The demonstration on the steps was being performed by a man called the Fire King. He offered, for the reward of small bills, to prove his power of resisting every species of heat. “Supernatural powers!” he promised the crowd.

To the cheers and applause of his spellbound followers, Fire King swallowed as many spoonfuls of boiling oil as were matched by donations, and he immersed his hands in a pot of “molten lava.” Next, the King entered the open doors to the public house and-for a steeper fee, gladly supplied by the philanthropically minded crowd-he inserted himself into the public house's oven along with a piece of meat and came out only when the meat (a raw steak he'd held up for the crowd) was finished.

The two pilgrims to this region did not remain outside long enough to see the cooking, however, for Datchery had walked up to the black door and knocked. A man stretched out on a crusty, ragged couch granted them admission into a corridor, after which they ascended a narrow stairs where every board groaned at their steps; perhaps out of disrepair, perhaps to warn the inhabitants. The building smelled of mold and what? It was an odor that was heavy, drowsy. They made a wrong turn into a room where there sat a piano and a small audience before it; everyone turned to look at them and would not move a muscle until they were gone. Barmaids and ballet girls sat next to or on top of sailors and clerks. One man in the audience seemed to be balancing a dagger in his teeth.

Osgood could only imagine what demonstration would happen after they left, as he never heard any piano music while in the building.

They continued upward through the smoke and mist. “Here,” Datchery said with eerie finality. “Take care, Mr. Osgood, every door in life can lead into an undiscovered kingdom or an inescapable trap.”

The door opened into darkness and smoke.

“No weapons!” This was the greeting, in a gravely voice that seemed to belong to a woman.

Datchery put his club down in the hall outside the door.

Only after some slight, slow commotion was a candle lit. The small room showed itself crammed with people, most coiled together on a collapsed bed. Several were asleep and several more looked as though they could fall asleep at any moment. At the foot of the bed sat a gaunt, careworn woman with silver hair holding a long, thin piece of bamboo.

“Remember, pay up, dearies, won't ye?” she greeted the newcomers. “Yahee from across the court is in quod for a month for begging. He don't mix well as me, anyhow!”

Over a small flame she was mixing together a black treacly substance. Sprawled on the bed was a Chinese man in a deep trance, and a Lascar sailor with an open shirt mumbling to himself-both with glossy, vacant eyes. Across the Lascar's mouth, drool escaped from between rotten teeth and ran down the craterlike sores on his lips. Rags and bedclothes hung from a string to dry in the smoke. The smoke! As the woman held out the bamboo pipe, Osgood recognized the reeking smell as opium.

Osgood thought about the narratives of Coleridge and De Quincey, both of whom, like almost everyone else including Osgood, had taken opiates from the pharmacist to quell rheumatism and other physical ailments. But the writers had indulged heavily enough to experience a swirl of ecstasy and fatigue that were opium's powerful effects on the brain. As De Quincey wrote in a series of published confessions, before it became the motto of thousands, “Happiness might now be bought for a penny, and carried in the waistcoat pocket.” Osgood thought, too, about the accusation of the police against Daniel Sand that he had left so far away in Boston, that Daniel had given up everything for the thrill and ease of opiate entertainment.

“Sally's is better than Yahee's brand-you'll pay accordingly, won't ye, dearie?” the manager of the establishment repeated. “Have a whiff. After payment, of course.”

As she recited her slogans, a petite young woman on the other side of Sally's grisly bed slid to the floor with a moan.

“Is she unwell?” asked Osgood. Sally explained that the young woman was in a peaceful dream state and would be better than if she were in the terrible, unclean grog-house where the girl's mother used to take her.

Then Osgood realized. He could suddenly name the feeling he had experienced upon entering the building. It was a word he would have never guessed. Familiarity.

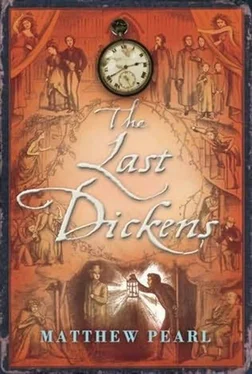

Witnessing this squalor was like seeing photographs of scenes from The Mystery of Edwin Drood! It recalled the very first scene of the book, where the devious John Jasper takes refuge in his opium dreams as he prepares to begin his villainous plans against his nephew Drood; and Princess Puffer, the old woman stirring the opium, questions her visitor. It was just as they performed the novel's scenes at the Surrey, too, but here given the actual stench of the drug and its hopelessness.

Here's another ready for ye, deary. Ye'll remember like a good soul, won't ye, that the market price is dreffle high just now?

Osgood's hope had been proven right! Datchery, consciously or not, must have absorbed something about the writing of the novel if he knew of this place. Then, a less settling feeling touched his nerves as he looked back at Datchery, standing behind him. Datchery and Sally were eyeing each other with the familiarity of a suitor and his former love.

A sudden and unexpected movement pulled away Osgood's attention: four white mice had scurried across a dirty shelf and over the occupants of the bed. Sally assured them they were very tame pets and, after a few clumsy attempts, managed to light another candle as if to demonstrate the highly civilized nature of a two-candle colony. The light revealed a ladder running up into a hole in the ceiling. In the time they had been standing there, a Malaysian sailor had left the room and a Chinese beggar had entered, left, and entered again. Sally spoke to the beggar-apparently her usual plea for advance purchase of her opium but now in Chinese. She also berated a ship's cook from

Bengal, whom she called Booboo, who was apparently not only a drug purchaser, but her lodger and servant.

THERE WAS REPETITION in the operation. After being given a shilling from a customer, the dealer would toast a thick black lump, which she had been mixing slowly with a pin, over the flame of a bro-ken lamp. When it was hot enough, the black mixture was inserted into the cup of the bamboo pipe, which was just an old glass ink bottle with a hole pierced in its side. The customer would then suck the end of the whistling pipe until the opium had been used up-usually after only a minute at the longest.

As Sally prepared the concoction, she gave a hard stare at Os-good-impatient with the lack of payment. Even one of the half-sleeping opium eaters now seemed to take a curious interest in the well-dressed publisher. Osgood, meanwhile, under the wet rags at his feet, noticed a small booklet or pamphlet among other soiled papers. Though the lighting was too dark to make out the details, the booklet's battered cover looked like he had seen it before.

“Well, dearies,” Sally the opium manager said, scowling a little, “is there something more ye want here, if it isn't any whiffs?” The Lascar meanwhile had now managed to stand and was also gazing at them.

Osgood felt a second wave of nausea from the newly thickened fumes. As he kneeled down to take a breath in the clearer air near the floor, he also slipped the booklet into his pocket. Datchery asked if he was all right.

“Some air,” Osgood responded, woozy from bending over. He found the door and climbed down one flight of stairs to an open window at the landing. Leaning his head out, he closed his eyes, still burning from the smoke. He realized when he opened them again that his vision was blurry from painful tears, and he tried to dry his eyes with a handkerchief. The air felt soothing on his face-though it was hot, it seemed like an ocean breeze compared with that cauldron upstairs.

Читать дальше