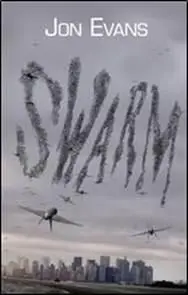

Into the belly of the beast , I thought.

The airplane looming above us in the red light of the setting sun had a bulbous body like a whale, with high and oddly twisted wings. A truck could have driven up its rear ramp and into its cavernous hold. It occurred to me that twenty-five years ago, when I was a kid who wanted to be an astronaut, I had watched the space shuttle land on the very runway that stretched into the formless desert beyond the plane.

Edwards Air Force Base around us was the size of a small town, but the empty wasteland that surrounded it made it seem fragile and impermanent, as if a divine wind might at any moment rise and sweep everything manmade into the endless annihilation of the desert. I had never been on any military base before and everything seemed strange and surreal. I felt both exhausted and wired, like I was being kept awake by amphetamines. It was hard to believe that this was actually happening, that I was really in this bustling martial hive, waiting to board the airplane that would take me to fearsome Colombia.

I looked over to Sophie. She was the real reason we were here; I was, as usual, an afterthought, her plus-one. She grinned at me excitedly. A week earlier, I would have returned that grin with interest. Instead I forced a fake smile and looked away, a dull knife twisting in my guts.

The interior of the cargo plane was an enormous tubular cave, its metal walls bristling with racks and tools, its ceiling covered by lights, ducts, wires, crawl spaces and access platforms. Its hold was full of boats. Their inverted hulls looked like thirty-foot long pistachio shells, held in place by a complex web of straps like giant seat belts.

“Coast and river interdiction,” Reyes explained, noting my perplexed look. “We give the Colombians a lot of hardware. For all the good it does.”

It was Lisa Reyes who had brought us here. She was a Drug Enforcement Administration agent, and looked the part: lean and wiry with muscle, wearing a dark suit, with high cheekbones, a sharp chin, unnaturally red hair, and a nose that had been broken at least once. She stood and moved like an athlete, perfectly balanced, coiled for action. Between her physical presence and her profession I felt uncomfortably like I was standing beside a feral animal.

When Reyes had appeared in our lab earlier that morning and introduced herself, I had briefly been terrified that she had come to arrest us. Sophie and I occasionally partook of party drugs. But it was something else that had brought her, something far more serious and mysterious: a triple homicide. The murder of DEA agent Michael Kostopolous and two Colombian government officials, in Bogota, in broad daylight, while driving at high speed. A death from above.

Michael Kostopoulos. When I had first heard Reyes pronounce his name, I had thought for a moment that I was dreaming.

“What are we waiting for?” I asked. There seemed no reason not to proceed up the ramp, but the uniformed men ahead of us had made no move. I was dressed for Pasadena, not the high desert, and as the sun set the night air was growing teeth.

Reyes shrugged resignedly and pitched her voice to carry. “Hurry up and wait. That’s the Air Force way. If any of these flyboys ever actually did anything in an expeditious manner, they’d get in trouble for making all the rest of them look bad.”

“I heard that,” said one of the men ahead of us, turning to give her a look. He was tall, with charcoal-coloured skin and the name OKOCHA emblazoned opposite AIR FORCE on his jungle-camouflaged chest. I didn’t know exactly what his shoulder badges signified, but they looked impressive.

She smiled at him sweetly. “Oh dear, was that my outside voice?”

“Reyes,” the other Air Force officer said – Harrison, stout and grey-haired – “you’re lucky there are civilians on this flight, or we’d have you field-test our new FYAUYF emergency deplaning system.”

“FYAUYF?”

“Flap your arms until you fly.”

“Probably be a softer landing than the last one you gave me.”

Okocha grunted. “Don’t get fussy. Any landing you walk away from, that’s a good landing.”

Another Air Force man appeared atop the ramp and waved us up. We ascended, and he took our boarding passes. They looked just like the ones for commercial flights. I supposed the military had to keep track of passengers too.

His eyes narrowed when he saw Sophie’s pass and mine. “James Kowalski,” he read aloud. “Sophie Warren. What outfit are you with?”

I shrugged uncertainly and looked at Reyes, who explained, “Civilians.”

“You’re taking civilians to Colombia?”

“It’s all right,” she said, “they’re with me.”

He looked at her skeptically, then to Harrison and Okocha for confirmation, before shrugging, acquiescing, and motioning us onwards.

“Don’t worry,” Reyes assured us for the third time, “you’ll be perfectly safe.”

We proceeded towards the nose of the plane, to where a row of seats folded down from the walls. I sat beneath an axe mounted beside a sign that said For Emergency Exit Cut Here, and fastened my seat belt. The orange earplugs Harrison gave me seemed to make the whole world grow more distant, intensified the feeling that I was dreaming or hallucinating. Only twelve hours ago I had expected to spend tonight watching a movie.

I started when the airplane began to move. So did Sophie, sitting beside me. The few tiny portholes were mounted too high to see anything but sky. The noise when the engines throttled up was overwhelming even through the earplugs, and the sideways acceleration as we hurtled across the desert felt odd and uncomfortable. Sophie took my hand and gripped it tightly. She didn’t like flying at the best of times. She didn’t like not being in control.

Then we lifted off, and were skyborne; en route, incredibly, to Colombia.

With her eyes closed against fear Sophie looked even younger than she was. Reyes had been visibly skeptical when Sophie was introduced to her as Dr. Warren. Twenty-five years old, with her hair ponytailed and a spray of freckles around her upturned nose, wearing old jeans and an XKCD T-shirt, she looked more like an intern than an associate professor of engineering with her own Caltech research laboratory.

We were in the belly of a military jet headed for Bogota because the DEA had requested Sophie’s expert technical knowledge and advice regarding the extraordinary means by which Michael Kostopoulous and his Colombian counterparts had been murdered. Or at least that’s what everyone other than Sophie and I thought. And if Lisa Reyes had come to us a week earlier, I would have figured the same.

Now, though, I thought differently.

I was glad that the engine noise precluded speech at anything below a scream. Just then talking to Sophie was the last thing I wanted to do. Instead I let my exhaustion rise within me and consume me like an all-enveloping cloud of smoke.

When we finally landed I was asleep on a pile of life jackets, wrapped in a blanket Okocha had found somewhere. I stumbled dazed and bleary to my feet. According to my iPhone it was 4AM, Colombia time. We lined up inside the rear gate, only to discover that it had jammed shut.

“Remember,” Reyes said drily as the crew chief fiddled with the controls, “we’re the superpower.”

After about ten minutes the gate finally descended, revealing another runway and another airbase. The only indications that we had entered a new country were that all the signs were in Spanish and everything was shabbier. Some of the buildings and vehicles hadn’t been painted in months, and the roads were marred with cracks and stubborn patches of grass. But the soldiers who greeted us looked tough and well-equipped.

Читать дальше