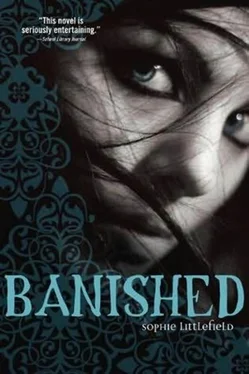

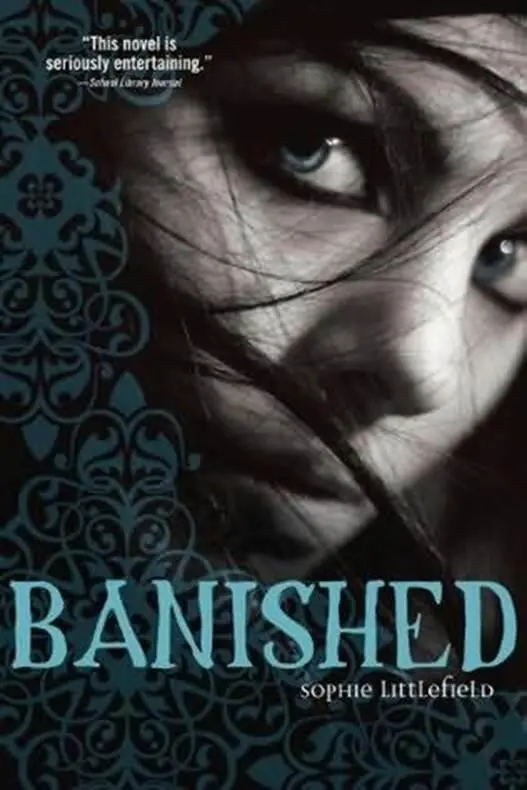

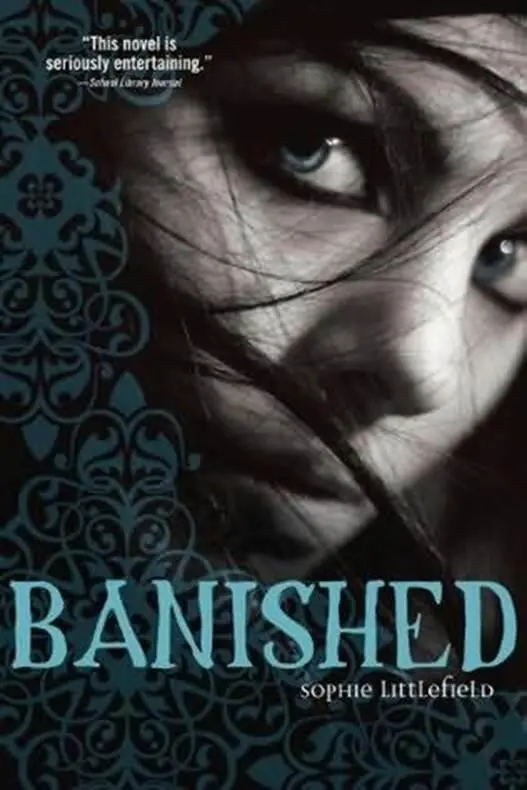

Sophie Littlefield

Banished

The first book in the Banished series, 2010

For Sal.

Growing up is hard, but you are doing a beautiful job.

This book was touched by many hands along the way, and I am grateful to you all.

Barbara Poelle, my agent who employed the roadside-assistance-phone-call and cocktail-napkin methods to develop my idea,

Claudia Gabel, who took a chance on me,

And Stephanie Elliott, my editor, who worked tirelessly to help me shape the story.

Writing this book reminded me of a time when I was doing my best to grow up, and I would like to thank the friends who were there. Bob-first and foremost. Mary. Julia, Sonja, Anne, and MaryAnn. Joellen and Margaret, and Ellen and John. And of course Kristen and Mike, who are always there.

JUNE 1995

W AKING UP HURT . Her head pounded and there was something in her eyes, something sticky and warm that made it hard to see .

She blinked hard and her eyes cleared, and she realized she was in a car .

Not just any car-her boyfriend’s car. It was a pretty white Celica, and she brushed her hand against her lap, feeling smooth, silky fabric, and remembered-it was prom night, and they were driving out to Boone Lake and he’d brought champagne, a bottle on ice in a cooler. She had slipped into the girls’ bathroom to fix her lip gloss and dab on a little extra perfume before they said goodbye to all their friends, to the school gym decorated with streamers and helium balloons, to the teachers, who smiled and nodded at them because they were nice kids, kids who got good grades and didn’t make trouble .

Except that her boyfriend had been drinking since they got to the prom, and he wasn’t drunk, no, not drunk exactly, but they’d been laughing as he took the turns on State Road 9 just a little too fast, his hand slipping along the folds of her emerald green skirt .

And she hadn’t stopped him. Because she liked having his hand there. And she couldn’t wait to kiss him some more. And she liked going fast and reckless around the turns because it felt like the future, felt like the day when they would drive away from Gypsum and never come back .

But something had happened .

There were no lights in the car now, not even the glow of the dashboard. But the headlights were still on, one shining straight into the woods, to the right of the tree they’d hit .

The other beam twisted at a crazy angle. It lit up his body, lying on the ground ten feet from the car, bent in a way that didn’t look the least bit natural .

She started screaming, yanked at the buckle of her seat belt and pushed against her door-it wouldn’t open, it was stuck or jammed, and she crawled to the driver’s seat, her knees grinding on something sharp-oh, it was the windshield, the windshield had shattered, and she realized with horror that it was her boyfriend’s body that had broken it. He never wore his seat belt-he’d gone flying through the windshield, across the hood of the ruined Celica, and landed on the hard ground, broken and bleeding .

The driver’s-side door opened easily and she stumbled out of the car, tripping on the hem of her dress, her beautiful strapless dress that no one knew had come from the St. Benedict’s thrift shop in Tipton, that fit her like it had been made for her alone .

She bunched the skirt in her fists and ran to her boyfriend, stumbling in her high heels before collapsing on her knees next to him. His hand, thrown out palm-open as though he’d been reaching for something, twitched and his lips moved. His eyes were glassy and unfocused and she bent close to hear what he was trying to say .

“ Hurts…,” he managed, licking his dry, cracked lips .

“ No, no, please don’t…,” she murmured as she tugged his tuxedo jacket open as gently as she could .

What she saw made her throat close with fear. It was too much. There was too much damage. The wound was open and black and glistening in the moonlight, so much blood draining into the cold, dry earth .

Her hands flew to the wound, her fingers working quickly to find the edges of the gash, the words coming to her lips even before she realized she’d made a decision .

But he spoke first. “I… I love… ”

His voice was so weak she almost missed it, but comprehension flickered in his beautiful brown eyes, and he looked at her the way he did when he picked her up for school, the way he had the first time she’d passed in front of his locker last year, the way he did when he searched the crowd for her face after every play at football games .

It was a look that saw her, knew her , really knew her, the way her mother never would and her father, whoever he was, never chose to. It was the look she’d hung every dream, every foolish hope on, and as he blinked twice, his eyes rolling up and going opaque, she said the words .

She said the words the way her grandmother had taught her, the syllables slipping like gossamer ribbons past her lips, words she’d chanted a hundred times on a hundred long-ago nights lit by sputtering candles and her grandmother’s eyes bright with purpose. A hundred times, a hundred nights, but tonight was the first time she prayed with all her soul that the words would work .

A twitch, a sigh-she broke off in the middle of a word whose sound was burned into her memory, but whose meaning she didn’t really know, not the way her grandmother did. Her boyfriend twitched again and blinked, and she stilled her fingers on his face .

“ Don’t leave me,” she whispered. “Oh, please don’t leave-” Her heart thudded hard in her chest because he wasn’t gone; he’d almost died but she’d brought him back, she’d said the words .

He was back .

She was bending to kiss him, to throw her arms around him, when his eyes blinked again and stayed open-

And there was nothing there .

“ Vincent,” she breathed, her heart going cold. “Vincent, please, please, Vincent, please- ”

But he said nothing. His eyes were empty and his lips were still, and the forest around them was dark and silent as a stone .

NOW

WHEN I WAS EIGHT, the social workers finally made Gram send me to school. Until then, she told the authorities she was homeschooling me, but after years of her never turning in her paperwork or showing up for the mandatory meetings, they finally got fed up and told her I had to go to regular school. Gram gave in; she knew when she was beat.

The first thing I noticed about the other kids was that they all looked like they could be on TV. I called them Cleans. Their clothes were new and ironed smooth. Their hair was shiny and combed. Their nails were trimmed and free of the black grime that I’d had under mine as long as I could remember. No one had to tell me that, compared with these other kids, I was dirty.

That didn’t stop the kids on the bus from reminding me. By the end of my first humiliating ride to school, I’d been called a bunch of names and accused of having cooties and lice and a witch for a grandmother. It was the same thing on the ride home, even though Mr. Francheski pulled the bus over, stood up and hollered, “ Was all you kids raised in barns? Where’s your manners? Be nice to this new girl. ”

Читать дальше