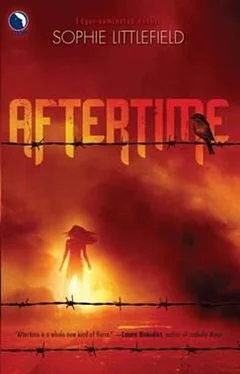

“Here,” Faye said abruptly, veering off to the left, past the fenced-off area where the bike Smoke had traded was parked next to other motorcycles and a few bicycles and skateboards. “The cheap seats.”

Cass hadn’t noticed them the night before-a row of canvas cots lined up next to the fence. In nearly all of them, motionless forms slept under drab, rough blankets, a few possessions piled under the ends of the beds.

Cass followed Faye to the end of the row, trying not to stare. At the very end a woman with long gray hair escaping its braid sat with her back to them at the edge of her cot, bent over her knees; too late Cass realized she was throwing up.

“Aw, shit, Gloria,” Faye exclaimed. “Here?”

“I’ll clean it up, I’ll clean it up,” the woman said hastily, her voice reedy and frail, a girl’s voice in a middle-aged woman’s body. “I’m sorry, I think I must have eaten something-”

“You mean, like a fifth of cheap gin,” Faye growled. “I’ll send someone. You didn’t get it on the bed, did you?”

“No, no, I didn’t. I wouldn’t do that.”

“Okay, well, I brought you someone who wants to talk to you. Take a walk with her. We’ll have this taken care of when you get back.”

“Yes. Yes, thank you,” Gloria said. She stood and started to walk down the path along the fence, not even looking at Cass, who hurried to catch up.

“You’re the girl wants to get in the Convent,” she said when Cass fell into step with her, stealing a sideways glance as though she was afraid of being found out. “They told me you’d come.”

Cass saw pale green eyes in a weathered face, lashes bleached by the sun, cheekbones that were still regal. Gloria had once been a beauty, but Cass saw something else, something that was as familiar to her as the chipped, heavy mugs at the meetings: more regrets than a human being could keep hidden, so that they found their way to the surface, traced in the faint lines and creases of her skin.

“I do want to get in,” she said carefully. “I need your help.”

The corner of Gloria’s mouth twitched, a tic that only underscored her anxiety, and darted a glance at Cass. “How do I know?”

“Know what?”

“That you’re who you say you are. That you’re not one of theirs.”

“One of…whose?”

Gloria’s tic intensified and she pressed a fist against her mouth, pushing hard enough to turn her knuckles white. “They could have sent you. Mother Cora and the rest. To spy on me.”

“Gloria…I don’t know who that is,” Cass said, trying to contain her impatience. “I just got here. I’ve never been in there. I need your help…please.”

“They’re not supposed to come in here,” Gloria whispered, walking with her shoulders hunched. “It’s Dor’s rule. It’s his rule .”

“The people…from the Convent, they aren’t allowed in here? In the Box?”

“They can’t come in here.”

“But I’m here. They let me in here. So, I can’t be from there, right?”

Cass felt a little silly trying to reason with Gloria, but she could tell that the woman’s fear was real. Very gently, Cass touched her thin shoulder. Gloria startled at the touch, but after a moment she sighed and gave Cass another sidelong glance, pushing at the long gray hair that had come loose and tumbled around her shoulders.

“I wish I had an elastic,” she said. “For my hair. Do you have an elastic?”

“No, I’m sorry,” Cass said.

“Okay. That’s how it is-anytime you think of something that would actually be useful, you can never find it.”

“You mean…”

“In my house, I lived on the first floor of a nice old house. You should have seen it…I had a collection of tea tins. The ones with the pretty designs on them. Some of them were my mother’s. Oh, some of them were very old. And I don’t know, they may have been valuable, to someone, but I didn’t even care about them. They were just…always there, you know?”

She sketched a shelf in the air with her fingers, and Cass knew she was seeing the tins in her mind, the way they looked in her kitchen. Cass had done the same thing a thousand times; nearly everyone had-remembering the things that were lost.

But then Gloria chopped the air with the hand that had been tracing a memory, a harsh gesture followed by a sharper exhalation. “I never used them. They were empty, all of them, and they sat there and I looked at them all the time and I never took them off the shelf and put anything in them. And then-one day, in the Convent, I was on washing. Me and a woman named…something. Maybe it was Alice. We were pinning the clothes on the line. We had the cheap clothespins, a pack of a thousand someone got from the Wal-Mart, but, you know, Before. And they were in this plastic bag and they kept spilling out and we tried to twist the top closed but it just kept opening, all those clothespins lying on the ground, and I thought, my tins-it would have been perfect. The clothespins in the tins, and I wished right then that I had one of them, even one, just one. I would put the clothespins in the tin and there would be that one perfect thing. The one thing that was the way it ought to be. You know?”

And the thing was, not only did Cass know but Gloria’s explanation was dead-on. She’d had the same complicated regret herself, over and over, the mourning for some small thing not because she missed the object itself but because in that moment everything seemed off. All solutions were imperfect solutions. And that wasn’t a bad thing, necessarily, because you learned to improvise, you learned to make do. Except for once in a while when it hit you like this.

“I know,” she said, and touched Gloria, gently.

Gloria looked at her, then looked at the arm where Cass had touched her, and her eyes clouded and she picked at her crusty chapped lip. “Why do you want to go in there? It’s not nice there.”

“Oh, I don’t. That’s not why I’m here. I don’t want to join. I’m looking for my daughter. Ruthie.”

As she said the name the feeling was there again, the fear that Ruthie was not in the great looming stadium, that she was nowhere near here. Maybe she was nowhere at all anymore.

Gloria put a hand to her cheek and frowned. “How old is your daughter?”

“Almost three.” Three in September, if anyone was still keeping track by then.

Gloria shook her head. “There’s little ones there. But they change all their names when they’re baptized.”

“Baptized?”

“Yes. Into the Order. In the ceremony, where they take their first communion and get their new names.” There was a note of sympathy in her voice, and she fixed her troubled gaze on Cass, her confusion momentarily lessened. “Tell me about your little girl. What does she look like?”

So Cass told: the hair so pale in the sun that it looked like flashing dimes. The rosebud mouth that could crumple into a wobbly frown one moment and lift into a blazing smile the next. The fold in her chubby arms where the baby fat was still smooth and soft.

As she talked Cass found herself speeding up, panicking, with the knowledge that her baby was months older now, that the rounded elbows and dimpled knees might have disappeared, that her hair would be longer and she would have a dozen new freckles and have learned to do things Cass couldn’t even imagine. Cass couldn’t know all the ways Ruthie would have grown and changed, and it felt like a betrayal.

“I don’t know,” Gloria said, interrupting Cass midsentence, shaking her head. “It’s too hard to know. And they change them. They mix them up like they mix me up. I heard talk.”

“What do you mean? What kind of talk?”

Gloria twisted her mouth into an expression of fury. “ Hypocritical talk,” she spat. “The kind I can’t stand. The kind that drove me right back out here.”

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу