CIVILIAN

(1) Matthew Pike, an Alaska Fish and Game warden

(2) Jennifer Aratuk, sheriff for the Nunamiut and Inupiat tribes

(3) Junaquaat (John) Aratuk, retired

(4) Craig Teague, reporter for the Seattle Times

(5) Bennie and Belinda Haydon, owners of an ultralight sight-seeing company

(6) Bane, retired search-and-rescue dog, wolf/malamute cross

OMEGA RESEARCHERS

(1) Dr. Amanda Reynolds, an American engineer

(2) Dr. Oskar Willig, a Swedish oceanographer

(3) Dr. Henry Ogden, an American biologist

(4) Dr. Lee Bentley, a NASA researcher in material sciences

(5) Dr. Connor MacFerran, a Scottish geologist

(6) Dr. Erik Gustof, a Canadian meteorologist

(7) Lacy Devlin, a geology postgrad

(8) Magdalene, Antony, and Zane, biology postgrads

UNITED STATES MILITARY

(1) Gregory Perry, captain of the Polar Sentinel

(2) Roberto Bratt, lieutenant commander and XO of the Polar Sentinel

(3) Kent Reynolds, admiral and commander of the Pacific Fleet

(4) Paul Sewell, lieutenant commander and head of base security for Omega

(5) Serina Washburn, lieutenant

(6) Mitchell Greer, lieutenant

(7) Frank O’Donnell, petty officer

(8) Tom Pomautuk, ensign

(9) Joe Kowalski, seaman

(10) Doug Pearlson, seaman

(11) Ted Kanter, master sergeant, Delta Forces

(12) Edwin Wilson, command sergeant major, Delta Forces

RUSSIAN MILITARY

(1) Viktor Petkov, admiral and commander of the Russian Northern Fleet

(2) Anton Mikovsky, captain first rank of the Drakon

(3) Gregor Yanovich, diving officer and XO of the Drakon

(4) Stefan Yurgen, member of Leopard ops

ARCHIVED RECORD:

THE TORONTO DAILY STAR,

NOVEMBER 23, 1937

ESKIMO VILLAGE VANISHES!

RCMP Confirms Trapper’s Story

Special to the Star,

Lake Territory, November 23. The inspector for the Royal Canadian Mounted Police returned today to confirm the disappearance of an Eskimo village in the Northern Lakes region. Ten days ago, fur trapper Joe LaBelle contacted the RCMP to report a chilling discovery. While running a trapline, LaBelle snowshoed out to an isolated Eskimo village on the shores of Lake Anjikuni only to discover every inhabitant — man, woman, and child — had vanished from their huts and storehouses. “It was as if every one of them poor folk up and took off with no more than the shirts on their backs.”

Inspector Pierre Menard of the RCMP returned with his team’s findings today and confirmed the trapper’s story. The village had indeed been found abandoned under most strange circumstances. “In our search, we discovered undisturbed foodstuff, gear, and provisions but no sign of the villagers. Not a single footprint or track.” Even the Eskimos’ sled dogs were found buried under the snow, starved to death. But the most disturbing discovery of all was reported at the end: the Eskimos’ ancestral graves were found excavated and emptied.

The RCMP promises to continue the search, but for now the fate of the villagers remains a mystery.

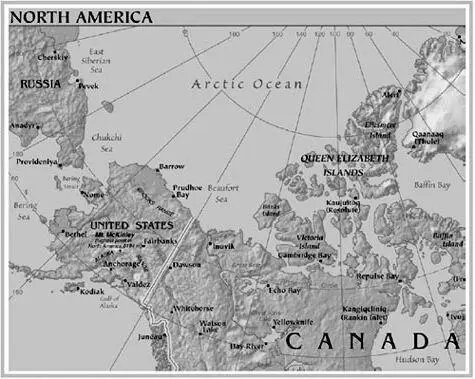

FEBRUARY 6, 11:58 A.M.

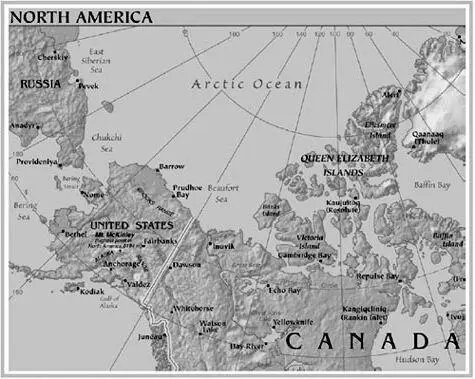

538 KILOMETERS NORTH OF ARCTIC CIRCLE

FORTY FATHOMS UNDER THE POLAR ICE CAP

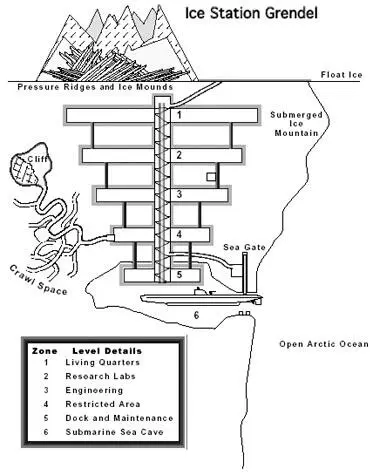

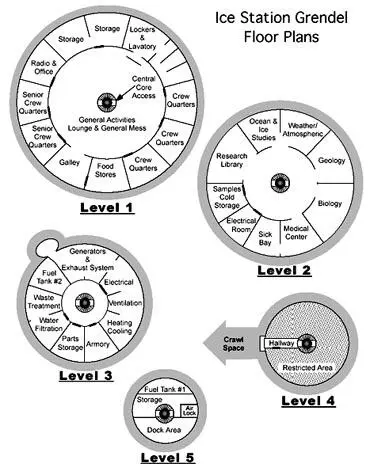

The USS Polar Sentinel was gliding through the dark ocean. The sub’s twin bronze screws churned silently, propelling the Navy’s newest research submarine under the roof of ice. The warning bells of the proximity alarms echoed down the length of the vessel.

“Sweet mother, what a monster,” the diving officer mumbled from his post, bent over a small video monitor.

Captain Gregory Perry didn’t argue with Commander Bratt’s assessment. He stood atop the control room’s periscope stand. His eyes were fixed to the scope’s optical piece as he studied the ocean beyond the sub’s double hull of titanium and plate-carbon steel. Though it was midday, it was still winter in the Arctic. It had been months since anyone had seen the sun. Around them the waters remained dark. The plane of ice overhead stretched black as far as he could see, interrupted only by occasional blue-green patches of thinner ice, filtering the scant moonlight of the surface world. The average thickness of the polar ice cap was a mere ten feet, but that did not mean the roof of their world was uniform or smooth. All around, jagged pressure ridges jutted like stalactites, some delving down eighty feet.

But none of this compared to the inverted mountain of ice that dropped into the depths of the Arctic Ocean ahead of them, a veritable Everest of ice. The sub slowly circled the peak.

“This baby must extend down a mile,” Commander Bratt continued.

“Actually one-point-four miles,” the chief of the watch reported from his wraparound station of instruments. A finger traced the video monitor of the top-sounding sonar. The high-frequency instrument was used to contour the ice.

Perry continued to observe through the periscope, trusting his own eyes versus the video monitors. He thumbed on the sub’s xenon spotlights, igniting the cliff face. Black walls glowed with hues of cobalt blue and aquamarine. The sub slowly circled its perimeter, close enough for the ice-mapping sonar to protest their proximity.

“Can someone cut those damn bells?” Perry muttered.

“Aye, sir.”

Silence settled throughout the vessel. No one spoke. The only sound was the muffled hum of the engines and the soft hiss of the oxygen generator. Like all subs, the small nuclear-powered Polar Sentinel had been designed to run silent. The research vessel was half the size of its bigger brothers. Jokingly referred to as Tadpole-class, the submarine had been miniaturized through some key advances in engineering, allowing for a smaller crew, which in turn allowed for less space needed for living quarters. Additionally, built as a pure research vessel, the submarine was emptied of all armaments to allow more room for scientific equipment and personnel. Still, despite the stripping of the sub, no one was really fooled. The Polar Sentinel was also the test platform for an upcoming generation of attack submarine: smaller, faster, deadlier.

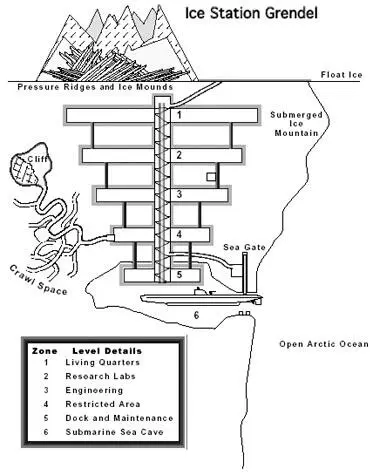

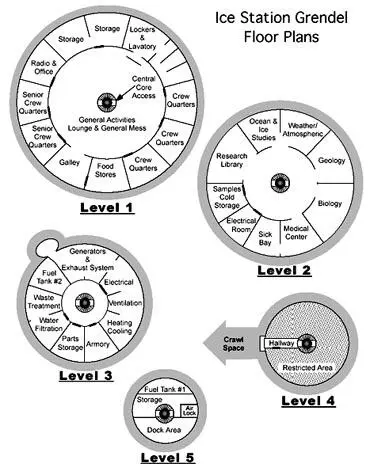

Technically still on its shakedown cruise, the sub had been assigned to the Omega Drift Station, a semipermanent U.S. research facility built atop the polar ice cap, a joint project between various government science agencies, including the National Science Foundation and the National Oceanographic and Atmospheric Administration.

The crew had spent the last week surfacing the sub through open leads between ice floes or up through thinly iced-over lakes, called polynyas. Their task was to implant meteorological equipment atop the ice for the scientific base to monitor. But an hour ago, they had come upon this inverted Everest of ice.

“That’s one hell of an iceberg,” Bratt whistled.

A new voice intruded. “The correct term is an ice island .”

Читать дальше