Jon Stock - Dead Spy Running

Здесь есть возможность читать онлайн «Jon Stock - Dead Spy Running» — ознакомительный отрывок электронной книги совершенно бесплатно, а после прочтения отрывка купить полную версию. В некоторых случаях можно слушать аудио, скачать через торрент в формате fb2 и присутствует краткое содержание. Год выпуска: 2009, Издательство: St. Martin, Жанр: Триллер, на английском языке. Описание произведения, (предисловие) а так же отзывы посетителей доступны на портале библиотеки ЛибКат.

- Название:Dead Spy Running

- Автор:

- Издательство:St. Martin

- Жанр:

- Год:2009

- ISBN:нет данных

- Рейтинг книги:3 / 5. Голосов: 1

-

Избранное:Добавить в избранное

- Отзывы:

-

Ваша оценка:

- 60

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

Dead Spy Running: краткое содержание, описание и аннотация

Предлагаем к чтению аннотацию, описание, краткое содержание или предисловие (зависит от того, что написал сам автор книги «Dead Spy Running»). Если вы не нашли необходимую информацию о книге — напишите в комментариях, мы постараемся отыскать её.

Dead Spy Running — читать онлайн ознакомительный отрывок

Ниже представлен текст книги, разбитый по страницам. Система сохранения места последней прочитанной страницы, позволяет с удобством читать онлайн бесплатно книгу «Dead Spy Running», без необходимости каждый раз заново искать на чём Вы остановились. Поставьте закладку, и сможете в любой момент перейти на страницу, на которой закончили чтение.

Интервал:

Закладка:

He looked around the room and saw a basin in the corner. As he washed his face and glanced at himself in the mirror, drips of water falling off his unshaven chin, he was back at Stare Kiejkuty. He forced himself to think of something else. Clearly, he was the subject of a struggle between MI6 and MI5, who had handed him over to the CIA at the safe house. The arrival of Prentice at the black site meant that Fielding had not washed his hands of him altogether, which was encouraging. But Prentice had made it clear to him that MI6’s help was limited. The passport, the money (a thousand US dollars), the ticket to Delhi, his legend: that was all Fielding could do. The rest was up to him.

He lay down on the bed, feet propped up on the rucksack, and looked again at his new life: David Marlowe (same initials as his own) was taking a year out to travel around the world, starting with Europe, after graduating with a degree in modern history from Trinity College, Cambridge, just as he himself had done. MI6, Marchant knew, had arrangements with various Oxbridge colleges and redbrick universities for phone enquiries and mail. If anyone rang Trinity to ask whether a David Marlowe had studied there, the porters would find the name on a list; if anyone wrote, the post would be forwarded to Legoland via its PO box address.

He had only briefly visited Poland on his own year out, and he needed to decide on where Marlowe had gone (the legend didn’t go into detail): a week’s stay in Krakow enjoying the jazz bars, followed by a few days in Warsaw. He had planned to travel further (the Rough Guide to Poland was noticeably well thumbed), but chose to head for India, fed up with the cold weather — the talk at the hostel bar had been of little else.

He sat up and looked at the rucksack, increasingly aware of the smell rising from it. Prentice had given it to him an hour earlier at the embassy. It was bulging and well-worn, with a bright orange sleeping bag sticking out from under the top.

‘The thing’s been knocking around here for months, you might as well take it,’ Prentice had said casually.

‘Whose is it?’ Marchant asked, looking at the various badges that had been sewn on it: Paris, Prague, Munich.

‘Student, on his gap year, travelling around Europe. Died six months ago.’

‘Really?’

‘Drug overdose. We flew his body back but the rucksack never made it. Held back as evidence. The police here thought he was a mule, part of a ring. Their dogs sniffed it, found nothing. You’d better check.’

‘How old was he?’

‘Bit younger than you, same height, not as handsome, but then I only saw him on the slab.’

‘Any family?’

‘Middle-class parents, Hampshire. They’d apparently disowned him. Never asked for any personal possessions to be returned.’

Marchant started to unpack the rucksack with the caution of a customs officer. As he suspected, the clothes were rancid, revealing little about the owner except that his year of travel hadn’t taken in a visit to a launderette. He would ditch most of the fleeces and sweaters — he would only need thin clothes in India — but he would run the collarless shirts and cotton trousers through the hostel washing machine. The Rough Guide to Poland had to go, too. But the surfing bracelets would be useful once he was in India, although they weren’t half as stylish, he thought, as the ones he had once worn himself.

He looked again at his passport, hardly recognising himself in the photo: shaved head, a saffron, tie-dyed T-shirt, stud in the left ear, shell necklace slung loosely around his neck. The cobblers in G/REP, the Legoland department that specialised in forged documents, had excelled themselves. His features had been aged a little, compared to the original photo, which had been taken during his gap year in India. In real life, he knew his features had aged even more, but he was confident that he could still pass himself off as a student. Deception was as much about gait, attitude and rhythms of speech as facial appearance.

His own gap year had been a carefree time of his life. He had felt only relief when his mother had finally slipped away in his last year of school, her death allowing him to travel more freely than he might otherwise have done. For eighteen months she had suffered from cancer, but her health had started to deteriorate ten years earlier, when Sebastian had died. Severe bouts of depression blighted much of her subsequent life — and, he now realised, his own.

His father had almost sabotaged his entire year off on the night before he left. Sitting at the kitchen table of their London flat in Pimlico, he told him to let his hair down and live a bit. It could have been the kiss of death from any other father to a teenage son, but they had grown close during his mother’s illness, so his father poured him another Bruichladdich and laughed.

‘Just in case you should ever consider a career in the Service, there are only two things that make the vetters twitchy,’ his father had continued. ‘Heroin and whores.’

‘Perfect qualifications for a journalist.’

‘That’s still the thing, is it?’

‘Someone needs to expose all the Whitehall corruption,’ he grinned.

‘Your mother always wanted a doctor in the family, you know that.’ Marchant watched his father knock back his whisky, a slight tremor in his usually steady hand.

‘Because she thought Sebbie could have been saved?’

‘The doctors were very kind, said there was nothing that could have been done, but she always blamed herself for the accident.’

The years immediately after Sebastian’s death were vague now, but he remembered them as a strange time, a part of his life that floated in limbo, separate from the rest of his past. The overt kindness of so many people, more time spent with his father, his oddly withdrawn mother, who missed Sebastian terribly. His father had once hinted at some kind of mental illness, but it was the one subject he could never talk about with him. His own grieving had played out in reverse; he missed Sebastian more as each year passed.

Marchant thought again about his brother as he read through more of his own legend: the family details (English father, Irish mother), schooling, everything the same as his own life, except for the decision to travel on an Irish passport, which he knew was for operational reasons (it would draw less attention than a British one). It frustrated him that he could no longer be sure which memories were his own and which had been shaped by family albums. He remembered Sebastian playing in the orchard at Tarlton, dropping apples on their father’s sleeping head in the hammock; he could still see him sitting cross-legged with him in their room at the top of the cottage, trying to make as much noise as they could on their Indian dholak drums. There had been no photos of that.

His mother’s death was there, so too was his father’s, as well as a propensity to drink too much (a thoughtful gesture by the cobblers), but the career of David Marlowe’s father had been with the British Council. It was Marlowe’s first few years, though, that made Marchant curse them for not showing more imagination. Marlowe had also lost his brother in a car crash in Delhi, where his father had been posted. The name, Sebastian, was the same; but had Marlowe ever felt his sense of loss, the sharp jabs from the shadows that came at any time of the day or night? Marchant screwed the paper up into a tight ball. If there was one thing he could have erased from his Marlowe’s past, it would have been Sebastian’s death. But at least there would be no pretending.

He took the clothes downstairs in a plastic carrier bag and paid for some tokens and washing powder at reception. The young woman at the desk saw the bag and smiled at his domesticity. She had a flower tucked behind one ear, introduced herself as Monika, and joked that Irish travellers wore the cleanest clothes. Marchant knew conversation with anyone was a risk, but she had initiated the exchange, and it would arouse more suspicion if he kept quiet. Besides, Monika was good-looking, bohemian, early twenties — just Marlowe’s type.

Читать дальшеИнтервал:

Закладка:

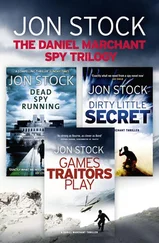

Похожие книги на «Dead Spy Running»

Представляем Вашему вниманию похожие книги на «Dead Spy Running» списком для выбора. Мы отобрали схожую по названию и смыслу литературу в надежде предоставить читателям больше вариантов отыскать новые, интересные, ещё непрочитанные произведения.

Обсуждение, отзывы о книге «Dead Spy Running» и просто собственные мнения читателей. Оставьте ваши комментарии, напишите, что Вы думаете о произведении, его смысле или главных героях. Укажите что конкретно понравилось, а что нет, и почему Вы так считаете.