Mrs. Meyer-Murphy opened the purple door with feverish anticipation.

“Officer Berringer!”

When she saw the rest of us her eyes narrowed and she began to blink rapidly.

“What’s all this?”

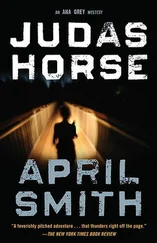

I stepped forward and offered my hand. “Ana Grey with the FBI.”

Mrs. Meyer-Murphy continued to squint as if she’d suddenly gone blind.

Andrew touched her shoulder.

“Remember, Lynn, I told you? We were bringing in the FBI?”

She’d been pumping my hand with both of hers. Autopilot. Cold, long fingers. She was tall and strikingly underweight, short black hair with short bangs that kind of triangulated out over the ears. Sassy. On a good day. She wore a mismatched yellow cardigan over a T-shirt and blue nylon track pants. She was tired and wired at the same time, sallow skin, and the circles underneath her eyes profound. She was in that state of fluid grief where tears just come and go. But now the nervous blinking stopped. She peered at me with all the spirit she could muster.

“Thank God you’re here.”

“We’re going to do everything possible to get your daughter home safely and quickly. May we enter the house, ma’am?”

“Please.”

She stepped back.

The gang, which had been pawing the driveway impatiently, trampled through the door.

It was like opening day at the big sale at Target.

In a matter of minutes they had fanned out through the house, hoisting metal briefcases and coils of wire.

Mrs. Meyer-Murphy stared. Strangers were chugging up her steps and opening her closets.

“What are they doing?”

“We’re taking over your home.”

Wide-eyed. “You are?”

“Where is your husband, Mrs. Meyer-Murphy? Who else is in the house?”

Inside the door a heap of helmets and Rollerblades sat underneath a hat rack. She led me through a living room dominated by a fireplace of river rock. Family pictures on the mantel. I would get to those. A Santa Monica uniform was leaning over a coffee table, reading off the top of a pile of newspapers that had spilled onto a rose-patterned rug. There were shoes all over the place, kid sneakers and grown-up running shoes.

“My little one’s at school,” said Lynn Meyer-Murphy. “I took her to school, was that wrong?”

“Not at all. I’ll send an agent over.”

The tears—“I didn’t know what else to do!”

“It’s okay, Mrs. Meyer-Murphy. Beautiful home.”

There were gingham-covered sofas, distressed-pine tables, quilts and old-fashioned brass lanterns — artfully arranged but incongruous. The country style of the inside seemed to have nothing to do with the Spanish style of the outside. Or maybe the purple door held a symbolism that I missed.

“This morning, around six o’clock, I actually drank a martini. Is that crazy?”

“Understandable.”

“But it had absolutely no effect.”

As we passed through an arched doorway I noticed a cluster of miniature watercolors — tiny corsets and hats and high-button shoes. Commercial quality, obviously trained.

“Those are nice.”

“They’re mine. I’m a clothing designer and my husband is the manufacturer. A good idea at the time,” she added dryly.

In the kitchen the husband was half seated on a bar stool, talking on the phone. Lynn threw up her hands at the sight of him.

“Ross. Get off.”

He held up an index finger, telling us to wait while he continued to talk, focused on the floor.

“Ana Grey with the FBI.” Badging him. “I need you to hang up the phone immediately.”

He lowered the receiver. “It’s my phone.”

I stayed cool. I did not engage his anger.

“The lines need to be clear in case your daughter calls.”

“Oh, really? I never thought of that.”

He had the body type where the fat goes to the shoulders, round and bulky on top, a waist pinched by a belt too tight for those fancy jeans, stocky powerful legs. Balding. A light beard, color indiscriminate, which he was rubbing up and down.

“This is my husband.”

“She’s Meyer,” he said dolefully. “I’m Murphy.”

I gave it a smile.

Ramon hustled in, whipping a screwdriver from his tool belt.

“The police already hooked something up,” the dad said, indicating a small tape recorder attached to the phone.

“I know, sir, but we have to install our own equipment.”

“How are we doing?”

Now Andrew entered the kitchen, trailed by another Santa Monica police officer, statuesque, with blonde hair in a French braid. She had been the first responder. Her arms were strong and capable beneath the tight-fitting midnight blue uniform but her broad Slavic cheekbones were oily, eyelids heavy with fatigue. She had been on her feet for hours. Seeing another female on the job was a relief for both of us; we exchanged brief smiles.

“I just want to say one thing.” The dad pivoted on the bar stool. His chin was up, weary eyes defiant. “You already know this, Andrew.”

I cringed. Police officers like to be addressed by their rank. So far neither one of the Meyer-Murphys had gotten it right.

“Juliana is loved. She comes from a loving home. She is a good kid. She doesn’t drink, doesn’t smoke— anything. ”

Andrew said, “I hear you.”

The police officer put a fist on her hip and shifted weight, keeping her expression neutral. She had heard it, too.

“Juliana has never even been late without calling,” the dad went on. “Something happened to her, because she would never do this to us.”

“We know something happened to her,” began the mom a little desperately.

“Do you have a recent picture of your daughter?”

They had already been to the shoe box with the sheaves of family photos like a mixed salad of time — trips to Big Bear and fifteen years of Halloween — and pulled the standard school portrait, one of those cookie-cutter images that reduced the victim to an everyday teenager with long brown hair and a pleasantly chubby face, along with a black-and-white full-body shot of her holding on to a tree, an exaggerated pose with her butt sticking out, imitating a model, with a tight self-conscious smile.

“Has Juliana ever run away?” I asked.

The dad rolled his eyes.

“I know you’re tired and you’ve been over this—”

He put up his palms in submission. “No. Okay? My daughter has never run away.”

“Does Juliana have a boyfriend?”

“Are you kidding? She has no friends at that school.”

“She’s doing fine,” countered the mom.

“What school are we talking about?”

“Laurel West. It’s a private academy.” Ross seemed to like the word. “She just started there, just when we moved into this house.”

New house, new school. New money? I was making handwritten notes.

“How is Juliana doing at Laurel West?”

“Maintaining a C average,” the dad said with some sarcasm. “In middle school she was pulling A’s.”

“How do you account for the change?”

Neither parent had an answer.

“Can you give me a general idea of her activities?”

They looked at each other. “Well,” said Lynn, “she likes to hang at the Third Street Promenade.”

“Was she at the Promenade yesterday afternoon?”

“Not yesterday. Yesterday she was going over to her friend Stephanie Kent’s house. She does have friends. He thinks he knows her. He doesn’t know her at all.”

“I don’t know my own daughter?”

Lynn ignored him, gripping the back of a bar stool.

“They had to work on a science project,” she continued deliberately. “They had to make a car out of paper.”

Ross: “For this we spend fifteen thousand dollars a year.”

Читать дальше