“You’re going the wrong way with that thing,” I said. “And you don’t need to run with it, anyway. I don’t know why everybody thinks that.”

“I’m sure you’re quite the expert,” she said, “but it’s late and I have to get Mike his supper.”

“Mom, let him try,” Mike said. “Please?”

She stood for a few more seconds with her head lowered and escaped locks of her hair—also sweaty—clumped against her neck. Then she sighed and held the kite out to me. Now I could read the printing on her shirt: CAMP PERRY MATCH COMPETITION (prone) 1959. The front of the kite was a lot better, and I had to laugh. It was the face of Jesus.

“Private joke,” she said. “Don’t ask.”

“Okay.”

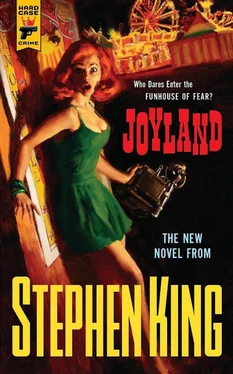

“You get one try, Mr. Joyland, and then I’m taking him in for his supper. He can’t get chilled. He was sick last year, and he still hasn’t gotten over it. He thinks he has, but he hasn’t.”

It was still at least seventy-five on the beach, but I didn’t point this out; Mom was clearly not in the mood for further contradictions. Instead I told her again that my name was Devin Jones. She raised her hands and then let them flop: Whatever you say, bub.

I looked at the boy. “Mike?”

“Yes?”

“Reel in the string. I’ll tell you when to stop.”

He did as I asked. I followed, and when I was even with where he sat, I looked at Jesus. “Are you going to fly this time, Mr. Christ?”

Mike laughed. Mom didn’t, but I thought I saw her lips twitch.

“He says he is,” I told Mike.

“Good, because—” Cough. Cough-cough-cough. She was right, he wasn’t over it. Whatever it was. “Because so far he hasn’t done anything but eat sand.”

I held the kite over my head, but facing Heaven’s Bay. I could feel the wind tug at it right away. The plastic rippled. “I’m going to let go, Mike. When I do, start reeling in the string again.”

“But it’ll just—”

“No, it won’t just. But you have to be quick and careful.” I was making it sound harder than it was, because I wanted him to feel cool and capable when the kite went up. It would, too, as long as the breeze didn’t die on us. I really hoped that wouldn’t happen, because I thought Mom had meant what she said about me getting only one chance. “The kite will rise. When it does, start paying out the twine again. Just keep it taut, okay? That means if it starts to dip, you—”

“I pull it in some more. I get it. God’s sake.”

“Okay. Ready?”

“Yeah!”

Milo sat between Mom and me, looking up at the kite.

“Okay, then. Three… two… one… lift-off.”

The kid was hunched over in his chair and the legs beneath his shorts were wasted, but there was nothing wrong with his hands and he knew how to follow orders. He started reeling in, and the kite rose at once. He began to pay the string out—at first too much, and the kite sagged, but he corrected and it started going up again. He laughed. “I can feel it! I can feel it in my hands!”

“That’s the wind you feel,” I said. “Keep going, Mike. Once it gets up a little higher, the wind will own it. Then all you have to do is not let go.”

He let out the twine and the kite climbed, first over the beach and then above the ocean, riding higher and higher into that September day’s late blue. I watched it awhile, then chanced looking at the woman. She didn’t bristle at my gaze, because she didn’t see it. All her attention was focused on her son. I don’t think I ever saw such love and such happiness on a person’s face. Because he was happy. His eyes were shining and the coughing had stopped.

“Mommy, it feels like it’s alive !”

It is, I thought, remembering how my father had taught me to fly a kite in the town park. I had been Mike’s age, but with good legs to stand on. As long as it’s up there, where it was made to be, it really is.

“Come and feel it!”

She walked up the little slope of beach to the boardwalk and stood beside him. She was looking at the kite, but her hand was stroking his cap of dark brown hair. “Are you sure, honey? It’s your kite.”

“Yeah, but you have to try it. It’s incredible!”

She took the reel, which had thinned considerably as the twine paid out and the kite rose (it was now just a black diamond, the face of Jesus no longer visible) and held it in front of her. For a moment she looked apprehensive. Then she smiled. When a gust tugged the kite, making it wag first to port and then to starboard above the incoming waves, the smile widened into a grin.

After she’d flown it for a while, Mike said: “Let him. ”

“No, that’s okay,” I said.

But she held out the reel. “We insist, Mr. Jones. You’re the flightmaster, after all.”

So I took the twine, and felt the old familiar thrill. It tugged the way a fishing-line does when a fair-sized trout has taken the hook, but the nice thing about kite-flying is nothing gets killed.

“How high will it go?” Mike asked.

“I don’t know, but maybe it shouldn’t go much higher tonight. The wind up there is stronger, and might rip it. Also, you guys need to eat.”

“Can Mr. Jones eat supper with us, Mom?”

She looked startled at the idea, and not in a good way. Still, I saw she was going to agree because I’d gotten the kite up.

“That’s okay,” I said. “I appreciate the invitation, but it was quite a day at the park. We’re battening down the hatches for winter, and I’m dirt from head to toe.”

“You can wash up in the house,” Mike said. “We’ve got, like, seventy bathrooms.”

“Michael Ross, we do not!”

“Maybe seventy-five, with a Jacuzzi in each one.” He started laughing. It was a lovely infectious sound, at least until it turned to coughing. The coughing became whooping. Then, just as Mom was starting to look really concerned (I was already there), he got it under control.

Another time,’ I said, and handed him the reel of twine. “I love your Christ-kite. Your dog ain’t bad, either.” I bent and patted Milo’s head.

“Oh… okay. Another time. But don’t wait too long, because—”

Mom interposed hastily. “Can you go to work a little earlier tomorrow, Mr. Jones?”

“Sure, I guess.”

“We could have fruit smoothies right here, if the weather’s nice. I make a mean fruit smoothie.”

I bet she did. And that way, she wouldn’t have to have a strange man in the house.

“Will you?” Mike asked. “That’d be cool.”

“I’d love to. I’ll bring a bag of pastries from Betty’s.”

“Oh, you don’t have to—” she began.

“My pleasure, ma’am.”

“Oh!” She looked startled. “I never introduced myself, did I? I’m Ann Ross.” She held out her hand.

“I’d shake it, Mrs. Ross, but I really am filthy.” I showed her my hands. “It’s probably on the kite, too.”

“You should have given Jesus a mustache!” Mike shouted, and then laughed himself into another coughing fit.

“You’re getting a little loose with the twine there, Mike,” I said. “Better reel it in.” And, as he started doing it, I gave Milo a farewell pat and started back down the beach.

“Mr. Jones,” she called.

I turned back. She was standing straight, with her chin raised. Sweat had molded the shirt to her, and she had great breasts.

“It’s Miss Ross. But since I guess we’ve now been properly introduced, why don’t you call me Annie?”

“I can do that.” I pointed at her shirt. “What’s a match competition? And why is it prone?”

“That’s when you shoot lying down,” Mike said.

“Haven’t done it in ages,” she said, in a curt tone that suggested she wanted the subject closed.

Читать дальше