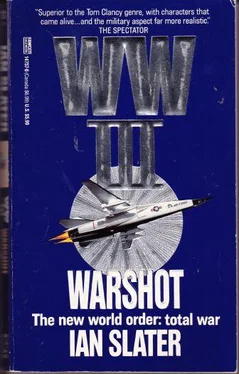

Ian Slater - Warshot

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian Slater - Warshot» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Ballantine Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Warshot

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ballantine Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- ISBN:0-449-14757-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Warshot: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Warshot»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The counterstrike: Unleash the brilliantly unorthodox American General Douglas Freeman. If this eagle can’t whip the bear and the dragon, no one can…

Warshot — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Warshot», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

“Bastards!” said Thomis, by which he meant, What the hell were the Siberians up to?

“No such luck,” Thomis heard the lieutenant reply in answer to Valdez’s hope that C Company was being bypassed by the Siberians.

Another patrol sent out earlier following the rail tracks south of C Company’s position had spotted an enemy troop concentration — at least five hundred, possibly brigade size — collecting around Kultuk. There was absolutely no doubt about it — Charlie Company was trapped between Kultuk twenty-five miles to the south and Port Baikal twenty miles to the north, and by cliffs above the artillery-ruptured ice behind them.

Suddenly someone said they could hear a chopper. “One of ours!” said Emory.

“One of theirs!” countered Thomis.

The truth was, it was impossible to tell amid the cacophony of echoes rebounding about the cliffs.

“I told you,” said Valdez. “Old Doug said he’d try to get evac through to us.”

“Old Doug’s in Khabarovsk!” said Thomis.

“Can it!” ordered Truet, who could hear them as he came down the line. But excitement was rising. Emory said it sounded like a Chinook. Throw all the crap out of it — seats, fire extinguishers, rescue winch — you could get forty or so men in a C-47, evac a whole platoon. More if you jettisoned your weapons. Truet said nothing; raising expectations was bad news if you couldn’t follow through. “Men’ll lose confidence in your leadership,” they told him at West Point, and he knew they were right.

Thomis was in the worst state, and only Emory knew what was eating away at him. Thomis and his wife had had a real dustup the night before he’d shipped out from Frisco. All the way through the tunnel they’d argued because he’d smacked young Wendy — she was ten — that morning for giving lip to her mother. He tried to make up, telling her he’d buy her something really nice for her eleventh birthday, but she’d gone into the big sulk. He’d hit her pretty hard — on the backside — and now he was thinking about how he used to kneel down, say her prayers with her. “Jesus, tender shepherd, hear me…” “Honest to God,” he’d told Emory in a quieter moment, “I’d’ve given my right hand not to have left her like that — hurting her. Her old man goes off, doesn’t come back, all she’ll remember—”

The “chunka-chunka” sound — a C-47?—grew louder, and a few of the guys started to get wound up.

“Easy now,” the sergeant told them. “Watch your perimeter.”

Thomis promised God right there and then that if he ever got out of it, he’d never hit Wendy again. Wouldn’t take any crap, but he’d never hit her — never. He could smell her warm, baby-powder smell after her bath — and her hair golden, just like her mom’s. There was another fall of snow from the trees, and he wondered whether other men in the line were making deals with the Almighty. Just get me out of this, God, and I promise…

In the dank cell, the Harbin Public Security Bureau guards had difficulty attaching the small alligator clamps to Ling’s testicles. Ling was so terrified, despite his determination not to show it, that his sheer fright and the cold combined to shrink the skin around the scrotum into a small, tight, corrugated ball with the consistency of tough old elephant skin. One of the guards jerked hard on the single rope tie that passed through Ling’s arms and around his neck. The guard had a lot of practice, having been very active in the Thirty-eighth Army’s “police action” against “antisocial elements” following Tiananmen Square in the summer of ‘89. He had tied the arms of many of the hooligans of the pro-democracy movement before they’d been executed.

“What did the Jew woman tell you?” asked the PSB interrogator.

Ling was silent, his gaze downcast, fixed on a spot of rat droppings to better focus his resistance.

“The white woman you had hiding in your house,” said the interrogator. “What did she tell you?”

Ling shook his head.

“She told you nothing?” proffered the interrogator. Ling’s head moved, but it seemed more a stiffening of his own will than an answer. Personally, the interrogator had told his superior, he’d much rather talk to the comrade — to convince Ling in a calm, logical manner that helping the Siberian Jewess against his own people was treason, an act not only against the party, but against the people. And the party loved the people. The Siberian at the consulate, however — Latov — was in a hurry to break the underground movement in Harbin, the major distribution center of food and munitions not only for Cheng’s armies fighting the Americans around Manzhouli, but for Chinese divisions spread along the Manchurian-Siberian border.

Ling didn’t feel the electric shock he’d braced himself for. Instead, the interrogator suddenly leapt out of his wooden chair with a bull-like roar, the current having short-circuited along the table. “You idiot!” he shouted, slapping one of the guards so hard that the man’s cap went flying. The other guard fumbled with the wires again while the interrogator strode angrily up and down the side of the cell farthest from the table. The shock had jolted his nerves so badly he had lit another cigarette while one was already on the go. He told the guard to turn up the amperage, and when the shock hit Ling, his scream could be heard in Stalin Park. Ling blacked out and had almost choked, the idiot guard having forgotten the tongue clamp and having turned the amperage too high.

The interrogator, his nerves rattled for the second time, reminded the guards that if they didn’t get results quickly, then someone would be taking their rice bowl to the front, and they would be thrown into the battle for A-7. American gangsters had already inflicted seventeen percent casualties on the PLA, and though they would be undoubtedly overrun, they were putting up a fierce resistance.

“Disconnect the wires,” ordered the interrogator. “You fools will kill him before he can talk.” He turned on the man at the door. “Well, just don’t stand there — go and get the boy from the hutong.” It was a thing the interrogator didn’t like to do, but now his job was much more than an internal matter of running a Democracy Movement cell to ground; it was war between the American imperialists and the People’s Army. Whatever was necessary had to be done.

While they were waiting for the boy, Ling’s wife was dragged screaming from her cell farther down the corridor. The interrogator put a cigarette into Ling’s mouth. Ling spat it out, but it was as if the interrogator didn’t see it. “I don’t dislike you, comrade,” he told Ling, his tone affecting sincerity. “I admire your courage.” Ling tried to spit at him, but it had no direction or force, merely dribbling down the faint stubble of his sallow chin.

“Now!” said the interrogator, throwing down the cigarette he’d barely started, grinding it into the time-polished floor and shaking his finger like a schoolmaster. “You have made me very angry.” A half-running, half-shuffling noise came closer to the cell, and in the dirty saffron light of the corridor Ling saw his wife, crumpled between the sweating arms of her captors.

“Put her in the next cell!” the interrogator commanded. Mrs. Ling had not looked at her husband, fearing it would weaken both their resolve, and both knowing he was a dead man.

“We’ll let them think about it for a while,” announced the interrogator, now lighting another cigarette. “Let’s see the Siberian whore.” The two guards followed him eagerly from Ling’s cell. Not only did they want to see her tortured, but if someone didn’t talk soon, they’d be in Manzhouli.

The helicopter now was high above Charlie Company in the darkness, but whether it was in front or behind them, or coming down directly overhead, was difficult to tell, the heat wash of its rotor column and engines presenting no more than a white blurred image in Thomis’s night vision goggles, icy gusts of snow stinging their faces like sand.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Warshot»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Warshot» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Warshot» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.