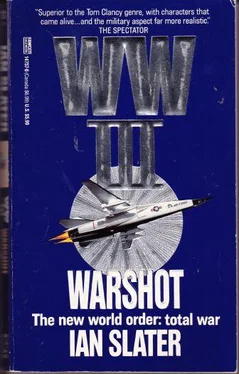

Ian Slater - Warshot

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian Slater - Warshot» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Ballantine Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Warshot

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ballantine Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- ISBN:0-449-14757-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Warshot: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Warshot»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The counterstrike: Unleash the brilliantly unorthodox American General Douglas Freeman. If this eagle can’t whip the bear and the dragon, no one can…

Warshot — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Warshot», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

With insertion by air rather than by submarine having been decided on by Freeman because of the unknown configuration of sub nets at the mouth of the Yangtze and Huangpu, Robert Brentwood felt even more that he was the odd man out among the SEALs. Though with his rank he was the “wheel”—the senior officer in charge of Operation Country Garden — he was at least ten to fifteen years older than most of the two four-man Echo One and Echo Two teams.

And there were dozens of details he had to worry about, any of which, if not attended to, could foul up the mission. Even the relatively quiet purr of the muffled thirty-five horsepower outboard engines, should they have to use them, might be picked up by river traffic, though during the bull-pen briefing board Salt Lake City, intelligence reports had assured him that the noise wouldn’t be heard amid the distinctive and unvarying two-stroke putt-putting sound of the Chinese barges. The Chinese apparently used the same engines on all their waterways. It was as if, in his free-floating anxiety before the mission, his mind, keyed for action, needed to alight on some concrete detail as a temporary way of escape, a way of filling in the time before the inevitable unknown.

But the other SEALs were giving all their attention to their weapons. In the first Pave Low, carrying Brentwood’s Echo One team, Rose was checking the number-four buckshot cartridges for his AAI — Aircraft Armaments Inc. — ”double S,” or silent shotgun. Using a plastic pusher piston, the gun could send the buckshot out at over four hundred feet a second, the shell’s expanding metal preventing any gases escaping; meaning that if the weapon had to be used, its only sound would be the soft click of the double S’s firing pin. Apart from the explosives, the remainder of the SEALs’ small but lethal arsenal included Smith & Wesson .38 pistols, fragmentation and smoke grenades, emergency flares, and in Bullfrog Brady’s Echo Two team, a Smith & Wesson Model 76 submachine gun carried by Echo Two’s radio operator. In Echo One, Robert Brentwood was also armed with a Smith & Wesson Model 76, while Diver First Class Dennison packed a Stoner MK-23 with a 150-round belt-box feed.

In Echo One’s last-minute check, Brentwood had Rose, Dennison, and Medical Corpsman Smythe — who was also Echo One’s radio operator — make sure each of the three thirty-second-fuse Claymore mines was in the semi-inflated boat, trusting that Brady was making the same equipment check aboard the Echo Two Pave Low, a quarter mile aft of them. Unconsciously, Brentwood felt for the Griptite sheath of the high-carbon steel knife strapped to his calf and for the small, pen-sized signal light. Glancing at the C-4 plastique explosive packs, he detected an odor that shouldn’t be aboard the helo. He’d ordered everyone to eat one of the regional Chinese meals before they’d taken off from the carrier. ChiComs could smell American food a hundred yards away. More than one U.S. soldier had died in Korea and ‘Nam because of that, the Americans’ red meat diet especially detectable by Asians.

“Everyone on rice and fish before we took off?”

Dennison, Rose, and Smythe all nodded affirmatively, the perfume-like smell of gum apparently coming from the chopper’s electronic warfare officer. Brentwood told him to get rid of it.

“Well, gentlemen,” Brentwood noted, to ease the tension a little, “according to my GPS here, we’re right on the money.” The handheld global positioning system, fed by satellite atomic clocks in orbit, was giving him a second-by-second readout of precisely where they were over the velvety blackness of rice fields south of Taizhou, just seventy miles east of Nanking. “We’re exactly five hundred and eighty-eight miles east sou’east of Beijing. Error factor — no more than twenty yards — in case you were wondering where you are.”

“Reminds me of a story,” said Smythe, his voice made tremulous by the rotor’s vibration. “This guy’s at an outdoor Indian convention—”

“Is he Indian?” asked Rose.

“What? Yeah, ‘course he’s Indian,” said Smythe. “Anyway, the head honcho asks him what tribe he’s from — ticking ‘em off on a clipboard, right? Indian guy says, ‘I’m a member of the Farkarwee tribe.’ Head honcho looks down, reads through the whole list from Apache to Sioux, says to the guy, ‘You sure? I can’t find the Farkarwee tribe on the list. How many are you?’

“ ‘Only me and my granddad,’ says the guy. ‘But I know we’re definitely the Farkarwee tribe.’ “

Smythe shook his head, like he was the guy with the clipboard. “Head honcho didn’t know what to do. Didn’t want to offend the guy, but he couldn’t find the tribe. Maybe it was extinct, wiped out? So he asks the guy again. Says, ‘You sure it’s the Farkarwee tribe?’

“ ‘Sure I’m sure,’ says the Indian.

“ ‘You positive?’ says the head honcho. ‘ ‘Cause it’s not on my—’

“ ‘Look,’ the Indian says, ‘there’re only two of us left, but I know we’re the Farkarwee tribe.’

“ ‘How can you be so sure?’ asked the head honcho.

“ ‘Because,’ says the Indian, ‘every mornin’ when we were comin’ across the country to this convention, my grandfather’d go out in front of the tepee, put up his hands and say, ‘Where the fark are we?’ “

Brentwood saw the cargo hold light go to red. They were five minutes from the landing zone. Once they reached it, they would rappel from the chopper down onto the muddy bank seven miles south on the river’s western bank, where the Yangtze, straightening out upstream, was at least three miles wide. A seven-mile-long, spatula-shaped island lay three-quarters of the way across from their touchdown point on the western shore. Both four-man teams and Zodiacs would be out and the chopper gone within three minutes, the men having to take out the Zodiacs semi-inflated. “Like pallbearers!” as Rose had indelicately put it during the briefing. Full inflation of the rubber boats by carbon dioxide cartridge would take place once they were outside the chopper, moments before carrying them to the riverbank.

The Pave Lows banked left to the southwest in a wide, end sweep that would be longer man a direct run in, but would keep them low over the rice fields and levees and, most importantly, clear of the three 425-foot towers situated north of the bridge.

Two minutes from the insertion point, the Paves’ pilots went from manual to hover coupler. The latter’s computer-fed data from the gyroscope inertial guidance system and altimeter automatically altered trim and yaw through rotor control to keep the chopper coming in on a steady vector low over the levees, toward the preprogrammed drop-off point by the river, now four minutes away.

The pulsating red light turned to amber.

As leader of Echo One, Brentwood, like Brady leading Echo Two, would have preferred a drop-off point closer to the bridge, and to land on the eastern, down-channel traffic side, but most of Nanking’s population lived on the eastern shore. Besides, the island would shield them from the more populated eastern bank.

Inside the cargo hold, Brentwood felt the tremulous vibration prior to the drop-off, saw the amber light switch to green.

“Go!” said the copilot, and the Pave Low’s gaping door ramp opened. Within seconds Brentwood’s Echo One and Brady’s Echo Two teams were both out of the choppers. The second Robert Brentwood touched ground, the smell of riverbank mud and human excrement from the rice fields snatched his breath away. Then his infrared goggles revealed a broad shimmering expanse that was the river, and before it a gradually sloping gray that was the riverbank. From the first step in his rubber reef walkers, which doubled as fin slippers, he could feel an icy wind moaning about his rubber suit. Through the infrared, the shimmering negativelike image that was the expanse of river became crazy-quilted, dark patches caused by gusts that had ruffled the surface and suddenly lowered the temperature of the water-air interface.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Warshot»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Warshot» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Warshot» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.