“Margaret—”

“Do not go stupid on me now. What did I ask when you first came to stay with me?”

“If I wanted to fight.”

“Then fight,” Margaret said. “Play out your part. Swear you left the Butcher alive. Spare the others Braintree comes for if he is not convinced. See he gets you out before the bear is awake. Go, and someday Saint Jerome leads my Helena back home.”

I waited until out of the cottage before crying, my tears mixing with the soft rain. Margaret deserved more than to see that from me. I was halfway to the tree line when she pulled the trigger and returned her spark to Hungary.

SIDE EFFECTS

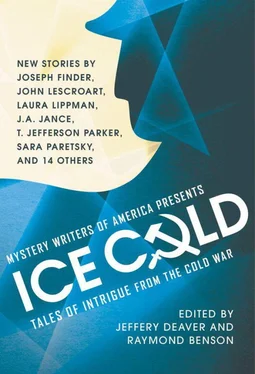

BY T. JEFFERSON PARKER

We’re down in the bomb shelter alphabetizing the canned foods so we can find what we’re looking for during an invasion or nuclear attack. Not bitchen on Labor Day weekend. The shelter is a long rectangular room with fluorescent lights, a bathroom at one end and a sink and small stove/oven at the other. Surplus military cots, blankets, pillows, and flashlights everywhere you look. No windows because it’s underground. The ceiling is low, and the lights flicker and hum and make you squint. Mom and Dad have a small record player set up down here for Tijuana Brass, Engelbert Humperdinck, and Andy Williams. If we get bombed I’ll take in my Cream and Doors. Amazing, the music old people would want to hear during a nuclear attack.

We’ve already reviewed the Batteries/Drinking Water/Perishables Rotation Schedule, which is written out on graph paper in Dad’s perfect handwriting and tacked to the corkboard below the Radiation Exposure Do’s and Don’ts. The whole family is here—Dad, Mom, Max, Marie, and me. I’m Mike, sixteen and the oldest. I can’t wait to finish up the work so I can get to 15th Street in Newport Beach, where there’s a south swell and waves running three to five feet, glassy conditions, water temp of seventy. Of course Dad has other ideas.

“Take your time and do a good job here, troops,” he says. “Chicken noodle before clam chowder and so forth, right on down the line. When this is done we’ve got some reloading to do in the gun room. The forty-five brass is really piling up! Then, the rest of Saturday is yours. But remember we’ve got the chapter meeting here tonight.”

Again, not bitchen. Fully not. The meeting is the South Orange County California chapter of the John Birch Society. Which means monthly atrocity films about the World Communist Conspiracy, programs on how to detect drug use in young people, plenty of cocktails and cigarettes, moms in short skirts, and dads with skinny ties and flat-tops. Dullsville. Me and Max steal almost-finished drinks when the grown-ups lose track of them. Which is easy when the living room is dark so they can see the atrocity films. Piled bodies, executions, maimed survivors. The speakers all agree that these things will happen here in America if we let them take our guns away. Or negotiate with the Russians. Or if we let the government put fluoride in our water. Fine, but I’m a member of the Newport Beach Bodysurfing Association, and Newport’s three-to-five and I’ve got the keys to the Country Squire.

It’s more like six to eight feet by the time we get to 15th Street that afternoon, a blow-out, the waves just mountains of chop. Some of the other club members are there. We wear white water polo caps to distinguish us in the water from nonbodysurfers, whom we call “goons.” We meet once a month and talk about contests, techniques, and trips to other breaks. I catch a right and stay tucked up high in the pocket as long as I can hang there, trimming along, palms and swim fins vibrating on the wave, which catches up and breaks over me. I could stand in that cylinder it’s so big. It’s loud , too—a full-on roar. I’m blinded by the spray, the brine grinding away under my eyelids for my short, sweet ride. Then the usual bodysurfer’s exit—a lip-launched freefall. Gravity tilts me downward but I try to maintain my elevation. Like a falling jet. I’d scream but I’ll need the air. Soon. The wave drives me straight to the bottom, where I flatten, rake my fingers into the sand and hold what’s left of my breath while the wave thunders by above me. Fireflies in my eyes. Finally I shove off and wriggle upward, break the surface in the oddly smooth and spreading wake to gasp in sudden red sunlight. Fully bitchen. So bitchen I swim back out and do it again. Several times. Later Max gets a great ride but comes up under a jellyfish and when we’re riding home his face looks like a stewed tomato. Marie, who has worked hard on her tan, thinks it’s hilarious.

When I turn onto our street I slow way down and casually look at the Lamm house. Adlyn is nowhere in sight, which is a bummer. Neither is her older brother, Larkin, which is fine with me. His van is in the driveway. The house is all concrete and glass, curvy and science fictional, nothing like the tract houses across from it, where we live. The Lamms moved in six months ago. On the last day of school I got brave enough to talk to Adlyn. Dr. Lamm is an important officer at the Tustin Naval Air Station, says Dad.

“Adlyn is nowhere, nowhere, nowhere to be found,” singsongs Marie from the back. “She’s too mature for you, Mike . You’re too chicken to call her so she has to call you .”

“Shut up, Marie.”

“My whole face is burning. Mom’s going to make me soak it in vinegar again.”

In the darkened living room the eight-millimeter projector clicks along, showing a mass grave and soldiers looking down into it. The black and white film makes all of it look even more freezing and bleak than it must have been. More doomed. Some of the soldiers still have their rifles unslung. There’s a mist in the air, but you can’t tell if it’s fog or gunpowder or the cigarette smoke in the living room.

My brother and sister and I sit three-across on the piano bench in the back. Max smells like vinegar. Mom and Dad make us sit through these things, the atrocity film and guest speaker, anyway. Mom will give us a quiz on Tuesday evening after dinner to make sure we paid attention. The next footage shows a man sitting on the edge of a big pit, stiff with bodies. He’s dressed in a beat-up suit of all things, and his hands are folded over a small suitcase on his lap, apparently something he’ll need for his coming journey. His face is sad and dirty, and he reminds me of Charlie Chaplin. A soldier steps up beside him and shoots him in the temple with a pistol, and the man slumps back against the pit side and slides in.

“Latvia? Lithuania? Estonia?” asks this month’s speaker, State Senator Brock Stile. “Do you think the World Communist Conspiracy simply stopped in Europe? How naive can you be? What do you think happened in Korea? What’s going on in Vietnam right now? Do you think the U.N. will protect us from this? I urge you to take steps to prevent this from happening here. First… become informed by joining the Society tonight. Second…”

I sip a stolen cocktail medley over fresh ice with plenty of root beer poured in. The projector clatters along, and I look at Max and Marie, the images playing on their faces, their eyes fixed to the screen. I look at Dr. Lamm, trim in his golf shirt. His mustache is brief, and he stands beside Mrs. Lamm. Mrs. Lamm is half a head taller, slender and mini-skirted, a Barbie doll with a chocolate bouffant. I spring one, hope it goes away. Why now? Why should an important part of me be outside my control?

Between Dr. and Mrs. Lamm stands their son, Larkin, a husky guy with a strong face, a cleft chin, and calm gray eyes that don’t blink. His hair is short like the grown-ups’, but he looks just a few years older than me. Smile lines at the corners of his lips. He seems amused by the film. He’s been to a few of these. He walked by the house yesterday wearing a beret and sunglasses, then came past the other way a few minutes later. Now he turns slowly and looks at Marie, then me, then back to the screen. Click-click-click-click goes the projector. Mom says Larkin attends a prestigious private liberal arts college in the Midwest, so he’s only around holidays and some weekends.

Читать дальше