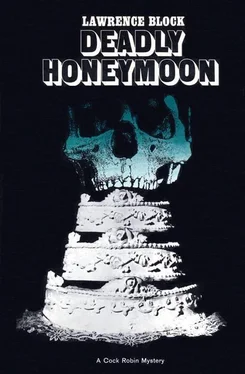

Lawrence Block

Deadly Honeymoon

Just east of the Binghamton city limits he pulled the car off the road and cut the motor. She leaned toward him and he kissed her. He said, “Good morning, Mrs. Wade.”

“Mmmm,” she said. “I think I like my new name. What are we stopping for, honey?”

“I ran out of gas.” He kissed her again. “No, they gimmicked the car. Shoes and everything. You didn’t notice?”

“No.”

He got out of the car and walked around the back. Four old shoes trailed from the license-plate mounting. On the lid of the trunk someone had painted JUST MARRIED in four-inch white letters. He got down on one knee and picked at the knots in the shoelaces. They were tight. The car door opened on her side and she got out and came back to watch him. When he looked up at her she was starting to laugh softly.

“I didn’t even notice it,” she said. “Too busy ducking rice. I’m glad we got married in church. Dave, imagine driving all through Pennsylvania with the car like that! It’s good you noticed.”

“Uh-huh. You don’t have a knife handy, do you?”

“To defend my honor? No. Let me get it. I have long fingernails.”

“Never mind.” He straightened up, the shoes in hand. He grinned at her. “Those crazy guys,” he said. “What are we supposed to do with these?”

“I don’t know.”

“I mean, is it good luck to keep them?”

“If the shoe fits—”

He laughed happily and tossed the shoes into the underbrush at the side of the road. He unlocked the trunk, hauled out a rag, and wiped at the paint on the trunk lid. It wouldn’t come off. There was an extra can of gasoline in the trunk, and he uncapped it and soaked the rag with gas. This time the paint came off easily. He wiped the trunk lid dry with a clean rag to protect the car’s finish, then tossed both rags off to the side of the road and slammed the trunk shut.

She said, “I didn’t know you were a litterbug.”

“You can’t carry them in the trunk, not soaked with gas. They could start a fire.”

“That’s grounds for an annulment, you know.”

“Starting a fire?”

“Concealing the fact that you’re a litterbug.”

“Want an annulment?”

“God, no,” she said.

She had changed from her wedding dress to a lime-green sheath that was snug on her big body. Her hair was blond, shoulder length, worn pageboy style with the ends curled under. Her eyes were large, and just a shade deeper in color than the dress. He looked at her and thought how very beautiful she was. He took a step toward her, not even conscious of his own movement

“Dave, we’d better get going.”

“Mmmm.”

“We’ve got three weeks. We waited this long, we can wait two more hours. And this is an awfully public place, isn’t it?”

Her tone was not quite as light as her words. He turned from her. Cars passed them on the highway. He grinned suddenly and got back into the car. She got in on her side and sat next to him, close to him. He turned the key in the ignition and started the car and pulled back onto the road.

From Binghamton they rode south on 81, the new Penn-Can Highway. Jill had a state map spread open on her lap and she studied it from time to time but it was hardly necessary. He just kept the car on the road and held the speed steady between sixty and sixty-five. The car was a middleweight Ford, the Fairlane, last year’s model. It was the second week in September now and the car had a shade less than fifteen thousand miles on it.

They crossed the Pennsylvania state line a few minutes after noon. At twelve-thirty they left Route 81 at a town called Lenox and cut southeast on 106 through Carbondale and Honesdale. The new road was narrower, a two-laner that zigzagged across the hills. They pulled into an Esso station in Honesdale and Jill had a chicken sandwich at a diner two doors down from the station. He had a Coke and left half of it.

A few miles further on, at Indian Orchard, they left 106 and continued south on U.S. 6. They were at Pomquit by a quarter to two. Pomquit was at the northern tip of Lake Wallenpaupack, and their lodge was on the western rim of the lake, half a dozen miles south of the town. They found it without stopping for directions. The lodge had a private road. They followed its curves through a thick stand of white pine and parked in front of a large white Victorian house bounded on three sides by a huge porch. They could see the lake from where the car was parked. The water was very still, very blue.

Inside, in the office, a gray-haired woman sat behind a desk drinking whiskey and water. She looked up at them, and Dave told her his name. The woman shuffled through a stack of four-by-six file cards and found their reservation.

“Wade, David. You wanted a cabin, is that right?”

“That’s right.”

“Honeymooners, I guess, and I don’t blame you. Wanting a cabin, that is. Rooms in the lodge are nice but you don’t get the privacy here you would be getting in a cabin. It’s an old house. Sounds carry. And privacy is important, God knows. On a honeymoon.”

Jill was not blushing. The woman said, “You picked a good time of the year now. What with the lake and the mountains it stays pretty cool here most of the time, but this year July and August got pretty hot, pretty hot. And on a honeymoon you don’t want it to be too warm. But it’s cooled off now.”

She passed the card to him. On a dotted line across the bottom he wrote, “Mr. and Mrs. David Wade,” writing the double signature with an odd combination of pride and embarrassment. The woman filed the card away without looking at it. She gave him a key and offered halfheartedly to show them where the cabin was. He said he thought they could find it themselves. She told him how to get there, what path to take. They went back to the car and drove along a one-lane path that skirted the edge of the lake. Their cabin was the fourth one down. He parked the Ford alongside the cabin and got out of the car.

Their suitcases — two pieces, matching, a gift from an aunt and uncle of his — were in the back seat. He carried them up onto the cabin’s small porch, set them down, unlocked the door, carried them inside. She waited outside, and he came back for her and grinned at her.

“I’m waiting,” she said.

He lifted her easily and carried her over the threshold, crossed the room, set her down gently on the edge of the double bed. “I should have married a little girl,” he said.

“You like little girls?”

“I like big blondes the best. But little girls are easier to carry.”

“Oh, they are?”

“It seems likely, doesn’t it?”

“Ever carry any?”

“Never.”

“Liar,” she said. Then, “That drunken old woman has a dirty mind.”

“She wasn’t drunk, just drinking. And her mind’s not dirty.”

“What is it?”

“Realistic.”

“Lecher.”

“Uh-huh.”

He looked at her, sitting on the edge of the bed, their bed. She was twenty-four, two years younger than he was, and no man had ever made love to her. He was surprised how glad he was of this. Before they met he had always felt that it wouldn’t matter to him what any woman of his had done with other men before their marriage, but now he knew that he had been wrong, that he did care, that he was glad no one had ever possessed her. And that they had waited. Their first time would be now, here, together, and after the wedding.

He sat down next to her. She turned toward him and he kissed her, and she made a purring sound and came up close against him. He felt the sweet and certain pressure of her body against his.

Читать дальше