“So the ventilation shaft empties into this cavern system?” Jenny asked.

Kowalski nodded. “We should be safe once we get there.”

Tom agreed. “We call it the Crawl Space.”

2:13 P.M.

ICE STATION GRENDEL

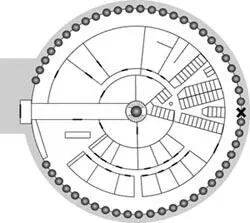

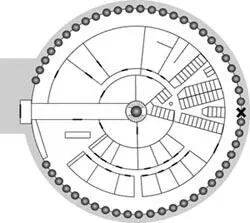

Matt fled with the others down the circular hall as it wound the circumference of this research level. To his right, he marched past the gruesome tanks, one after the other. Matt found himself counting. He was up to twenty-two.

He forced himself to stop. The tanks continued around the bend. There had to be fifty at least. He turned to the other wall of plate steel. It was interrupted by a few windows into offices, some sealed doors, and a few open hatches. He peered through one of these and spotted a hall of small barred cells. And in another, a larger barracks facility.

Here is where they must’ve housed the prisoners, Matt thought. He could only imagine the terror of these folk. Did they know their eventual fate?

Dr. Ogden trailed at Matt’s heels, while Amanda strode ahead of him. The biologist would occasionally rub at the frosted glass of a tank with the cuff of his sleeve, peer inside, and mutter.

Matt shook his head. He hadn’t the stomach for further scientific curiosity. He only wanted to get the hell out of here, back to the Alaskan backcountry, where all you had to fear was a hungry grizzly.

Behind him, a loud clang echoed from the main lab. The Russians were breaking in. After the threat from that icy voice, the group had fled, heading farther into this level.

Bratt led them. “It should be another ten yards or so.” He clutched a set of folded station plans in his hand.

Craig kept peering over the commander’s shoulder at the papers. The schematics came from a material sciences researcher from the NASA group. The scientist had mapped the entire physical plant of the station. Matt prayed the man knew his business.

Greer yelled. He was farther down the hall, scouting ahead. “Over here!” The lieutenant had dropped to one knee. A hatch lay between two tanks. Conduits and piping led out from it and spread to either side, trailing out along floorboards and ceiling to service the awful experiment.

Pearlson indicated a diagram plated to the wall above the hatch. It was the layout of this level. He tapped a large red X on the map. “You are here,” he muttered.

Matt studied the map, then glanced forward and back. They were at the midpoint of the storage hall. Halfway around this level.

Pearlson and Greer set to work unscrewing the panel, using steel scalpels. Around them, everyone carried pilfered weapons found in the labs before they fled: additional scalpels, bone saws, steel hammers, even a pair of meat hooks wielded by Washburn. Matt did not want to speculate on the surgical use of those wicked tools. He himself carried a yard-long length of steel pipe.

Matt studied their party as the sailors worked on the hatch. They had all reverted to a pack of stone-age hunter/gatherers…armed with expertly crafted surgical weapons. A strange sight.

Ogden was again rubbing at a nearby tank. The squeaking of wool on glass drew Matt’s attention. He had to resist clubbing the man with his pipe. Leave them be, he wanted to scream.

As if reading his mind, Ogden turned to him, eyes pinched. “They’re all indigenous,” he muttered. The man’s voice cracked slightly. Matt finally realized the tension wearing at the biologist, close to breaking him. He was trying to hold himself together by keeping his mind occupied. “Every one of them.”

Despite his previous objection, Matt stepped closer, brows bunched together. “Indigenous.”

“Inuit. Aleut. Eskimo. Whatever you want to call them.” Ogden waved a hand, encompassing the arc of tanks. “They’re all the same. Maybe even the same tribe.”

Matt approached the last tank the biologist had wiped. This one appeared at first empty. Then Matt looked down.

A small boy sat frozen in ice on the bottom of the tank.

Dr. Ogden was correct in his assessment. The lad was clearly Inuit. The black hair, the sharp almond eyes, the round cheekbones, even the color of his skin — though now tinged blue — all made his heritage plain.

Inuit. Jenny’s people.

Matt sank to one knee.

The boy’s eyes were closed as if in slumber, but his tiny hands were raised, pressing against the walls of his frozen prison.

Matt placed his own palm on the glass, covering the boy’s hand. Matt’s other hand clenched on the pipe he carried. What monsters could do this to a boy? The lad could be no older than eight.

A sudden flash of recognition.

He was the same age as Tyler when he died .

Matt found himself staring into that still face, but another ghost intruded: Tyler, lying on the pine table in the family cabin. His son had died in ice, too. His lips had been blue, eyes closed.

Just sleeping .

The pain of that moment ached through him. He was glad Jenny wasn’t here to see this. He prayed she was safe, but she should never see this…any of this.

“I’m sorry,” he whispered, apologizing to both boys. Tears welled in his eyes.

A hand touched his shoulder. It was Amanda. “We’ll let the world know,” she said thickly, her pronunciation further garbled by her own sorrow.

“How could this…he was only a boy. Who was watching after him?”

But Matt’s face was turned to the glass. Still, her fingers squeezed in sympathy.

Ogden stood on his other side. Eyes haggard, he was half bent studying a panel of buttons and levers. One finger traced some writing. “This is odd.”

“What?” Matt asked.

Ogden reached to a lever and pulled it down with a bit of effort. The snap was loud in the quiet hall. The panel buttons bloomed with light. The glass of the tank vibrated as some old motor caught, tripped, then began to hum.

“What did you do?” Matt blurted, offended, anger flaring.

Ogden stepped back, glancing between Matt and Amanda. “My God, it’s still operational. I didn’t think—”

A loud crash reverberated down the hall, echoing to them.

“The Russians,” Bratt said. “They’re through.”

“So are we,” Greer said with a grimace. “Almost.” Pearlson struggled with the last quarter-twist screw.

Craig stood at their backs, eyes wide and unblinking, staring between their hurried labor and the hall. The reporter held a foot-long steel bone pin, a surgical ice pick, clutched to his chest. “C’mon, already,” he moaned.

Shouts could now be heard. Footsteps on steel plate, cautious still.

“Got it!” Greer spat. He and Pearlson lifted the service hatch free.

“Everyone out!” Bratt ordered.

Craig, the closest, dove first. The others followed, flowing through the opening.

Matt, suddenly weak and tired, still knelt by the frozen boy. His hand on the glass ached from the cold of the ice inside. He felt the vibration in the glass from the buried machinery.

Amanda stepped away. “Hurry, Matt.”

He looked one more time at the boy. He felt like he was abandoning the child as he stood. His fingers lingered an extra moment, then he turned away.

Greer helped Amanda through, then waved to Matt.

He shoved over and ducked under the hatch.

Washburn was crouched on the far side. She pointed one of her steel hooks, like some Amazonian pirate, down the crawlway.

Matt followed Amanda on hands and knees, pipe under one arm. Bratt led the party, followed by Craig and the biology group. Matt hurried, making room for the others behind him: Pearlson, Greer, and Washburn.

Читать дальше