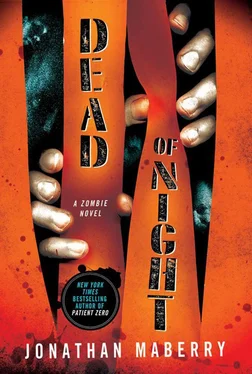

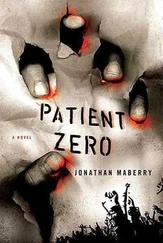

Jonathan Maberry

Dead of Night

THIS ONE IS FOR GEORGE A. ROMERO FOR RAISING THE DEAD. AND, AS ALWAYS, FOR SARA JO.

A number of good people provided invaluable information, advice, and assistance during the research and writing of this novel. In no particular order they are: Michael Sicilia, public affairs manager with the California Homeland Security Exercise and Evaluation Program; Detective Joe McKinney, San Antonio PD; filmmakers Mike Watt and Amy Lynn Best; Rodney Jones, Tim Hanner, C. J. Lyons, Scott Michaleas, Colin Madrid, Tony Faville, Laura Freed, Tonia Brown, Lisa McLean; parasitologist Carl Zimmer; ethnobotanist Dr. Wade Davis; comparative physiologist Mike Harris; Dr. John Cmar, Instructor of Medicine at The Johns Hopkins University School of Medicine and an infectious diseases specialist at Sinai Hospital of Baltimore, Maryland; Dr. Richard Tardell, specialist in emergency medicine (retired); and computer guru Jeff Strauss.

Thanks, as always, to my agent, Sara Crowe; my editor, Michael Homler; Joseph Goldschein, M. J. Rose, Don Lafferty, Doug Clegg, and Sam West-Mensch.

Thanks as well to my good friends in the Horror Writers Association, International Thriller Writers, Mystery Writers of America, and the Liars Clubs.

And thanks to the winners of the I Need to Be a Zombie in Dead of Night contests: Shane Gericke, Sheldon Higdon, Nick Pulsipher, Wrenn Simms, Kealan Patrick Burke, Michael McGrath, Andy Diviny, Jillian Weiner, Byron Rempel, Elizabeth Donald, Peggy Sullivan, and Paul Scott.

All concerns of men go wrong when they wish to cure with evil.

— Sophocles

This is how the world ends.

HARTNUP’S TRANSITION ESTATE

STEBBINS COUNTY, PENNSYLVANIA

He was sure that he was dying. It was how he imagined death would be.

Cold.

Darkness flowed slowly into the edges of everything. As if the shadows under tables and behind cabinets were leaking out to fill the room. Soft. Not painful.

That part was odd. In his dreams — and Lee Hartnup often dreamed of death — there was pain. Broken bones. Bullet wounds. Deep knife cuts.

But this … this wasn’t painful.

Not anymore. Not after that first bite.

There had been that one flash of pain, but even that was beautiful in its way. So intensely painful that it possessed purity. It was beyond anything in his personal experience, though Hartnup had imagined it so many times. With the quiet people with whom he worked. The hollow people, empty of life.

The police and the paramedics brought him demonstrations of every kind of pain. Brutalized and beaten. Crushed in car wrecks. Suicides and murders. Even the old people from the nursing homes, the ones everyone believed died peacefully in their sleep. Hartnup knew that they had experienced pain, too. For some it was the rat-hungry gnawing of cancer; for others it was the mind pain that came with having memories carved out of their brains by the ugly scalpel of Alzheimer’s. Pain for all. Pain was the coin that paid the ferryman.

Even now Hartnup smiled at that thought. It was something his father once said, back in the days when Lee Hartnup was the assistant and his father was the funeral director and mortician. Old John Hartnup had been a poetic man. Humorless but given to metaphor and simile. It was he who had started calling the bodies in their cold room the “hollow men.” Well, hollow people, to be PC. People from whom the sacred wind of life had fled through whatever crack the pain had chipped into them.

And now Hartnup felt his own sacred wind trying to blow free. The wind — the breath — was the only heat left in him. A small ball of dying air in his lungs that had nowhere to go. There wasn’t enough left of his throat for Hartnup to exhale that breath. There would be no death rattle, which amused the professional in him. He knew that some other mortician would hear it when preparing his body.

Of course, it would not be a mortician right away. First it would be a coroner. He had, after all, been murdered.

If you could call it murder.

Hartnup watched the liquid darkness fill up the room.

Was it murder?

The man … his killer … could never be charged with murder.

Could he?

If so … how?

It was a puzzle.

Hartnup wanted to cry out for warmth, but of course he could not do that. Not with what was left of his throat.

It was a shame. He was sure that he could manage at least one really good scream. Like the ones in his dreams. Most of his dreams ended in a scream. That’s what usually woke him up in the night. It’s what finally drove his wife into leaving him. She could take the fact that he worked with the dead all day, and she was sympathetic to the fact that his work gave him nightmares. But after eight years she couldn’t take the interruptions to her sleep two or three times a week. First it was earplugs, then separate rooms, and finally separate lives.

He wondered what she would think about this.

Not just his death, but his murder.

He heard a noise and wanted to turn his head. Could not.

The muscles of his neck were torn. Teeth and nails. He couldn’t feel the wounds anymore. Even the coldness was fading. His body was a remote island, separated from his mind by a million miles.

The noise again. A clatter of metal, then the singsong of tools dropping to the tiled floor. Retractors and needles and other items. Things that he wouldn’t need any longer.

Things that would be used on him in a few days.

He wondered who would prepare his body for the box? Probably that schmuck Lester Sevoy over in Bordentown.

Another crash. Then a sound. Like footsteps, but wrong somehow. Awkward. Disjointed. Like a drunk trying to stagger slowly across a barroom floor.

Lee Hartnup knew that it wasn’t a drunk, though.

He didn’t have a name for what it was.

Well … that was not exactly true.

It was a hollow man .

The room was darker now. Shadows were closing around him like a body bag being zipped up with him inside.

A simile. Dad would have liked that one.

Hartnup felt his body shivering. He felt the vibration of it but not the actual sensation. It was hard to understand. He knew that his flesh was trembling because his vision was shaking, but he felt no puckering of goose bumps on his flesh, no actual intensification of cold as his skin tried to retreat from it. And yet the vibration was there. The shaking.

He wondered at it. It was so violent that for a moment he thought that his body was going into convulsions. But that would have affected his eyesight, and he could still see as normally as the darkness allowed.

His head lolled on his ruined throat and he marveled that there was enough structural integrity left in his neck muscles to move his head so violently.

Then all at once Lee Hartnup realized what was happening.

It wasn’t a wave of cold shivers. The cold, in fact, was nearly gone. It seemed to flee as the darkness grew. It wasn’t convulsions either. The movement was not caused by any muscular action or nervous flutter anywhere in his body. This was purely external.

He was being shaken.

No … “worried” was the word. The way a terrier worries a rat.

That’s what was happening.

And yet not … This wasn’t a hunting dog trying to break the neck of a rodent. No … This was something else. Even down there in the darkness, Hartnup realized how wrong it all was. He could not feel the teeth that clamped onto him. He was beyond the sensation of pressure or pain. All that was left to him was the savage movement of his body, and the uncontrollable lolling of his head as the hollow man bit at him and tore him to pieces.

Читать дальше