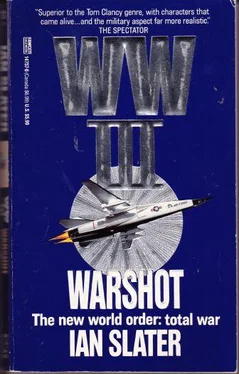

Ian Slater - Warshot

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian Slater - Warshot» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Ballantine Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Warshot

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ballantine Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- ISBN:0-449-14757-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Warshot: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Warshot»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The counterstrike: Unleash the brilliantly unorthodox American General Douglas Freeman. If this eagle can’t whip the bear and the dragon, no one can…

Warshot — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Warshot», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

One of the reasons for the Chinese reverence toward the great bridge was that during the bitter Sino-Soviet disputes of the sixties, Khrushchev had suddenly pulled out all Russian advisers, including the plans for the bridge — in effect saying to Beijing, “If you’re so damn smart, build it yourselves.” To the world’s astonishment, especially the Siberians — for whom the bridge was now so vital — the Chinese did build it themselves, producing one of the greatest engineering feats of all time. Not only did the mighty bridge, nine piers in all, support a deck with 2.8 miles of road way, but it had a railroad on a lower second deck that spanned the great river for over four miles. When Mao and his Communists crossed the river on April 23, 1949, chasing out the Nationalists, they had also, for the first time, united the two Chinas: that “cold” China of the north, the country of the “noodle eaters,” and the warmer country of “rice eaters” south of the Yangtze.

“The Nanking Bridge,” began the SEAL briefing officer without ceremony — he might as well have been talking about the Ventura Freeway—”is the largest bridge over the Yangtze. Vital link between north and south China at any time but now — with early rains flooding out the approach roads to the other crossings — this Nanking baby is their only one, especially given its rail-hauling capacity.” He switched on the projector, and Brentwood could hear the quiet whir of the air fan, which was strangely comforting, given the monumental task that eight men now realized lay before them. “Air force,” continued the briefing officer, “haven’t been able to get anywhere near it. It’s not only the lousy weather, but the AA ring around this sucker is something else. Five times denser than it ever was around Hanoi. SAM sites, ZSU AA batteries — you name it, they’ve got it — including a nifty little number they bought from Israel — the Arrow Mach Two plus. Nasty. Besides…” He dimmed the lights and focused the black-and-white blowup of a blurred satellite picture of the bridge which they used in Pearl for a scale mock-up. It always amazed Brentwood that they claimed a camera on some of the satellites in geosynchronous orbit, like the K-16, could read a newspaper in Red Square. All he could see was a black blur indicating the bridge, the latter circled in white on the slide.

“Difficult to make out with the naked eye,” conceded the briefer, as if reading Brentwood’s thoughts. “But under the magnifier, you can see the nine piers all right. Set on concrete blocks. Now, the big problem is that this was built in the heyday of Red China’s paranoia about America.”

“Had a touch of that ourselves, didn’t we?” asked Rose.

The briefing officer shrugged the comment off; his grandpa had said something about it — a Senator Joe McCartney… or something. “Yeah. Well, what you’ve got to remember is that this bridge has, like I say, nine piers, and it’s a truss bridge — that is, there are V-shaped steel supports arcing out either side from each of the nine concrete piers. These steel arcs hold up eight individual sections between the nine piers. I repeat, eight individual sections. It’s not all one span.”

Brentwood was right on it. “So even if we blow a hole in one section — if we don’t take out the whole span, they just build over the hole.”

“Right. And even if you hit the top level, there’s a second, the rail deck, underneath. So you’re going to have to knock out a pier or bring down a whole section between piers. ChiComs knew what the hell they were doing, not building it in one continuous span. They built eight of the bastards in the event of war. The problem is, in order to get enough high explosive to blow out a pier, you’d have to drill deep holes for the charges.”

“And the Commies don’t like that!” said the Bullfrog, Brady.

“Nah,” said the briefer, scrunching up his face, adopting Brady’s tone. “Make too much noise, and concrete dust might hit a sampan, get in their chop suey. Probably get Melvin Belli to sue the shit out of you.”

“That sounds fair,” said Rose.

“That’s all we need,” said Dennison, who was just coming out of a messy divorce. “More fucking lawyers!”

“What we need, gentlemen,” said the briefing officer, “is to insert you clandestinely and have you do what damage you can. Now, we can’t drill into the pier, so you’re going to have to get high enough above the pier’s waterline to attach the HE to the trusses, place the explosives near the bottom of the V-shaped steel supports where they’re embedded into the concrete. Remember, this isn’t the movies. It’s not the blast per se that’ll bring the steel supports down, but the heat generated for a second or two — just long enough to soften the steel so it’ll droop like taffy on a fork, and then the whole damn shebang’ll come tumbling down. It’s all in raising the temperature high enough to plasticize the steel for a split second or two. Failing that, go for an ‘earmuff HE charge on two piers supporting one of the spans. If you don’t get a span, they’ll just lay a few planks across the hole from a half-assed explosion, like they did on that Baghdad bridge we hit in the Iraqi War. Traffic’d be going across it within twenty-four hours. Freeman wants this sucker closed down for a week — two, if possible — and one span coming down’ll accomplish that — sever the ChiCom supply line.”

“While we’re hitting them in the north?” put in Dennison. “That’s a gamble, isn’t it? We’re in enough shit up north already — Three Corps is getting chopped to pieces. What’s going to stop Yesov long enough for Freeman to wheel his muscle south against the Siberian-ChiCom border?”

“General Freeman’s attending to that right now,” answered the briefer. “Your job will be to knock out the bridge.”

“Well, sir,” Rose said wryly, turning to Brentwood. “You were right — it’s ‘clearance’ work all right.” The others laughed, Brentwood responding in kind.

“Ah, what the hell?” he said. “Same country anyhow.”

“Okay,” said the briefer. “We can’t take you in by sub, as first hoped.” He looked at Brentwood. “That’s why you were seconded, Captain. But we’ve had to scrub that idea. ChiCom sub nets at the mouth of the Yangtze are too well placed — set just deep enough for their guided missile destroyers and gunboats to skittle over, but too shallow for any of our subs.” He turned to Brentwood. “Sorry about that, sir. We thought originally we could have you take the team in via—”

“Then I’m excused,” joked Brentwood, getting up as if to leave.

It got the biggest laugh of the day, which was just as well — the details of the task facing them were not encouraging.

Insertion would be by two Pave Low choppers, rather than one, in the event one was hit or experienced mechanical difficulties, flying low, nap of the earth, to avoid radar. They would take off from the carrier USS Salt Lake City on station 320 miles out in the South China Sea, outside the Nanking AA perimeter.

Extraction would be by the same method. If the SEALs got into difficulty, the SOS emergency code word or signature selected by Bullfrog Brady to initiate an SAS/Delta interdiction would be “Mars.” The Bullfrog had thought hard and long about the code word. While the Yangtze was a hell of a lot warmer than the Manzhouli front where the S/D team were now en route to, it was all relative. For though no ice would be on the Yangtze, it would be cold enough.

Even with the protection afforded by the trapped layer of body-heated water in the men’s rubber suits, the temperatures would be below minus forty degrees Fahrenheit. While the suits would protect a man who would otherwise freeze up in twenty-three minutes in such water, even a suit-protected swimmer working a closed-circuit UBA, such as the COBRA rebreather, could be so exhausted, his lips so cold that it would be hard to form words properly. Anything beginning with an S was particularly difficult and had in the past sounded like an F on an emergency radio band. M words were the easiest to pronounce, no matter how cold you were. In any event, the Bullfrog hoped there would be no need to use it.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Warshot»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Warshot» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Warshot» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.