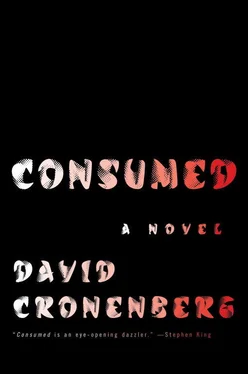

The printer was shuttling back and forth, laying down its strata of PLA on the build platform, which ratcheted lower and lower as the object, the renewable bioplastic penis, grew up like a stalagmite in a cave. It worked with measured enthusiasm, without irony, happy to be creating an extruded twisted erect penis, happy to be creating anything at all. Nathan felt weird to be identifying with the FabrikantBot, but he was. He could understand that feeling of being happy to create anything at all, to just be creative, and it suffused his trepidation about his Roiphe project, the phantom book called Consumed , which he thought maybe the FabrikantBot could print out for him. Why not? Renewable organic plastic books by the thousands.

“I would love to do the veins in blue or purple, and just the head in pink or red, but this version of FabrikantBot only does one color at a time, and you can’t combine them in one object. I’ve been doing a lot of painting, but it would be great to not have to. I’m trying to get my father to spring for the next iteration, but he’s resisting. The RepliKator 3 has dual heads and uses a hot build platform and I think you have the option of using ABS plastic and it’s more expensive. But it’s not just the money. He wants me to show him what I’ve been doing, and I don’t want to.”

“Well, he probably wouldn’t want to see Hervé’s penis, although we know he’s seen plenty of them before. Maybe just not in this context.”

“Oh, but Hervé doesn’t just send me penises.”

They left the FabrikantBot contentedly chugging away and stepped out onto the landing. Chase locked the door, then turned to the adjacent door. “That one’s my bedroom, and the next one is my bathroom, and that one”—she turned to the facing door—“the one we’re going to look at, is my art room.”

Chase flicked on the lights in a room that was a mirror image of the printing room, although this one’s dormer window was shuttered. There were two rough wooden trestle tables: a very long one the size of a picnic table, and a shorter, square table crowded with cans and tubes of paint, brushes, strips of cloth, rectangular plastic palettes with lids, painting knives, jars of water.

“See, there, I told you about the painting. You can paint directly on PLA with acrylic paint. You can sand it first too, if you want to create different textures. It would be perfect if I had a sink in here, you sometimes need water, but the bathroom’s right next door. It’s kinda messy right now.”

Chase turned away from the paints and stepped over to the big table, on which rested many large, lumpy objects covered by a bed-sized canvas sheet. Standing before it, she paused and took a deep breath—with odd reverence, thought Nathan—then leaned over and began to carefully fold back the sheet. Now gradually exposed were the thermoplastically replicated body parts of a mutilated and dismembered female human, distributed in no discernible order. They were painted crudely, but convincingly enough to induce revulsion in Nathan, reminding him of a horrifying butcher shop he had once come across in a small town in Spain. A single hacked-off breast, chunks of thigh and calf, fingers separated from one hand, a torso split into quarters, a startled head cut open and splayed with swollen tongue protruding. Almost every square inch of observable skin surface had been gouged, as though savaged by the mouths of a large school of piranhas, and each gouge had been lovingly detailed with necrotically dark-red acrylic paint.

“Hervé sent me these, piece by piece,” she said, tossing the neat bundle of the sheet under the table. “I’ve arranged them and finessed them with paint.” She turned to Nathan and leaned back against the edge of the table, hands behind her. “You know, I wanted to call this work Consumed , but my father beat me to it. Unless you can convince him to give your book another title.”

Nathan recognized the tortured body parts from the photos that Naomi had directed him to. In the aggregate, they were Célestine Arosteguy.

“YOU ACTUALLY DID IT, THEN. You cut off your wife’s breast with her consent.” Naomi was thinking journalistically and legalistically; it was an astringent approach she had to take in order to keep her balance in the thick liquid night of the late Tokyo summer. They were outside in the drab, desperate garden because the house had become too hot, too sultry, too intimate and airless. She was sitting on a lichen-stained concrete replica of a hand-cut stone bench pushed back against the far wall. The heavy-lidded orange lights built into that wall splashed her face with a medicinal glow like a disinfectant, sculpting her with deep, flushed shadows. Arosteguy paced around the garden in front of her, occasionally kicking at some piece of household garbage obscured by the darkness that rippled in cross-currents before him.

“You know, a colleague of mine—I won’t tell you who it was because you would look him up—we were at a strange karaoke event, in Paris, not here, and I was forced by circumstance to sing the song “Je t’aime… moi non plus” like Serge Gainsbourg, with the colleague singing the Jane Birkin part in falsetto. I only did it as an homage to Salvador Dalí, who is quoted in the song’s title referring to Picasso’s communism. Gainsbourg had asked Birkin to sing it so that she sounded like a little boy, and my colleague did that too, with no apparent effort. It was a moment of revelation about him that I could have lived without. And after that kitsch moment of bonding he told me that he had a savage dream, and the dream was that in a moment of passion he would cut a woman’s breast off. He was actively looking for a woman who would agree to let him do it for money, and also a doctor to guide him. He was a very fastidious and scrupulous man. I don’t know if he ever realized his desire.”

“Is that how it felt to you? Was it sexy? Was it passionate?”

“I enacted surgery. I committed surgery. And Célestine was right, as always. I wanted to keep the breast, preserve it somehow, take it to the taxidermy shop on Rue du Bac, something, even if grotesque. I couldn’t let it go. I really did feel that she was diminished by its loss, but even more selfishly, that we were diminished, our life together, our sexuality. I can’t imagine the complexity if we had had children that she had breastfed. And I said these things to her, but she wouldn’t let me keep it, and Molnár was on her side—for psychological reasons, he said, as well as health, as well as legal. Imagine being stopped on the train back to Paris… But for her it was simple: destroy it and everything inside it, like a wasp nest you’ve pulled down from the eaves with a fishing net and stuffed into a garbage bag. Burn it and the winged adults and the white grub larvae and the eggs. Burn it.”

Naomi had no doubt that Arosteguy was lying about everything (well, perhaps not some of the details of their personal life and habits), that his confession was a novel, an art project, and that he was making her his collaborator in its shaping and its dissemination. But this did not dishearten her or even challenge her sense of journalistic integrity, which, to be truthful, was always only a theoretical thing, a professional playing card, secondary to entertainment and the continuance of work, or even tertiary, with her own creative fulfillment, never spoken of, a surprising first place. If the lie was complex and enthralling—and it was, it was—then there might be a book in it, with the ever-present desire to dig for the chimeric truth driving it on, providing the suspense, and no need ever to certify that truth. She could lead her readers to wonder if the photos of Célestine’s body parts would reveal the presence of two severed breasts, thus refuting the mastectomy tale she was being told. She could press the prefect of police, M. Vernier, for this information without explaining its importance to him. She could try to examine the torso herself, the actual torso—this was an exciting thought; but had it been preserved as evidence or had it already been buried or cremated?—to see if the left breast had been surgically removed, stitched and healed, rather than brutally hacked off. The photos she had seen only revealed the torso’s left side, and a shadow obscured the wound. Was this deliberate on the part of the police? Were they even police photos? Had Arosteguy posted them himself ?

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![David Jagusson - Fesselspiele mit Meister David [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/486693/david-jagusson-fesselspiele-mit-meister-david-har-thumb.webp)