Bill Pronzini, Marcia Muller

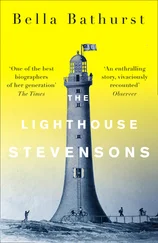

THE LIGHTHOUSE

A Novel of Terror

She ran through the night in a haze of terror.

Staggering, stumbling, losing her balance and falling sometimes because the terrain was rough and there was no light of any kind except for the bloody glow of the flames that stained the fog-streaked sky far behind her. The muscles in her legs were knotted so tightly that each new step brought a slash of pain. Her breath came in ragged, explosive pants; the thunder of blood in her ears obliterated the moaning cry of the wind. She could no longer feel the cold through the bulky sweater she wore, was no longer aware of the numbness in her face and hands. She felt only the terror, was aware only of the need to run and keep on running.

He was still behind her. Somewhere close behind her.

On foot now, just as she was; he had left the car some time ago, back when she had started across the long sloping meadow. There had been nowhere else for her to go then, no place to conceal herself: the meadow was barren, treeless. She’d looked back, seen the car skid to a stop, and he’d gotten out and raced toward her. He had almost caught her then. Almost caught her another time, too, when she’d had to climb one of the fences and a leg of her Levi’s had got hung up on a rail splinter.

If he caught her, she was sure he would kill her.

She had no idea how long she had been running. Or how far she’d come. Or how far she still had left to go. She had lost all sense of time and place. Everything was unreal, nightmarish, distorted shapes looming around her, ahead of her-all of the night twisted and grotesque and charged with menace.

She looked over her shoulder again as she ran. She couldn’t see him now; there were trees behind her, tall bushes. Above the trees, the flames licked higher, shone brighter against the dark fabric of the night.

Trees ahead of her, too, a wide grove of them. She tried to make herself run faster, to get into their thick clotted shadow; something caught at her foot, pitched her forward onto her hands and knees. She barely felt the impact, felt instead a wrenching fear that she might have turned her ankle, hurt herself so that she couldn’t run anymore. Then she was up and moving again, as if nothing had happened to interrupt her flight-and then there was a longer period of blankness, of lost time, and the next thing she knew she was in among the trees, dodging around their trunks and through a ground cover of ferns and high grass. Branches seemed to reach for her, to pluck at her clothing and her bare skin like dry, bony hands. She almost blundered into a half-hidden deadfall, veered away in time, and stumbled on.

Her foot came down on a brittle fallen limb, and it made a cracking sound as loud as a pistol shot. A thought swam out of the numbness in her mind: Hide! He’ll catch you once you’re out in the open again. Hide!

But there was no place safe enough, nowhere that he couldn’t find her. The trees grew wide apart here, and the ground cover was not dense enough for her to burrow under or behind any of it. He would hear her. She could hear him, back there somewhere-or believed she could, even above the voice of the wind and the rasp of her breathing and the stuttering beat of her heart.

Something snagged her foot again. She almost fell, caught her balance against the bole of a tree. Sweat streamed down into her eyes; she wiped it away, trying to peer ahead. And there was more lost time, and all at once she was clear of the woods and ahead of her lay another meadow, barren, with the cliffs far off on one side and the road winding emptily on the other. Everything out there lay open, naked-no cover of any kind in any direction.

She had no choice. She plunged ahead without even slowing.

It was a long time, or what she perceived as a long time, before she looked back. And he was there, just as she had known he would be, relentless and implacable, coming after her like one of the evil creatures in a Grimm’s fairy tale.

She felt herself staggering erratically, slowing down. Her wind and her strength seemed to be giving out at the same time. I can’t run much farther, she thought, and tasted the terror, and kept running.

Out of the fear and a sudden overwhelming surge of hopelessness, another thought came to her: How can this be happening? How did it all come to this?

Dear God, Jan, how did it all come to this?…

The rocky ledge runs far into the sea,

And on its outer point, some miles away,

The Lighthouse lifts its massive masonry,

A pillar of fire by night, of cloud by day.

— LONGFELLOW

Watchman, what of the night?

— OLD TESTAMENT

Her first look at the lighthouse was from a distance of almost a mile.

They jounced through a copse of pine and Douglas fir, and immediately the rutted blacktop road sloped upward to a rise. Off to the right, the land bellied out to a distant headland; beyond that she could see the ocean again, the treacherous black rocks that jutted above its surface. Back the way they’d come, the shoreline curved and gentled and formed the southern boundary of Hilliard Bay.

She didn’t see the lighthouse when they first topped the rise; she had scrunched around a little and was looking back to the north, to where buildings and fishing boats were outlined along the shore of the bay. The distance and the steely afternoon light gave them an odd, unreal look, like miniatures set out on a giant bas-relief map. But then Jan said, “Look!” and swung the station wagon off onto the verge. She twisted around again to face forward. And there it was, at a long angle to the left, perched atop a second, much narrower headland.

Jan set the parking brake and got out. “Alix, come on.” He went ahead past the front of the car and stood shading his eyes from the cloudy sun-glare.

She stepped out, stretching cramped muscles; this was the first time they’d stopped since leaving the motel in Crescent City where they had spent the night. The wind was sharp here, and cold; it made the only sound except for the faint susurration of breakers. She zipped up her jacket and went to stand next to Jan, to peer with him at the lighthouse and its outbuildings. Her first thought was: God, it looks lonely. But it was just a thought; there was nothing negative in it. If anything, she was pleased. Cape Despair. The Cape Despair Light. With names like that, she had been prepared for a desolate crag topped by an Oregon lighthouse version of Wuthering Heights. No, this didn’t seem so bad at all.

She began to view it in a different perspective, through her artist’s eye. A round whitewashed tower-vaguely phallic with its rounded red dome-poking upward out of a white, red-roofed frame building. One large outbuilding and two smaller ones that were not much more than sheds. Clouds piled up behind the tower, dirty-looking, like soiled laundry. Cliffs falling away on both sides, on the south to a narrow beach so far away it seemed hazy and indistinct. A few wind-bent trees. Cypress? Probably. Patches of green grass, dun-colored rocks, gray-bright sky. There was a melancholy aspect to the whole, a kind of primitive beauty. Nice composition, too, seen from this vantage point and with those clouds bunched up behind it. On another day like this, she thought, it would be a challenge to try capturing that melancholy aspect on canvas. The idea both pleased and surprised her, she hadn’t painted anything noncommercial in years.

“Alix? You’re not disappointed?”

“Of course not,” she said. “Do I look disappointed?”

Читать дальше