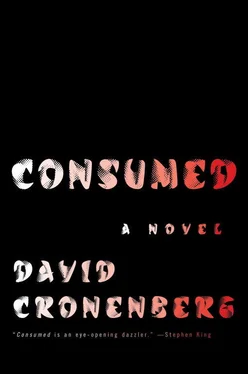

1 ...8 9 10 12 13 14 ...66 “Yes, yes. That maintenance woman… she seemed certain that Célestine Arosteguy had brain cancer.” And now Naomi could look up from fussing with her camera bag and jab back, however delicately. “Now, Dr. Trinh—I hope I’m pronouncing that correctly—Dr. Trinh, you’re not a cancer specialist, not an oncologist, for example, are you?”

The doctor took a deep breath. “What’s that pin you’re wearing? What does that designate?”

Naomi was completely thrown. Pin? Oh, yes. “This pin?” She unclipped the gold Crillon pin she had been given by her hotel contact and tossed it onto the leather writing pad on the doctor’s desk. “It’s the symbol of the Hôtel de Crillon. I’ve been staying there. It’s held on by this big round magnet. You see? They’re very nice at that hotel. Not snobbish at all.” Dr. Trinh picked it up and examined it with weird intensity. The doctor’s paranoia was suddenly exciting to Naomi, comforting rather than insulting, helping her to cycle back up. It meant that the doctor had something to hide, or at least to protect. “Were you… were you thinking it might be a microphone?”

Dr. Trinh tossed the pin back on the pad and immediately forgot it existed. “There was nothing medically wrong with Célestine Arosteguy. Nothing beyond the normal complaints of a woman of her age. I was her personal physician. I was the one who sent her to specialists when she needed them. Something like cancer… I would have known.”

Naomi desperately wanted to pull her notepad out of her bag, the one that was spiral-bound at the top, had a montage of newspaper pages decorating its cardboard cover and labelled itself “Reporter’s Notebook/Bloc de Journaliste”—naturally, Nathan had given it to her—but she could feel the fragility of the situation through her skin and didn’t dare. “What would you consider the normal complaints of a woman of her age?”

Dr. Trinh actually smiled, though there seemed to be some pain involved in the act. “Perhaps you will simply look up menopause on the internet and your question will be answered.”

A small, intimate explosion went off in Naomi’s brain, triggered by the unexpected mental juxtaposition of “menopause” and “crime,” two things she had never remotely linked before. She needed to remember this tiny epiphany somehow, and she needed to delve into the most heavy realities of menopause and womanness, a place she had never thought to go before. She generated a marker in her mind, one that would pop up whenever Célestine’s age was mentioned. “Why do you think the Arosteguys’ landlady thought that Célestine had a brain tumor? Isn’t that an odd thing for an ordinary person to just invent?”

“Have you ever met this woman, this Tretikov?”

“I’ve seen an interview with her.”

“Yes, of course.” Dr. Trinh stood up, brushing the front of her suit with her tiny hands as she did so, as though Madame Tretikov had covered her with breadcrumbs. “Yes, she’s an ordinary person who has unconsciously used the power of the internet to create a new reality concerning Madame Arosteguy. And it has caused me and my medical colleagues a lot of anguish, I can tell you.” A contemptuous snicker. “She’s the kind of superstitious old woman who believes that thinking too much, or even thinking certain thoughts, can give you brain cancer. And I want you to correct that. That is why I agreed to talk to you.” Having made her statement, this figurine of a woman sat back down and resumed exactly her former position. “The media have now accused us of negligence in our treatment of a woman who was considered a national jewel. They talk of misdiagnosis, of carelessness, of political pressure on us that forced us to ignore her deadly condition, and so on.”

“And none of that is true?”

“None of it.”

“And Célestine didn’t tell her husband that she had brain cancer, and she didn’t ask him to kill her?”

At this, Dr. Trinh produced a sad smile, and it struck Naomi as a genuine smile at last, one which illuminated the doctor’s eyes and altered her breathing, which summoned the earthy presence of Célestine Arosteguy into her fussy, controlled office. “Célestine always used to say that she was doomed and that she had a terminal illness. She said that to her students, to me, to everyone. It was not a complaint, you see. It was almost a promise. But then, anyone who read her writings deeply would know she didn’t mean anything medical.”

The smile was still on Dr. Trinh’s face as she looked down at her doll-like hands, lost in secret memories of the doomed, womanly Célestine, and Naomi found herself wanting to destroy it, to punish her for it. In particular, Naomi was annoyed with herself for not having read even a précis of the Arosteguy oeuvre and could not therefore call the doctor on this evasion. The necessary weapons, however, were close at hand. “And would she ask just anyone to kill her?” It occurred to Naomi that she had very recently fallen back on the expression “just kill me” in a conversation with Nathan in which he had again carped about his missing macro/portrait lens—the lens on her camera right now, sitting in the bag at her feet—but she doubted it would be part of Célestine’s lexicon.

“Of course not.”

“But someone did kill her. Who do you think it was?”

“I have no idea. She had many friends.”

“That surprises me. You think a friend killed her?”

“She knew many people.”

“You don’t think a stranger killed her.”

“These are things I know nothing about.”

“She would say to you, her personal physician, that she had a terminal illness, and you felt that she was being philosophical? You didn’t take it seriously?”

Dr. Trinh had been talking to her hands, but now she raised her eyes to Naomi, searching as she spoke for verifying signs of Naomi’s stupidity, her profound American ignorance. “It was an existential statement,” said Dr. Trinh, “about the death sentence we all live under. She had an affection for Schopenhauer, which led her at times into a kind of fatalistic romanticism. I tried to get her to revisit Heidegger, not so different in some ways, the Germanic ways, but at least a shift away from that sickly Asian taste for cosmic despair.” As if summoned from the ether by that last phrase, a tiny silver crucifix hanging from a bracelet around the doctor’s left wrist caught the raw daylight bouncing onto the desk from a corner mirror and caught Naomi’s eye. Naomi’s friend Yukie was also a Christian, an anomaly that was somehow a disappointment to Naomi. Shintoism, Confucianism, Taoism, Buddhism, perhaps. So much more interesting. What bracelets would they wear then? Dr. Trinh continued: “But she couldn’t get past the man’s politics, the Nazi associations, the anti-Semitism. We disagreed on that point, that a man’s politics should negate the value of his philosophy. She could not see how a separation of that kind was possible. A perfectly French attitude, of course.”

Naomi met the doctor’s eyes and her inwardly directed smile with a smile of her own, but she had no confidence that she could disguise the evidence of her immediate downward spiraling, brought about by her intense regret that she had initiated talking to another human being, live. If she had been in front of her laptop, she could google these two Germanics, get a feel for them, but in a strictly oral context she had no idea how to even spell their names, much less respond intelligently to Dr. Trinh. It was one thing to toy with Hervé, bright though he was. Nathan was the one with the classical education, or whatever you called it. He was the reader. Where was he? Naomi was struggling to keep her head above water with the doctor. A street brawl was the only way out.

Читать дальше

Конец ознакомительного отрывка

Купить книгу

![David Jagusson - Fesselspiele mit Meister David [Hardcore BDSM]](/books/486693/david-jagusson-fesselspiele-mit-meister-david-har-thumb.webp)