Yim keyed her headset mike again, just like a seal trainer at a regular zoo.

‘And these four strapping young males are red-bellied black princes. You will see dragons of three sizes here at the Great Zoo. The largest we call emperors . They are approximately the size of an airliner. Next are the kings : they are about the size of a public bus. And then there are these ones, the princes . As you can see, they are roughly the size of a horse.

‘The prince class of dragons weigh approximately one ton.’

At those words, Lucky hopped lightly on the spot, landing with a resounding boom.

The audience laughed.

‘They have a top flying speed of 160 kilometres an hour—’

Lucky took to the air, her wings spreading wide with surprising speed. She beat them powerfully and did a quick, tight loop.

‘—that’s 100 miles an hour for those not used to the metric system,’ Yim said with a smile. ‘But given the considerable exertion it takes to stay aloft, dragons can only maintain flight for short distances, a few kilometres at best. They are mainly gliders. As such, they cannot cross oceans; indeed, we have found that one of the few things they cannot stand is salt water. They hate it.’

Lucky landed again beside Yim, who flung her a fresh treat. The yellow dragon caught and swallowed it happily.

Yim said, ‘Sceptics who have doubted the existence of dragons have always questioned how something so large could possibly fly. Now we know.

‘Firstly, as you can see, dragons are not lumbering, fat-bellied beasts—they are lean and light. Secondly, like pterodactyls, they possess a peculiar kind of bone structure: their bones are hollow but with a criss-crossing matrix of high-density, low-weight keratin. This makes their bones extremely strong yet remarkably light. And lastly, their shoulder muscles and fascia—the ligaments and tendons connecting their wings to their bodies—are incredibly powerful. All of this creates an animal that can—’

‘Wait. I’m sorry. What about sight?’ CJ asked. She couldn’t help herself. ‘What sort of visual acuity do they have?’

Yim seemed momentarily vexed by the interruption, but she shifted gears smoothly. ‘Dragons nest in deep underground caves, so their eyes are well adapted to night vision. They have slit irises, like those found in cats, and a tapetum lucidum , also found in cats and other nocturnal animals. That is a reflective layer behind the retina that re-uses light.

‘Now, light is measured in lux . One lux is roughly the amount of light you get at twilight. Pure moonlight is 0.3 lux. 10 -9lux is what we would call absolute pitch darkness. Our dragons can see perfectly in 10 -9lux. Does that answer your question?’

CJ nodded.

Yim went on, clearly glad to be resuming her script. ‘Now—’

‘Can they also detect electricity?’ CJ asked quickly. This question drew odd glances from her American companions.

Yim frowned. She threw a look at Hu, who nodded.

‘Yes. Yes, they can detect electrical impulses,’ Yim said. ‘How did you know this?’

CJ nodded at the dragon. ‘See those dimples on its snout? They’re called ampullae: ampullae of Lorenzini. Sharks have them. They are a very handy evolutionary trait for a predator, a kind of sixth sense. All animals, including us, emit small electrical fields by virtue of the beating of our hearts. A wounded animal’s heart beats faster, distorting that field. A predator with ampullae, like a shark—or one of your dragons—can detect that distortion and home in on the wounded animal. It’s like being able to smell electrical energy.’

‘They are remarkable in many ways,’ Yim said diplomatically. ‘In fact,’ she added, sliding smoothly back into her patter, ‘one of the most remarkable things about them is their bite.’

Yim stepped aside, revealing a cloth-covered object on the stage behind her. She removed the cloth to reveal a brand-new bicycle.

‘No way…’ Hamish whispered. ‘Not the bike. This is so cool…’

Yim said, ‘A large dog has a bite pressure of about 330 pounds per square inch. A saltwater crocodile has a bite pressure of a whopping 5,000 pounds per square inch. A prince dragon has a bite pressure of 15,000 pounds per square inch. Allow me to demonstrate.’

One of the red-bellied blacks strode lazily forward. This dragon had large dollops of red on its head and snout. Indeed, it looked like its otherwise black head had been dipped in a bucket of red paint.

It stared at Yim with what could only be described as insolence… and didn’t do anything.

It just stood there.

And then something happened that only CJ saw: by virtue of the angle of her seat, she saw Yim produce a small yellow remote control from her belt and subtly hold it out for the dragon to see.

Seeing the yellow remote, the dragon promptly turned and, with a loud crunch, casually bit down on the bicycle. Like a soda can being crushed, the bike crumpled within its massive jaws.

The audience gasped.

‘Whoa, mama,’ Aaron Perry said aloud.

The red-faced dragon spat out the bicycle and stomped back to its place, its forked tail slinking behind it.

But all CJ could think about was the yellow remote that had prompted the creature into action. Trained animals reacted to stimuli: rewards and treats or, in the less enlightened places of the world, pain. She wondered what kind of stimulus that remote triggered and suspected that the answer was pain.

Yim bowed. ‘Thank you, ladies and gentlemen. I will hand you back to the deputy director now.’

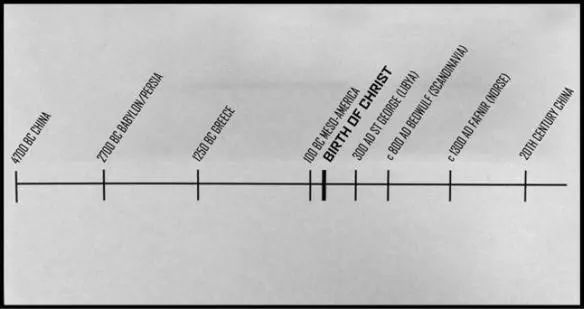

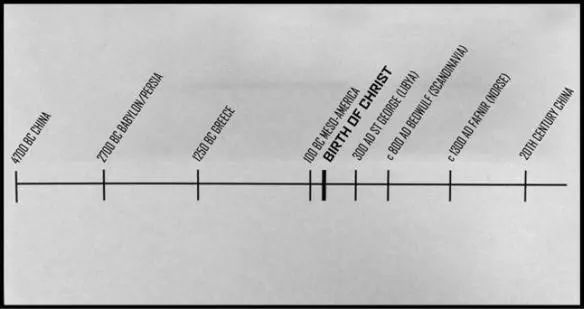

Zhang stepped forward. ‘Let me ask you this: what precisely is a dragon? Myths of gigantic winged serpents have existed for thousands of years. As with many other things, they originally appeared in China. The first Chinese dragon myth dates back to the year 4700 BC, to a statue of a dragon attributed to the Yangshao culture of that time.’

On the plasma screen behind him, a timeline appeared. The words 4700 BC CHINA popped up at the left-hand end of it.

‘The Babylonian king, Gilgamesh, fought a fierce dragon named Humbaba in the epic tale that bears his name. He lived around 2700 BC.’

2700 BC BABYLON/PERSIA appeared on the timeline.

‘The ancient Greeks spoke of Hercules fighting a dragon in order to steal the apples of the Hesperides, the eleventh of his twelve labours. Hercules is generally thought to have lived around the year 1250 BC.’

1250 BC GREECE popped up on the timeline.

‘From about 100 BC and for the next 1500 years, several Meso-American cultures including the Aztecs and the Mayans venerated a flying serpent named Quetzalcoatl.

‘And, of course, the United Kingdom has long lauded the bravery of St George who slayed a dragon not in England but in Libya around the year 300 AD.

‘In the eighth century, the Scandinavians wrote of Beowulf fighting a fire-breathing dragon and in the thirteenth century, the Vikings sang of Fafnir.’

At each mention of a historical period, the appropriate date sprang up on the timeline on the plasma screen, until it looked like this:

Hu took over. ‘There is something very curious, however, about all of these mythologies. In every single one of these myths found across the ancient world, the dragons are the same . Their features are consistent around the globe .

‘Mythical dragons are almost universally large hexapods with four walking limbs and two wings.’

At that moment, all five of the dragons on the stage opened their wings while remaining standing on their four legs.

Читать дальше