As always, the hardest part had been getting started, and now she was relaxing into the dive. Without fins, she had to pull herself hand over hand along rocks on the sump’s floor, which began to incline downward again. No matter how carefully she moved, she stirred up more silt. Bowman had stirred up surprisingly little. The rebreather emitted no bubbles, made only a soft sighing sound as she inhaled and exhaled. She descended gradually, clearing her ears to equalize the pressure every two or three breaths.

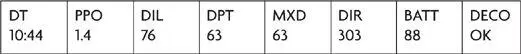

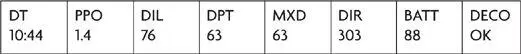

She flicked her gaze upward and the HUD was there:

Arriving at the bend in the tunnel, Hallie knew she was about halfway through. The unstable weight of the big pack on her back and the near-zero visibility made the going awkward, but at least there were no squeezes tight enough to require doffing the pack. The one thing that gave her pause was the awareness that she was doing this dive on a system without redundancy. That violated the cardinal rule of cave diving, which stated that every one of a diver’s systems should be triply redundant: lights, reels, cutting tools, computers, air, regulators, everything. And that was just for ordinary cave diving. This was even more extreme.

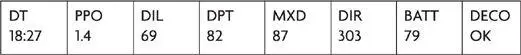

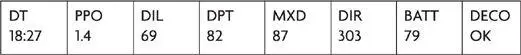

Finally, the sump began to angle upward. She glanced at her HUD:

She ascended slowly, giving her body plenty of time to off-gas accumulated nitrogen, keeping the decompression light green. Eventually she was able to stand on the gently sloping bottom. Breaking the surface, she turned 360 degrees, orienting herself. It was as she remembered. She was in the middle of a subterranean lake whose smooth surface stretched like black satin far beyond the reach of her lights. Overhead, the cave ceiling rose in a curving dome almost one hundred feet high. The rock here, with heavy iron content, contained bright red strata sandwiched between thicker striations of whitish lime, giving the appearance of a giant layer cake.

Bowman stood at the edge of the sump, waiting. She tapped a fist on top of her head, the diver’s signal for “All okay,” and slogged toward him, the water growing shallower as the bottom angled up. The sump wall here was vertical and two feet high, almost like being in a swimming pool. She took off her pack, shoved it as far as she could up to Bowman. He set it aside, bent over, and extended both hands. Hallie braced her boots on the rocky face of the sump and grasped his wrists. Bowman popped her out of the water like an angler landing a perch, grabbed her by the waist, and set her on her feet on the cave floor.

When she pulled off the full-face mask, he put his hands on her shoulders. Keeping his light on her chest, he peered straight into her eyes and held his gaze there and, crazy though it seemed, one mile deep in a supercave, on a mission that could save millions of people from horrible deaths—or not, if they failed—Hallie decided he was going to kiss her.

AND, AS CRAZY AS IT SEEMED, SHE REALIZED THAT IT WOULD not be unwelcome. Yes, there was a developing crisis on the surface. Yes, they were on a mission more important than anything she’d ever done. And yes, she and Bowman had known each other for only just over a single day. But if life had taught her anything, it was that messages from her gut could be trusted. More, actually: should never be ignored . Her aborted time at BARDA had been a painful object lesson. Even more of one had been her father’s early death. It was not that she and he had not had wonderful times together. They had, too many to count, and that was really the sharp end of this death. The future should have held decades more times like that. Except there was no “should” in time’s passage or acts of nature. The only things “should” applied to were people, to her, to decisions she could make, actions she could take. It did not require a second lesson like the loss of her father to drive that one home. And last of all, wrapping around everything else, was this: things are different in caves. As the old curandero had hinted and as she knew, caves were amplifiers, like great mountains. Mere dislike could quickly curdle into rage. And affection—well, that could turn to something else, too.

But Hallie had learned to recognize the look in a man’s eyes before he kissed her for the first time. Some looked hungry, some fearful, others worshipful, and suddenly Bowman didn’t look like any of those. Instead, he seemed serious, focused, clinical almost. Then she understood. He was checking for any signs of vertigo or pupillary dilation. Finally he smiled, let his hands drop, and took a step back.

“You look fine. How’d it go?”

She cocked her head, squinted at him. Had he been toying with her? Like winking back at BARDA? She couldn’t tell. “No problems. The HUD mask took a little getting used to, but otherwise, okay. How about you?”

He seemed surprised by the question, as though caught off guard by the fact that someone might be caring about his welfare.

“Same. I had some time on these rebreathers. It’s not your typical cave dive, though. The situational awareness is something you can’t simulate.”

“You mean the fact that we might as well be on the far side of the moon.”

“Right.”

“I think the only one we have to be concerned about is Rafael.”

At the word “we” Hallie saw him glance at her, but he did not appear to take it as any kind of challenge. “I agree.”

“He’s just older and doesn’t have as much time underground as we do.”

“Whose idea was it to bring him?”

“Mostly David Lathrop’s. There was concern at his agency about relations with Mexico. Arguello covers that, and the native population as well.”

“You have to admire his grit.”

That conversation ended, and then it was her turn to look into his eyes, and it wasn’t for vertigo or disorientation.

“How was I supposed to take that wink back at BARDA, Mr. Bowman?”

“ Doctor Bowman to you, ma’am.” He was smiling. Great teeth , Hallie thought. When she was growing up, her mother had told her, countless times, Pay attention to a man’s teeth because they’ll tell you a lot about him. You want good breeding teeth when the time comes . Her mother, the horsewoman.

He appeared to consider her question very seriously. “Well, maybe it was gratitude. I thought we were finished. But then you pulled that group together—a very impressive thing to see.”

“Maybe?” She watched his eyes and once again thought of ice in great mountains: Alaska, the Alps and Andes, ancient ice of glaciers and crevasses, night-blue ice only the passage of centuries could create, too deep and cold for any life. But now, so much closer, she saw something that had escaped her before—tiny specks of gold glinting in the blue ice. Or was it a trick of light, reflecting off some odd cave crystal? She moved her head slightly, changing the angle, but those gold flecks stayed.

“Why are you looking at me like that?” he asked.

Why indeed? “I thought there might be something in your eye.”

“My eyes feel fine.”

“And they look fine.” What had they been talking about? Oh yes . “So it was about gratitude for some team building.”

“I was very grateful. We all were.”

“Anything else, Dr. Bowman?”

A half smile, the cool blue eyes thawing. “You’re a beautiful woman, Hallie.”

You’re a beautiful woman . She had encountered that approach before, the “open and honest,” feigned-neutral-innocence posture. But there had always been something neither open nor honest lurking just below the surface, a dark craving. Bowman’s words did not strike her that way. It was her turn to toy.

Читать дальше