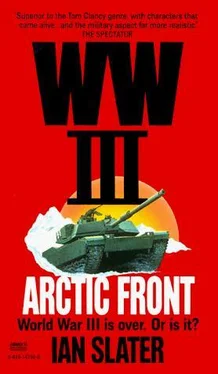

Ian Slater - Arctic Front

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian Slater - Arctic Front» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Ballantine Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Arctic Front

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ballantine Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- ISBN:0-449-14756-8

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Arctic Front: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Arctic Front»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Arctic Front — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Arctic Front», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“We’ve been painted,” warned Anderson. The missiles, at over forty-two hundred miles an hour travelling faster than a rifle bullet, were streaking toward the American formation.

The F-14s began evasive measures, but Shirer’s Tomcat was hit as it rose sharply before a dark cleft in the cliff erupting with massed machine-gun fire, the Tomcat’s wings going into the swept position for more maneuver, its turbofans screaming on afterburner. Shirer felt a shudder. The tail actuators were severed.

“Eject! Eject!” he yelled. Anderson pulled the eject handle. There was a bang, the explosive bolts disengaging.

Knowing his RIO was out, Shirer pulled his eject and the next moment was shot out in the rocket-assisted Martin-Baker ejector seat. The freezing Arctic wind howled about him as he reached the apogee of the thrust. He began to fall, heard the snap of the chute opening, and in flickering flare light spotted Anderson below, off to his left, as they descended toward the snow-covered southern end of the high, rocky island.

They had been illuminated by the flare light for only a second or two, but it was enough for the six-man troop of the elite Russian SPETS commandos, who, unseen by the Americans, came up out of their deep, rock-roofed tunnel complex and, invisible because of their white winter overlays against the snow, ran with the controlled pace of top athletes. Despite their heavy weapon load, they continued sprinting toward the island’s narrower, southern end.

Anderson, from the downed Tomcat, had barely finished wrapping up his chute when Shirer quickly released himself from the chute before it could drag him over the seventeen-hundred-foot-high edge of the cliff. The SPETS were almost upon them.

“Ne dvigat’sya!”— “Don’t move!” Neither the pilot nor his RIO knew a word of Siberian, but they understood the lead commando’s shouted command, and stood, hands raised.

The first two commandos knelt, covering them with their AK-74s. As per regulation, at least one of the elite SPETS troop, the tail-end Charlie, spoke English — and without a trace of an accent. “What airfield are you from?” he asked them both, his gaze settling on Shirer who, despite the fact that the Russian was only several feet away, couldn’t make out the commando’s face beneath the dark makeup and the hood of the white overlay.

“My name is Franklin G. Shirer. My rank is colonel in the U.S. Navy. My service number is—”

“Who’s the senior officer?” snapped the Russian commando, his infrared goggles giving him a grotesque, bug-eyed, alien appearance.

“I am,” Shirer told him.

“You!” said the commando, turning immediately to the RIO. “What airfield are you from?”

“My name is Captain Walter B.—”

“ Vozmite ego!” —”Take him!” ordered the commando. Two of the other SPETS grabbed the captain. Shirer instinctively moved to help and felt himself lifted off the ground, the pain hitting a moment later, the blow to his stomach winding him so acutely that despite the howl of the wind moaning across the icy crust of the island, he could hear himself gasping hoarsely, his windpipe making a rasping sound as he struggled for breath. Amid the flashes of the Siberian ZSU-23 quads and streams of tracer gracefully arcing and climbing skyward he glimpsed his RIO at the edge of the cliff. “What airfield?” shouted one of the Russians holding him. Anderson wouldn’t answer. The next second he was gone off the cliff, his screams quickly lost beneath the loud rattle of the Siberians’ AA quads.

“Jesus!” shouted Shirer. “You bastards—” A SPETS hit him again, and he blacked out.

The navy’s air attacks from the Salt Lake City were fierce, fearless, and ineffective. The only thing that they achieved was a pervasive sense among the Siberian tunnel garrison of the superiority of their “Saddam Bunker” defensive measures-lessons learned from the Iraqis’ experience during the massive American and Allied bombing of ‘91.

Even if the starye perduny— ”old feats”—in Russia’s Frunze Military Academy had not absorbed the experiences relayed to them by their pupils, the Republican Guard survivors, the lesson of the logistical brilliance of the Americans had been duly recorded by the Soviets’ Liberation Army Daily.

It was not so much the lesson of the U.S.’s “Smart” bombs, as, despite the propaganda spread about by what Novosibirsk called the unwitting dupes of the Western media, the Americans’ laser-guided weapons constituted only 7 percent of the total bombs dropped, the remainder being World War II iron bombs, some of these turned into GBU — guided bomb units— with the Pave penny laser seeker conversion kits. No, it was the logistical capability, the “tooth to tail” supply lines feeding and in general maintaining over a quarter-million men and machines with everything they needed, from 5.56 rifle rounds, HEAT (high explosive antitank) rounds, Starlight infrared night vision goggles, condoms (to reduce the 14 percent VD casualty rate of most armies), and MRE (meals ready to eat) trays, warmed by body heat alone, to toothpaste and toilet paper.

This logistical capability of the Americans was, in the Siberians’ eyes, the real victor of Desert Storm, as the Siberians believed that, man for man, their troops, raised, born, and trained in the Arctic, were far tougher than the American and British allies. The Americans were superb at organization and improvisation, the commanding officer, Lieutenant General Dracheev, pointed out to his two-thousand-man Ratmanov garrison, and the American capability was seared into the psyches of the entire garrison. The Siberians, in their “Saddam” tunnel complex, now moved with a well-oiled efficiency, as if some vast collective unconscious had risen from within the great rock to insulate them between Ratmanov and the Smart bomb attacks.

Only in two places, the northeastern end of the island and through a clutch of radar antennae, whose bases had become dislodged before they were able to be retracted far enough, did shrapnel from the Allied bombs permeate, killing eight men and wounding a score more. Even so, the integrity of the rock proved anew the feet, grudgingly conceded by the U.S. Air Force and the pilots of the navy Tomcats and the beloved Grumman A-6E Intruders, with their eighteen-thousand-pound bomb loads coming in from Salt Lake City, that aerial bombardment, though it might cause jaw-splitting headaches, toshnota— ”nausea”— from “shock wave multiples,” and blurring of one’s vision, could not win against, or even dislodge, the deeply dug keepers in the oil-cushioned “Saddam” bunkers of Ratmanov Island.

Lieutenant General Dracheev, who knew that the sole reason for the Ratmanov garrison’s existence was to remain an immovable threat and obstacle to the Americans, obviating the need for Novosibirsk to risk precious aircraft over the strait, felt secure in his control bunker. Halfway down the island, it had been dug one hundred feet into the solid rock, three hundred feet in from the eastern cliff face.

He peered at the night sky though his infrared periscope, which could be used at either the level he was now standing, sixty feet below the surface of solid rock, or two levels further down in Control at the hundred-foot level. Seeing no sign of enemy activity and assured by his radar controllers that no air traffic could be detected in the local area of the Diomedes, Dracheev headed down toward his bunker from the first periscope level.

The concrete stairwell was watched over by a KPV Vladimirov heavy machine gun post, only part of its 135-centimeter-long barrel visible in the ball turret mounted in the door. At the machine gun the reinforced concrete stairwell took a downward-sloping U-turn to yet another closed door. Here, at the second of the three levels, another machine-gun inset had to be swung open to allow the commander and his aides into this eighty-foot level of the hundred-foot-deep bunker. The floor was a two-foot-thick antidetonator slab of reinforced concrete and high tensile steel. The next flight of stairs led to the air lock, in the event of chemical attack, outside the main command bunker at the one-hundred-foot level. All three levels were separated by at least ten feet of rock. The upper level contained a SPETS guard detachment, whose dormitories, canteen, and bunks were on the second level, which also contained all communications consoles, a conference room, and two bedrooms for Lieutenant General Dracheev and his aide, a SPETS colonel.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Arctic Front»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Arctic Front» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Arctic Front» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.