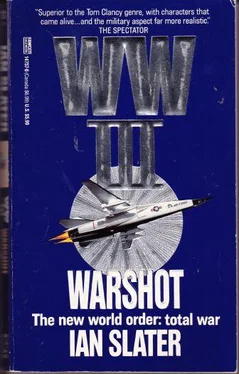

Ian Slater - Warshot

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Ian Slater - Warshot» весь текст электронной книги совершенно бесплатно (целиком полную версию без сокращений). В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 1992, ISBN: 1992, Издательство: Ballantine Books, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Warshot

- Автор:

- Издательство:Ballantine Books

- Жанр:

- Год:1992

- ISBN:0-449-14757-6

- Рейтинг книги:4 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 80

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Warshot: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Warshot»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

The counterstrike: Unleash the brilliantly unorthodox American General Douglas Freeman. If this eagle can’t whip the bear and the dragon, no one can…

Warshot — читать онлайн бесплатно полную книгу (весь текст) целиком

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Warshot», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

For the Bullfrog it was a joke, but everyone else was too tired. Including swimming time, they’d been “refreshing” themselves with all the minutiae of SEAL underwater techniques for thirty hours without a break. Still, as fatigued as he was, Brentwood recalled the Bullfrog’s earlier mention of Tarawa. It mightn’t be that the SEALs would go in during the daylight, given the chief’s mention of the PV goggles, but you’d have to be crazy to try a massive amphibious landing at night. Then again, a lot of people had thought Freeman was crazy for making a night attack on Pyongyang — until he’d pulled it off.

“Right, gentlemen,” said the chief. “Six hours sleep and we start on some lovely abutments.”

“Where?” asked Rose. “Down on Waikiki?”

“Doesn’t matter,” put in Smythe, a tall string bean of a man. “What matters is how big these mothers are, eh?” He turned to the Bullfrog. “How big are they, chiefie?”

“Mothers are big,” answered the Bullfrog truthfully. “Quartermaster’s got us down for primacord with demolition knots, with three-foot trailer cords to tie your charge to the master primacord.”

“Be using bladders?” asked Smythe.

“Yup,” confirmed the chief. “We’ll all need tits.” He was referring to Schantz bag/basket flotation packs that would take most of the weight of the explosive charges off the swimmers.

“Heavy fuckers, then?” said Reilly. “If we got Schantzes.”

“What’s the load?” added Rose. Everybody seemed to come to life with the prospect of having to suffer more than they had already. “Fifty pounds?”

“A tad more, Rosie,” said the chief, smiling. “An even hundred.”

“Jesus!” said Rose, and Smythe whistled. “We gonna refloat the Arizona?”

“We’ll do a splash-run practice tomorrow,” announced the chief. “Oh five hundred. I’ll designate flank swimmers and fuse pullers. I’ll have it ready by breakfast. Remember now, light meal, gents — don’t want anybody sinking.”

“Light meal,” quipped Dennison. “If I’m still alive.”

As they dismissed, young Rose told Robert Brentwood that the scuttlebutt around Pearl was that the Chinese had some kind of long-range rockets by some lake in far western China and that the SEALs were going to hit them.

“Well, if it’s the scuttlebutt, you can be sure it’s wrong.”

“You got it figured out, then, skipper?”

“Well, Rose,” Brentwood answered, still unused to uttering his wife’s name so far away from her, “I’ll tell you what I think, providing you keep it to yourself. No use violating need-to-know before we have to.”

“Absolutely, Captain.”

“Freeman’s going to launch an attack from Korea— across the Yellow Sea — against China’s right flank. Shantung peninsula’s my guess. Just over two hundred miles due west of Inchon.”

Rose paled. “Jesus! But… they’d chop us to pieces.”

Robert Brentwood smiled. “To do that, the ChiComs’ll have to withdraw troops from their northern borders.”

Now Rose saw the light. “Take the pressure off our guys up there.”

“Right. ‘Course, we’ll have to skedaddle on out of there once they start pouring down from the north toward the peninsula.”

“What if they don’t go for it?”

“Rose, what would you think Washington’d do if enemy troops landed on the Baja peninsula? Way I figure it, Freeman’s going to do another MacArthur — the unexpected— and we’re going in at night to take out the underwater obstacles.”

Robert Brentwood would soon be glad he hadn’t told the others of his hunch. After all, being half right doesn’t get you the kewpie doll. He was a first-rate navy man, but was talking through his hat. He was no politician, and as things stood, Washington, virtually under siege at home, had no intentions of expanding the war further by invading China. Such a move would be implicitly taken by Taiwan as the green light for it to attack, and that flash point could ignite all of Asia.

CHAPTER TWENTY-ONE

The Hutong Stank, the truck which normally collected the night carts’ cargo delayed because of the snowfall. From the tiny window, Alexsandra could see two-wheel pushcarts sitting forlornly at the end of the hutongs, abandoned. The granny brigade seemed oblivious to the stench. Much more offensive to them was the odor of their Siberian allies, many of whom were now in Harbin, frequenting the unofficial brothels that lay in the clutter of dwellings along the riverbank. Like most whites, the Siberians smelled of old, wet dog, and this morning, as the granny brigade — its three members’ red armbands vivid against the snow, their aged backs bent like vultures looking for carrion — made their way up the hutong, soldiers, both PLA and Siberians, descended to assist in the continuing search for the spy, Alexsandra Malof.

The underground had managed to hide her successfully from the granny brigade so far by keeping her in the claustrophobic room which she had since discovered lay in the rear of a small bicycle repair shop, one of those allowed under the party’s “liberalization” program. The alleyways had remained choked with snow, and piles of it were accumulating at the end of the alley, as one of the wonders of China — complete snow removal by hand — took place each day as people emerged silently from the hutong’s hovels to clear the narrow byways on command of the local committee. The grannies as usual were supervising, noting who was where, who was absent, stopping every now and then, assiduously sniffing the snow-cleansed air for the taint of wet dog.

“There’s a foreigner here!” announced the smallest of the grannies, all three dressed in identical padded and faded navy-blue Mao suits. It was an announcement clearly meant for everyone to hear, the three of them turning crooked necks, watching the two dozen or so people from their hutong silently busy with wooden push shovels and bramble brooms, the latter whisking against the bare flagstones, long crystals of ice snaking along in crazy patterns.

“There’s a foreigner here!” The brooms kept whisking, as if no one could hear her, save for an old man who, straightening up, looked about, confused, unsure of whether he’d heard a command.

The few children who had been playing quickly disappeared, swallowed by the hovels as if struck by some silent, felt message from their parents. The grannies also split up, their heads moving now with an extraordinary agility for their age as they shuffled along, noting the numbers of the houses, the smallest granny blowing her whistle shrilly.

Within minutes the street security committee arrived: three young zealots, their gender hidden under identical Mao suits, red armbands at large. They had a right to inspect each house indicated by the granny brigade. A policeman would normally accompany them — at least, this was the party regulation — but with a war going on against the American imperialists, the security committees had assumed greater authority, engendering more fear than usual in every soul in every hutong in the city of 2.7 million.

Soon an army policeman, his thick, cotton-padded, olive-green winter uniform flecked with snow, appeared, walking in from the direction of the main road.

There were no histrionics for the Lings, who ran the repair shop. Besides, there was nowhere to go. As Mr. Ling looked out the window of his cramped kitchen, he spotted a khaki truck, its tire treads choked with packed snow, PLA troops spilling out of it, a dozen heading left down the main road, another dozen or so to the right, encircling the hutong. Directly behind Ling’s repair shop lay more cluttered, snowcapped hovels leading down to the frozen river. Ling knew it was quite hopeless. He was surrounded. Besides, if there was the slightest opposition, they’d take his eight-year-old son, his only child, away as well. He went in and told Alexsandra they had discovered her. He was sorry. Their eyes met only for a moment in the grim morning light, and in that moment they both understood there was nothing they could do. To run was futile; she might as well save her strength.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

Похожие книги на «Warshot»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Warshot» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Warshot» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.