‘Well, I would hate it if she thought I was hoping she’d, you know, intercede on my behalf, but…’ Eirion sat there, wearing his school uniform, his puppy fat, his dismal expression. ‘It’s just that Jane… Suddenly all she sees is darkness, doom, nothing amazing out there any more. Mrs Watkins has been a bit busy lately. Maybe she hasn’t noticed how bad it’s been getting.’

‘Look, I’m helping Gomer again tomorrow,’ Lol said. ‘Maybe I can call in the vicarage.’

‘I’m really sorry.’ Eirion pushed fingers through his hair and stood up. ‘Lol… look, man, I might be overreacting, all right?’

Lol looked at him, shaking his head. ‘This is Jane , Eirion.’ ‘Yes,’ Eirion agreed miserably.

The man had said, ‘She can’t be long, I suppose. Do you want to come in and wait?’ And at first Jane had been completely wrong-footed; this was hardly the kind of issue she could raise in front of both of them together, especially if their marriage was more or less on the rocks. And then she’d thought, On the other hand…

And had felt suddenly clever and strong, in a thinking-on- your-feet kind of way. In a let’s use this situation kind of way.

‘Yeah, OK,’ Jane had said coolly. ‘I suppose I could hang on for a few minutes.’ Following him into the dark-panelled hall and then into… wow…

‘I feel quite embarrassed about bringing anyone in here,’ he’d murmured. ‘I’m afraid my wife’s tastes have become a little minimalist.’

Minimalist. At once, Jane had liked the way he didn’t talk down to her. Then she learned that this was how he was: serious, saying what he meant.

Just two areas of light: the smoky greenish night in leaded windows and the glowing, crumbly fire built on the hearth – just enough to bring out this oaky feeling of age and strength. No TV or stereo on view, or anything modern or new; and the room was heavy with the oldest aroma in Herefordshire, the rich, sweet scent of apple wood.

In fact, she ought to be in two minds about all this really because, although it felt like the old Ledwardine, this was actually the new Ledwardine. Most ordinary people didn’t have the money for this sympathetic, sparing kind of conservation; they just lived around the past, with exposed wires along the beams and a Parkray in the inglenook.

Still, Jane had felt immediately at home. Enclosed. He’d taken her fleece to hang up. ‘Sorry about the temperature, but my wife absolutely refuses to have central heating in here. It would damage what she calls the monastic purity.’

‘It’s fine. It’s quite warm.’

‘It’s not terribly fine when you have to keep the damn fire going all the time,’ Gareth Box had said, sounding tired at the very thought of it, but with this sort of attractive ashiness in his voice. ‘When I’m here, I tend to build it up and keep it in all night, which I suppose is wasteful nowadays.’

‘Maybe “nowadays” isn’t what this house is about,’ Jane said smoothly. ‘You have to give it what it needs.’

‘Really.’

‘I suppose you don’t get to spend as much time here as you’d like.’

‘I think I probably do,’ he said, ‘actually. This is my wife’s house. She chose it, restored it. With her instinctive taste.’

Yes , Jane thought now, observing him over her glass, she at least has taste. Nothing minimalist about you, Mr Box.

The two Tudor-looking chairs were facing one another, either side of the fire, and were actually more comfortable than they looked, and when you sat down you felt kind of transported back . Especially with a glass of wine in your hand – red, full- bodied, naturally.

And especially when you were served by Gareth Box because – call this corny but, with his collarless white shirt and black jeans, his longish hair and his heavy, wide moustache – there really was something of the cavalier about him. Sitting down opposite Jane, pouring himself a glass of this serious wine and standing the bottle on the fairly rudimentary oak table by the side of his chair, he looked far more suited to this house than the insubstantial Jenny Driscoll ever could.

A weary cavalier, though, perhaps depleted by civil war.

‘I’m sorry.’ He held an arm towards the fire to see his watch; there was no clock in the room. ‘She really should’ve been back by now. Seems to have very little awareness of the passage of time these days.’

Jane felt his gaze on her, like a touch.

‘Look… Jane… There isn’t anything I can help you with, is there? I feel awful now, wasting your time.’

Wasting my time? Oh, I really don’t think so .

GOMER FINALLY TOOK off his cap and sat down at the refectory table. He seemed to have lost weight, the way he had just after Minnie died. His glasses were dulled.

Merrily glanced into the scullery, with Ethel floating around her shins. No sign of Jane anywhere. ‘Gone up to her apartment, I expect. Can I at least do you some toast?’

‘Tea’ll be fine, vicar.’

‘See how you feel afterwards.’ She moved around switching lamps on, then went to put the kettle on, quite glad that the kid wasn’t around. She didn’t want Gomer inhibited.

‘Oughter’ve told the cops straight away. But he was already mad as hell at me, that boy. And it was all confused, some folk near-hysterical. Bloody pandemonium.’

‘I can imagine.’

As soon as they’d left the church grounds, he’d emptied it all out for her, no flam, no excuses. He’d been mad as hell that night, see – likely with himself. Couldn’t hold himself back, even in public.

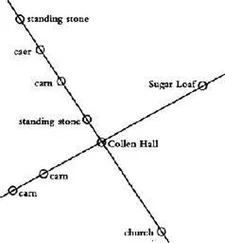

She remembered the location, under the pylon, could conjure the scene from what Lol had told her: the cops trying to conceal their panic at having lost a murderer. Local people all over the place, smudging the picture as Roddy Lodge went weaving between the flashlight beams, fast and lithe on his own territory, used to moving by night, covering a lot of ground very quickly. Easily avoiding the police, because they’d be watching all the possible exits, certainly not the pylon at the far end, fully enclosed and no way out but up.

Only Gomer, who was outside the action, having left Lol to do the spadework, had seen him go. Catching up with his enemy at the foot of the pylon. Seizing his chance, keeping his voice low.

You told ’em yet, boy?

You mad ole fuck! Gomer asking the vicar to pardon his French, but that was what Lodge had called him: Mad ole fuck .

At the time, he’d been edging Lodge back towards the giant girdery legs of the pylon, telling him, You’re goin’ down anyway. Why’n’t you just tell ’em the bloody truth ’bout what you done to my depot? What you done to Nev. Tell the truth, boy, just once in your nasty, lyin’, cheatin’ little bloody life .

Lodge’s eyes swivelling all over the place, Lodge in his bright orange overalls. But it was dark here, no coppers anywhere near, just Gomer standing his ground.

Fuckin’ kill you, ole man, you don’t get out my way.

Gomer not moving. Merrily could imagine all the scattered lights in the field gathering in his glasses as he raised himself up to his full five feet four, glaring up into Lodge’s concave face.

Oh aye? What you gonner kill me with? Got a can o’ petrol on you, is it, sonny?

Half a second for it to get through, and then Lodge had come for him, come at Gomer, rage going through his whole body – you could feel the electricity of it, Gomer would swear. And in the shock of it he’d backed away, giving just enough ground for Lodge to straighten out an arm, his open hand going flat into Gomer’s face, ramming the glasses tight into Gomer’s eyes, into his nose. And then Lodge had hissed out the typically crowing, boastful sentences that proved he’d had nothing whatsoever to do with the death of Nevin Parry.

Читать дальше