While Merrily had made three slow circuits of the church, trembling with a fearful excitement. All the time, the thoughts assembling in her head like blocks falling together, compacting, until she found she was looking at a solid, stone staircase. Leading all the way to the top of the vicarage.

Now she was walking back into the church, where Ken Thomas was coming to the end of his list. She stopped by his table.

‘Merrily Watkins,’ she said. ‘The Vicarage, Ledwardine.’

I, Merrily Rose Watkins ...

The image, from the Installation service, of an empty church. Something crawling up the stone-flagged aisle, naked and pale and wracked and twisted.

Poor Wil. You came in the evening.

When the weight was too much to bear, you came in and you locked the door behind you and shed your hated clothing and went down on the cold stones and crawled, sobbing, on hands and knees, along the aisle and up the chancel steps until the altar was above you.

And there you showed yourself to God and you called out, ‘Is this right ...IS THIS RIGHT?

‘You all right, Vicar?’ Ken Thomas said.

‘Sorry. Miles away.’

‘Been a long night,’ Ken said. He lowered his voice. ‘Bloody disgrace, her not saying a word to you. Humiliating you like that. Should’ve told you. No excuse for it. Complain, I would.’

Merrily shook her head. ‘Thanks, anyway.’ She started to walk away then went back. ‘Ken, I don’t suppose you’ll be hanging around for a while?’

‘Well, I’m supposed to call in, but most times they’ve got a job remembering who I am these days. You rather I stayed until you locked up?’

‘I think I would. We had a bit of ... vandalism, earlier.’

‘What was that, then?’

‘Well, it’s kind of complicated. If you stick around, all will be clear. Possibly.’

She moved slowly towards the chancel, past James Bull-Davies, who was still standing on his own, while Alison watched him thoughtfully, leaning over the back pew of the northern aisle. Merrily didn’t look at James. She walked halfway along the chancel, past the choir stalls, to the spot where she’d imagined the twisted, naked thing that was Wil Williams asking, Is this right?

Is it the right thing? she’d said to Lol. That’s the only question, isn’t it, when you think about it.

And it had seemed right, to find the truth and lay it out. She could have become a lawyer, working the criminal and civil courts towards a similar end. The first courtrooms had surely been constructed in imitation of churches, down to the presence of the Bible. But in church there was only one judge; the preacher in the pulpit was merely an advocate, at worst a hell-and-damnation prosecutor ...

But is it the right thing to do?

Merrily walked up to the altar and knelt and prayed for guidance.

‘If this is wrong,’ she said aloud, ‘maybe you could just strike me down.’

Everyone else seemed to have.

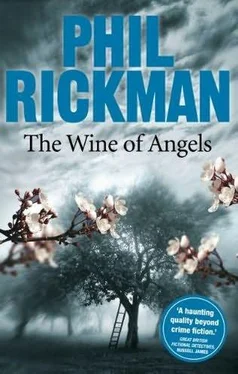

Lol looked into the box of The Wine of Angels to confirm that two bottles were indeed missing. He showed Gomer the Dancing Gates story in Mrs Leather’s book.

‘It’s obvious. She thinks she can reach Colette. She thinks Lucy wants that.’

Gomer was dubious. ‘She’d go down there on her own? To the place where ole Edgar done isself in?’

Merrily had given him a key to the vicarage and he’d been in there to make sure there was no Jane. All the way to the top floor. Nothing, except for a little black cat watching him from the hallstand.

‘It’s where they both went once. Whether she fully believes it or not she’ll think she has to try it.’

‘Right then,’ Gomer said. ‘Let’s not waste no more time.’

With a long rubber torch they’d found in the kitchen, they went the back way, over Lucy’s fence, across the old bowling green towards the orchard.

‘I don’t know what to say about this kind o’ thing,’ Gomer said. ‘When I was a boy, people laughed. When my granny was a girl, nobody laughed. What’s that? Barely a century. For hundreds of years, folk never questions there’s more in an orchard, more in a cornfield. Few decades of computers and air-conditioned tractors, even the farmers thinks it’s all balls. Sad, en’t it? Computers and air-conditioned bloody tractors.’

‘Watch yourself,’ Lol said, ‘there’s brambles all over the place.’

‘Aye.’ Gomer chuckled wryly through his ciggy. ‘Some orchard, this is. Never could figure it. They gets bugger-all off it, but they keeps it tickin’ over. Plants a couple o’ new trees every year, chops down a dead ‘un for firewood. But they won’t plough him up, start again, do it proper – superstition, I used to reckon, disguised as concern for the village heritage. But you look at Rod Powell, do he look like a superstitious man?’

‘What’s a superstitious man look like?’

‘Superstitious man looks more like you, Lol, you want the truth.’

‘Thank you, Gomer.’

‘More like you than Powell is all.’

‘Why’d he go along with the wassailing, then?’

‘No way he could refuse. Cassidy says it’s in the interests of the village, Powell’s a councillor ... Bugger me! ’

Gomer stopped in the clearing where the Apple Tree Man stood. Twin pink moons in his glasses gave him a nightmare quality.

‘I’ve fuckin’ got it, boy! Why The Wine of Angels tastes like it’s been through a horse! Listen. Cassidy, he wants to revive the ole cider industry, right? Well, that’s a tall order, given all the established firms. But if they does manage to get it off the ground, the first thing happens, see, is they get the experts in, and they looks at this lot and cracks up laughin’. Grub the bloody lot up, they’d say, not cost effective. Plough up the whole flamin’ orchard, plant some nice neat rows of dwarf trees—’

‘Could you have a dwarf Pharisees Red?’

‘Pharisees Red, Red Streak, where’s the difference? Orchardin’s moved on, it en’t what it was.’

‘So why don’t the Powells want it dug—’ Lol stared down at the base of the Apple Tree Man. ‘Oh, Jesus.’

Gomer’s grin was savage. ‘You’re thinkin’ wild at last, boy.’

When Merrily came down from the altar, Caroline Cassidy was waiting for her.

‘I don’t know why I’m still here. I don’t really know why I came. Terrence refused. He said he would prefer to wait by the phone. I almost walked out when poor Stefan made that woman tell the story about the girl who was raped and then hanged herself.’

With that story, Merrily realized now, poor Stefan was making more of a point than he imagined.

‘Knowing that these things have always happened to young girls doesn’t make it any better,’ Caroline said.

‘People got away with it then,’ Merrily said. ‘Now they seldom do.’ Perhaps, she thought, we’re here to bring peace to the spirits of old victims. Perhaps that’s the secret of restoring balance to a community.

‘They’ve been stopping motorists and showing them her photograph,’ Caroline said. ‘Now they’re even talking about some sort of reconstruction, though what use that would be in a village this size, I can’t imagine.’

‘Get it on television again.’

‘What’s the use of that? Colette’s dead. No ... No ...’ Caroline warded off Merrily’s protests with an impatient wave. ‘Don’t give me the obligatory platitudes. I only wish ... I only wish she’d been going through a nicer phase when she ...I mean, some people had a chance to grow up, to change for the better. And didn’t. Won’t be many mourners for Richard Coffey, will there, horrible man? It’s poor Stefan one feels sorry for. I would hate ... I’m sorry, don’t think I know what I’m saying.’

Читать дальше