood , complete with the exclusive final chapter.

The first week after the retrieval of the manuscript there were endless consultations and interviews with the chief of police, customs agents, the state attorney, and the British consulate. Montague Midges, denying all accusations, was immediately dismissed from his post and interrogated by the police about his conversations with Wakefield and Herman. The Samaria was boarded by customs and an eager tax collector named Simon Pennock, using the information gathered by Osgood and the late Jack Rogers, and every member of the crew was taken into custody. The Royal Navy had been alerted, and over a matter of months the majority of Marcus Wakefield's operation was dismantled.

One morning, Osgood was called into Fields's office where he was shocked to be staring straight into the mouth of a long rifle.

“Halloa, old boy!”

The double-barreled rifle was hanging loosely behind the shoulder of a burly, ruddy man in a tight-fitting sporting outfit with high leather gaiters, knee breeches, and a cartridge belt around his wide waist. Frederic Chapman.

“Mr. Chapman, forgive me if I wear a look of astonishment,” Os-good began. “We sent our cables to you in London not two days ago.”

Chapman gave his mighty laugh. “You see, Osgood, I was in New York on some dull business for the firm, and on my way in full force to a shooting party in the Adirondacks when the hotel messenger stopped me at the train station with a cable from my office in London passing along your intelligence. Naturally I boarded the next train into Boston. I always liked Boston-the streets are crooked and the New Englandism is down to a science. I say, these”-he delicately picked up the small sheaf of pages with care and awe-“are simply remarkable! Imagine!”

“Can you make sense of it, then?” Fields asked.

“Me? Not a single speck, not a single word, Mr. Fields!” Chapman declared without any diminished excitement. “Osgood, where did you go? There you are. Say, how is it you came upon this?”

Osgood exchanged a questioning look with Fields.

“Mr. Osgood is our most diligent man!” Fields exclaimed proudly.

“Well, I should think this proves it,” said Chapman, resting his hands on his cartridge belt. “I could use men like you, Osgood. My clerks, they're worthless and hopeless creatures. Now we must set in motion a plan to read these at once.”

Fields told him how the shorthand writers they'd consulted could not make it out, and they did not want to give them too much of it to see.

“No, we mustn't let anyone else get wind of this. Clerk!” Chapman leaned out the door and waited for anyone to appear. Though it was one of the financial men who presented himself, Chapman snapped his fingers and said, “Some champagne in here, won't you?” Chapman then closed the door on the confused man and insisted on shaking both men's hands again with his hunter's iron grip. “Gentlemen, I have it! This shall be historical! Long after we are all-pardon the morbidity-out of print permanently, our names will be honored for this. The end of the last Dickens, for all the world to see! That is a triumph.

“I happen to know several court reporters who worked alongside Dickens in the capacity of shorthand writers thirty years ago; in some cases, they competed with the younger rival, attempting to replicate his altered version of the shorthand technique. Some of them, though their heads have grown white with the creeping of age, still live retired lives in London and are known to me personally. I have no doubt that for the right price their success in ‘translating’ this text will be assured.”

“Upon my word, we shall contribute liberally to such a fund,” Fields said.

“Good. I'll book my passage back early to deal with this without delay,” Chapman said. “Say, you have made a copy of the chapter, haven't you?”

Fields shook his head. “The truth is, this shorthand is of such a strange design, I fear any copies could be worthless. Dashes and lines and curly symbols not replicated exactly would render a word or paragraph potentially indecipherable. It would be like an illiterate copying out a page from a Chinese scroll. Perhaps with two or three of the best copyists checking each other. The best copyists in Boston are also the greediest, and it would be a risk to entrust them.”

“You did not even make a copy for yourself?” Chapman asked, surprised.

“Mr. Fields cannot, with his hand,” Osgood said. “We didn't know you were coming, Mr. Chapman. I would have tried, but I am afraid even the attempt to could take weeks.”

“And tracing it is out of the question,” Chapman noted, “for these papers have not exactly been well kept, wherever it is you found them, and the chemicals of tracing paper could tamper with the ink. No matter, the original shall be safe”-here he stopped to caress the end of his rifle-“even from your so-called Bookaneers. Let them try me!”

Chapman put the chapter in his case. As soon as the transcription was complete, Chapman would send a private messenger in whom he had complete trust to deliver the fully transcribed pages back to Boston, so the Fields, Osgood & Co. edition could appear well before any pirated editions.

Читать дальше