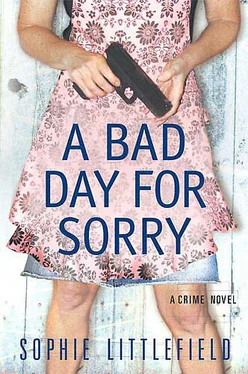

The Raven, as Stella raised it up and pointed at him, got his attention. Stella could feel just a faint tremor along her arm, down to her trigger finger. It would be a real shame to shoot Roy Dean by accident. And that’s what it would be, if she was provoked like that. An accident. But bad things happened every day.

“You listen to me real clear,” she hissed. “I know about that jacket. That’s the one Chrissy had on when she came to me the first time, ’cept she couldn’t get the sleeve over her sling. Roy Dean, you know what irony is?”

Roy Dean, eyes fixed on the gun, shook his head and swallowed hard.

“Well, it’s when the outcome of events isn’t what you’d guess from what all leads up to it. Like Chrissy, see, she told me she had been saving for that jacket since last fall. She said on double coupon day she’d take whatever she’d saved and put it in a jar, and finally she had enough to buy the jacket. Only the same day she buys it, she gets her arm broke and she can’t even wear it proper. See? Irony.”

Roy Dean fixed his gaze on the floor and refused to look at her. “Or another example might be us talking here,” Stella continued. “Getting everything all worked out, me spending my valuable time shaping you into a productive member of society and all, and then you say one stupid little thing and I have to shoot you dead. That would be ironic.”

She slowly lowered her gun arm, gave Roy Dean a final glare, and left.

She was still shaking a little as she bounced along the rutted track, pushing the Jeep harder than it cared to go, taking the turns fast enough that the wheels threatened to lift up off the road.

That jacket. That damn jacket. She’d listened to Chrissy’s tearful story with sympathetic fury, but only later did Stella figure out that it reminded her of something that had happened a week before she finally took care of Ollie once and for all.

It was an unremarkable Tuesday afternoon three years ago. She’d come home from the grocery with a bunch of daffodils. Jonquils, her mother had called them. Pat Collier used to grow them in every bare spot in her yard: under trees, along the fence, between rocks. Her mother was never happier than when the flower bulbs pushed their shoots up through the last of the snow, when the tight-rolled buds flung themselves open on a sunny early-spring day.

They had fresh-cut bunches for two bucks sitting in buckets of water outside the FreshWay, and Stella brought one home, thinking of her mother the entire time. Pat had been gone two years by then—pancreatic cancer, mercifully quick. As Stella was reaching up to the top shelf for her mother’s old white scallop-edged pitcher, Ollie came stomping into the kitchen, scratching his wide ass. He took one look at her flowers lying there on the counter and demanded, “Where the hell do you get off spending my money on shit like this?”

She’d started to tell him it was only two lousy dollars, started to say she’d been thinking about her mother that day, missing her, but before she could get any of those thoughts out, he’d taken a whack at her that sent her toppling off the step stool and left the pitcher lying in a dozen pieces on the floor.

By the time she got back to the highway, Stella had herself almost under control. She slowed as she approached the cluster of gas stations and fast-food joints before the entrance ramp, and after a split second’s consideration, eased into the drive-through lane of the Wendy’s. Not on her diet, but she hadn’t missed a workout for weeks, so that had to be a few thousand calories she’d worked off.

As the line of cars made its slow trek around the parking lot, Stella got her gun locked back up in the box. By the time she got up to the order screen, her fury had simmered back down to its usual bubbling simmer.

“Number three,” she said. “And a chocolate Frosty. Better make it a large.”

Stella visited thebottle of Johnnie Walker Black before her date, just to make sure there was enough left for a powerful belt before bed. She unscrewed the top and inhaled—held it—then replaced the cap with a mild sense of regret. She was running low—and that was an errand she couldn’t put off. Johnnie was a staple item in Stella’s pantry.

But she never drank before her standing Sunday night date with Todd Groffe. It would be bad form, since he couldn’t join her, being thirteen and all.

Todd let himself in the front door without knocking at a little after seven. “Damn them damn girls,” he said by way of greeting.

“What’d they do this time?” Stella asked, getting a couple of cans of Red Bull out of the fridge and tearing open a bag of Flamin’ Hot Cheetos.

“Got in my dresser and got my damn boxers and they’re wearin’ ’em around the house over their clothes and shit. And Mom thinks it’s cute so she won’t make them take ’em off. She’s all like taking their pictures and stuff.”

Todd’s twin sisters were six. Stella, like everyone else in the world besides Todd, thought they were adorable. Todd’s father wasn’t in the picture anymore, and his mother, Sherilee, worked long hours during the week and brought work home on the weekend. They lived in a little house a few doors down from Stella, and Sherilee had a hard time with the upkeep on the place, not to mention paying the mortgage.

But on Saturdays Sherilee got the girls a sitter and took Todd out on the town. Stella admired her for that. Sherilee took her son to Burger King, to action movies, to play paintball. They went to Wal-Mart and played laser tag and mini golf.

Sunday night it was the girls’ turn, and Todd came over to Stella’s. They shared a secret passion: they were both America’s Next Top Model junkies. Stella TiVoed the show, and she and Todd ate junk food and critiqued the outfits and the judging and tried to figure out who was really nice and who was just pretending to get along with the other girls. Meanwhile, Sherilee took the girls to Disney movies and Pizza Hut and Fantastic Sams and Sears.

Tonight, though, Stella had a hard time concentrating on Tyra and her crew as they shuttled the models through a photo shoot in what looked like a muddy jungle. Her thoughts kept going back to Roy Dean and his insolent, stupid expression as he denied that he was seeing a new girl.

She had a bad feeling about this one. He might turn out to be one of the ones who required creative thinking, a step up to an intensified program of discouragement.

Stella didn’t relish this aspect of the job—the turning of the screw, the dialing up of the pressure, the creation of new varieties and levels of pain. She understood that there were people in the world—plenty of them—who got their kicks from hurting others, who experienced a rush of pleasure to see other human beings contorted in agony. Heck, if she were to advertise for an assistant—someone to wield the whip or rubber hose or cattle prod or pliers or lit cigarette so she could keep her hands clean—she’d probably have applicants lined up out the door.

But her business didn’t work that way. Stella knew too much about pain—the kind inflicted on the innocent, the defenseless, those whose worst sins were bad judgment and displaced loyalty. And she’d pledged to stop it. Not every abuser, everywhere—there were simply too many. But if it was in her power to help a woman in Sawyer County, she did so. And gradually word reached sisters and cousins and best friends and acquaintances further afield, down through the Ozarks and up to Kansas City and over to Saint Louis and—as the months grew to years and Stella learned how to turn vicious and conscience-deficient men into cowering repenters—across state lines.

Stella picked off the sons-of-bitches one by one, leaving their women free to breathe easy, to live without dread as their constant companion. And now this sideline threatened to overtake her real job, the shop she’d inherited from Ollie, supplying the women of Prosper with sewing notions and keeping their sewing machines in good working order. Every time she thought she’d earned some time off, a new woman would show up, terrified or battered or both, but finally ready to make it stop. And Stella knew what kind of courage that took—and she never turned a client away.

Читать дальше