“I’m in Bebek.”

“I’ll get a head start.” An order, then. “Don’t worry, I’ll roll you home.” Their standard joke, Leon’s apartment building just down the hill from the Park Hotel, before Aya Paşa made its wide curve.

“Give me an hour.”

“From Bebek?” Surprised, an edge now.

“Take a look outside. It’ll be a crawl in this. Just save me a stool.”

The domino players were looking down, pretending not to listen. But what would they have made of it anyway? Leon ordered a tea, a way of thanking the barman for the phone. The glass was warm in his hand, and he realized he was cold everywhere else, the wet beginning to seep through his shoes. And now the Park, everyone looking and not looking, Tommy’s old-boy voice getting louder with each drink.

“Rain check,” he said to Mihai, getting into the car. “You free tomorrow?”

Mihai nodded.

“Something’s up. We’re having a drink at the Park.”

“Very exciting, the tobacco business.”

Leon smiled. “It used to be.”

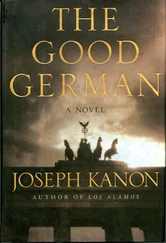

In fact, it had been sleepy, as routine and predictable as a Book of Hours. Agents bought the cured Latakia leaf, and he arranged the shipments, then took the train to Ankara to get the export permits. Leave Haydarpaşa at six, arrive the next morning at ten. That’s how it had started, carrying things on the train for Tommy, papers they couldn’t put in the diplomatic pouch, something for the war effort. No money involved then. An American helping out, not just standing around at the club getting drunk with Socony and Liggett & Myers and Western Electric, the men interchangeable, lucky businessmen sitting out the war. Tommy asked him to help Commercial Corp. buy up chromium, so the Germans wouldn’t get it, and suddenly he was in the war after all, the peculiar one that played out over dinner at Abdullah’s or those consulate receptions where the sides lined up on either end of the room, cocktail wars. What surprised him later, when he knew more, was how many others were in it too. Tracking shipping through the straits. Collecting gossip. Turning a commercial attaché who needed the money. Everyone spinning webs, watching one another, the Turkish Emniyet watching them. Nothing sleepy anymore.

“I’ll drop you home. You’ll want to change.”

“No, just back to the village. I want to go to the clinic. Look in.”

Mihai waited until they were almost there. “How is she?”

“The same,” Leon said, his voice neutral.

And then there was nothing to say. Still, he’d asked. Anna was still alive to him, a presence, not just someone in Obstbaum’s clinic who had retreated into herself, gone somewhere behind her own eyes. People used to ask all the time-painful questions at the club, an awkward concern at the office-but gradually they began to forget she was still there. Out of sight, out of mind. Except Leon’s, a wound that wouldn’t close. Any day she might come back, just as quickly as she had gone away. Someone had to be there waiting.

“You know what I think?” Mihai said.

“What?”

“Sometimes I think you do this for her. To prove something. I don’t know what.”

Leon was quiet, not answering.

“Do you still talk to her?” Mihai said finally.

“Yes.”

“Tell her we got a boat out. She’ll like that.”

“Past the British patrols?”

“So far. Otherwise we’d be in Cyprus. Tell her three hundred. We saved three hundred.”

He took the same side street back, the same garden entrance. He’d expected to have to ring, but the door was unlocked and he frowned, annoyed the staff had been so careless. But no one was trying to get out and who would want to get in? The clinic was really a kind of nursing home, a place to be out of the way. Dr. Obstbaum had been one of the German refugees welcomed by Atatürk in the thirties to help the new republic get up on its feet. The ones who could afford it had moved to Bebek or, closer in, Ortaköy, where hillsides covered in fir trees and lindens may have reminded them of home. Or maybe, lemminglike, they had simply followed the first settler. Most of the clinic’s medical staff was still German, which Leon had thought might help, her own language something she would understand, if she was still listening. But of course the nurses, the people who bathed her and fed her and chattered around her, were Turkish, so in the end he realized it didn’t matter and now he worried that she was more isolated than ever. Dr. Obstbaum himself encouraged Leon to talk.

“We have no idea what she hears. This form of melancholia-it may be a matter of responding, not awareness. Her brain hasn’t shut down. Otherwise she wouldn’t be breathing, or have any motor functions. The idea is to keep up the level of activity. Over time maybe it grows. So, music. Does she hear it? I don’t know. But the brain does, somewhere. Something functions.”

Not disturbing music, but things she knew, had played at home. Lovely notes to fill the silence in her. If she heard them.

“Most of the time I think I’m talking to myself,” Leon had said.

“Everyone here talks to himself,” Obstbaum had said, a puckish joke. “One of life’s great pleasures, evidently. You at least are being asked.”

“It’s late,” the nurse said in Turkish, a hushed whisper, her eyes glancing down to the water dripping from his coat.

“Is she asleep? I’ll just say good-night. I’m sorry about-”

But the nurse was already opening the door, brusque, the client’s whims no business of hers. He’d sit and talk, the way he always did, and she’d have to check back again, another round, but it was a private clinic and he was paying.

Anna was lying in bed, the room shadowy, only a dim night-light on. When he touched her hand, she opened her eyes, but looked at him without recognition. It was the disconcerting thing, the way she took in what was happening around her without responding. Having her hair brushed, people moving across the room-things happened far away, just little blurs of movement.

“How are you feeling?” he said. “Warm enough? There’s a terrible storm.” He nodded toward the French windows, the sound of rain on the glass.

She didn’t say anything, but he no longer expected her to. Even her hand didn’t touch back. When he talked, he answered for her, silent responses to keep things going. Sometimes, sitting next to her, he’d actually hear her voice in his head, a ghost conversation, even worse than talking to himself.

“But this is nice, isn’t it?” he said, indicating the room. “Cozy. Gemütlich. ” As if a change of language would matter.

He let her hand go and sat down in the chair.

When they first met, she’d never seemed to stop talking, bubbling over, switching from German to English as if one language couldn’t contain it, everything she had to say. And her eyes had been everywhere, ahead of the words sometimes, waiting for them to catch up, lighting her face. The odd thing was that the face was still her own, stopped in time, the wonderful skin, the soft line of her cheek, everything just the way it always had been, aging itself put off while she was away. Only the eyes were different, vacant.

“I saw Mihai tonight. He sends his love. He said they got a boat through. People are getting out again.” Something that might register, what she cared about. Don’t try to startle her, Obstbaum had said, just ordinary things, domestic matters. But how did Obstbaum know? Had he been to where she lived now? Did it matter to her that Fatma had been ill, sent her sister to do the cleaning? “Three hundred,” he said. “So they must be operating again. Mossad. Who else could it be? A boat that big.”

He stopped. The last thing he should have said, a reminder. Obstbaum thought it had happened then, when the Bratianu sank. Corpses bobbing in the water. Children. Her brain turning away from it, drawing a curtain. Obstbaum had even suggested she be put in a garden room, not a front one facing the Bosphorus, where ships passed all day, each one a possible reminder. Leon had gone along with him. Everyone in Istanbul wanted to see the water-in Ottoman times there had been laws about builders blocking the view-so a garden room was cheaper. And it was pleasant, looking toward the hillside, cypresses and umbrella pines and a Judas tree that dropped pink blossoms in the spring. A fortune back home but something he could manage here. And not a boat in sight.

Читать дальше