‘Least he’ll never make us,’ laughs Ellis.

‘Off you go then,’ grins Rudkin.

‘Me?’ says Ellis.

‘Give him the keys,’ Rudkin tells me.

I pass them forward, the Vice guy still staring in at me.

‘You fucking fancy me or something?’

He smiles, ‘You’re Bob Fraser aren’t you?’

I’ve got my hand on the handle, ‘Yeah, why?’

Rudkin is saying, ‘Leave it, Bob.’

The prick from Vice is backing away from the car, doing the usual, ‘What’s his problem?’ speech.

Rudkin is out talking to him, glancing back.

Ellis turns round, sighs, ‘Fuck,’ and gets out.

I sit there in the back of the Rover, watching them.

The Vice copper walks off with Ellis.

Rudkin gets back in.

‘What’s his name?’ I ask.

Rudkin’s looking at me in the rearview mirror.

‘Just tell me his name?’

‘Ask Craven,’ he says. Then, ‘Fuck, get in the front. He’s off.’

And I’m into the front, the car starting, and we’re off.

I pick up the radio, calling Ellis.

Nothing.

‘The cunt’s still yapping,’ spits Rudkin.

‘Should’ve let me go solo,’ I say.

‘Bollocks,’ he says, glancing at me. ‘You’ve done enough bloody solo.’

We’re at the junction with Harehills.

Fairclough’s white Cortina with its black roof is turning left into Leeds.

I try Ellis again.

He picks up.

‘Get your fucking finger out,’ I’m shouting. ‘He’s heading into Leeds.’

I cut him off before he can piss off Rudkin any further.

Fairclough turns right on to Roundhay Road.

I’m writing:

4/6/77 16.18 Harehills Lane, right on to Roundhay Road .

Foot down, writing:

Bayswater Crescent .

Bayswater Terrace .

Bayswater Row .

Bayswater Grove .

Bayswater Mount .

Bayswater Place .

Bayswater Avenue .

Bayswater Road .

Then he’s right on to Barrack Road and we keep straight on.

‘Right on to Barrack Road,’ Rudkin’s shouting at me, me into the radio at Ellis.

I’ve got Ellis in the rearview, indicating right.

‘He’s on him,’ I say.

Ellis’s voice booms through the car: ‘He’s pulling up outside the clinic’

We go right and pull up past the junction on Chapeltown Road.

‘Just some fat Paki bitch with a ton of shopping,’ says Ellis. ‘Coming your way.’

We watch the Cortina pass us and turn back up the Roundhay Road.

‘Proceeding,’ I say into the radio and Rudkin pulls out.

‘Tell Ellis to pick him up again at the next lights,’ says Rudkin.

I do it.

And Rudkin pulls in.

We’re at the entrance to Spencer Place, to Janice.

I look at him.

‘You got some sorting out to do,’ he says and leans across me, opening my door.

‘What you going to say?’

‘Nowt. Be here at seven.’

‘What about Fairclough?’

‘We’ll manage.’

‘Thanks, Skip,’ I say and get out.

He pulls the door to and I watch him drive off up the Roundhay Road, radio in hand.

I check my watch.

Four-thirty.

Two and a half hours.

I knock on the door and wait.

Nothing.

I turn the handle.

It opens.

I step inside.

The window open, drawers out, bed stripped, radio on:

Hot Chocolate: So You Win Again…

The cupboards bare.

I pick a letter off the dresser.

To Bob .

I read it.

She’s gone.

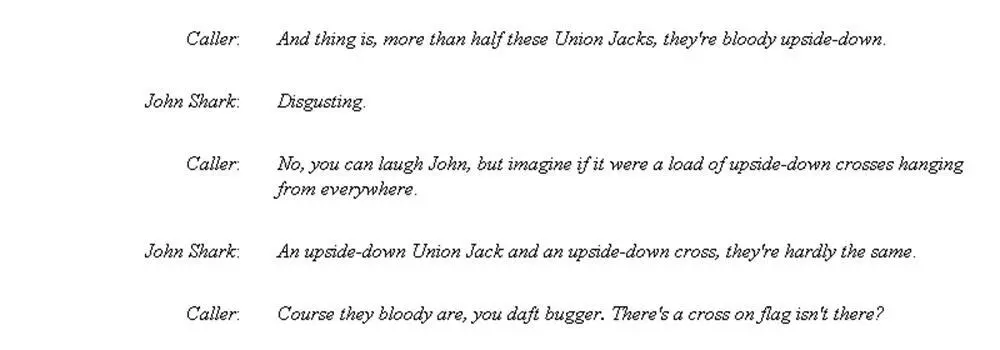

The John Shark Show

Radio Leeds

Sunday 5th June 1977

‘There’s been another,’ Hadden had said.

But I’d just lain there, waiting, watching tiny black and white Scottish men on their knees, tearing chunks of turf out of the ground with their bare hands, the phone slipping in my own hand, thinking, Carol, Carol, is this the way it will always be, forever and ever, oh Carol?

‘Press conference is tomorrow.’

‘Sunday?’

‘Monday’s a Bank Holiday.’

‘It’s going to play hell with your Jubilee coverage.’

‘She’s not dead.’

‘Really?’

‘She got lucky.’

‘You think so?’

‘Oldman reckons he was disturbed.’

‘Hats off to George.’

‘Oldman says you should get in touch the minute you receive anything.’

‘He took something then?’

‘Oldman’s not saying. And neither should you.’

Oh Carol, no wonders for the dead?

Jubelum…

There was another voice in the Bradford flat, there in the dark behind the heavy curtains.

Ka Su Peng looked up, lips moving, the words late:

‘In October last year I was a prostitute.’

She had travelled ten thousand miles to be here, sat across a dim divide of stained chipped furniture, her skin grey, hair blue, ten thousand miles to fuck Yorkshire men for dirty five pound notes squeezed into damp palms.

Ten thousand miles to end up thus:

‘I don’t know many of the others so I’m usually alone. I do the early time on Lumb Lane, before the pubs close. He picked me up outside the Perseverance. The Percy they call it. It was a dark car, clean. He was friendly, quiet but friendly. Said he hadn’t slept much, was tired. I said, me too. Tired eyes, he had such tired eyes. He drove us to the playing fields off White Abbey and he asked me how much and I said a fiver and he said he’d give it to me after but I said I wanted it first because he might not pay me after like happened before. He said OK but he wanted me to get into the back of the car. So I got out and so did he and that’s when he hit me on the head with the hammer. Three times he hit me and I fell down on to the grass and he tried to hit me again but I closed my eyes and put up my hand and he hit that and then he just stopped and I could hear him breathing near my ear and then the breathing stopped and he was gone and I lay there, everything black and white, cars passing, and then I got up and walked to a phone box and called the police and they came to the phone box and took me to hospital.’

She was wearing a cream blouse and matching trousers, feet together, bare toes touching.

‘Can you remember what he looked like?’

Ka Su Peng closed her eyes, biting her bottom lip.

‘I’m sorry,’ I said.

‘It’s OK. I don’t want to remember, I want to forget, but I can’t forget, only remember. That’s all I do, remember.’

‘If you don’t want to talk about it…’

‘No. He was white, about five feet six inches…’

I felt a hand on my knee and there he was again, as if by magic, smiling through the gloom, meat between his teeth .

‘Stocky build…’

He patted his paunch, burped .

‘With dark wavy hair and one of them Jason King moustaches.’

He primped at his hair, stroking his moustache, that grin .

‘Did he have a local accent?’

‘No, Liverpool perhaps.’

He arched an eyebrow .

‘He said his name was Dave or Don, I’m not sure.’

He frowned and shook his head .

‘He was wearing a yellow shirt and blue jeans.’

‘Anything else?’

She sighed, ‘That’s all I can remember.’

He winked once and was gone again , as if by magic.

She said, ‘Is that enough?’

‘It’s too much,’ I whispered.

After the horror, tomorrow and the day after .

Suddenly she asked, ‘You think he’ll ever come back?’

Читать дальше