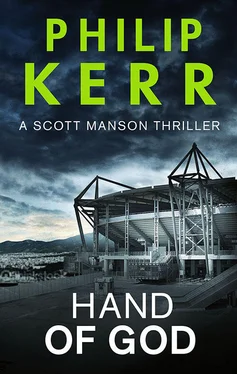

Naturally the team were all banned from heading into Athens or Glyfada to explore the city’s night life. And I’d slipped the guys manning the hotel security barrier some cash to make sure that not one female was allowed to come and visit any of the team. But before dinner I took Bekim Develi and Gary Ferguson into Piraeus where a press conference had been arranged in the media centre at the Karaiskakis Stadium. At first most of the difficult questions came from the English press which was not so surprising after the 3–1 defeat at Leicester; then the Greeks chipped in with their own agenda and the situation became a little more complicated when someone asked why Germany seemed to have it in for Greece.

‘What do you mean?’

‘Why do the Germans hate us?’

Choosing to ignore the behaviour of the Greek football fans towards the lads in Hertha FC, I said that I didn’t think it was true that Germans hated Greeks.

‘On the contrary,’ I added. ‘I have lots of German friends who love Greece.’

‘Then why are the Germans so hell-bent on crucifying us for a loan from the European Central bank? We’re on our knees already. But now they seem to want us to crawl on our bellies for the central bank’s loan package.’

I shook my head and said that I wasn’t in Piraeus to answer questions about politics and ducking an honest answer like that would probably have been fine. But then Bekim — Russian-bred, but born in Turkey, the ancient enemy of Greece — jumped in and things really deteriorated when he proceeded to make some less than diplomatic remarks about public spending and how perhaps Greece really didn’t need to have the largest army in Europe. The fact that he was speaking in fluent Greek only made things worse because we could hardly spin what he said and blame his answer on Ellie, our translator. Asked if Bekim was worried about a big demonstration planned for the night of the game outside the parliament, Bekim said it was about time some of the demonstrators put their energies into digging Greece out of the hole it was in; better still, they could start cleaning the city which, in his opinion, badly needed some TLC.

‘You’ve been living beyond your means for almost twenty years,’ he added, in English, for the benefit of our newspapers. ‘It’s about time you paid your bill.’

Several Greek reporters stood up and angrily denounced Bekim; and at this point Ellie advised that it might be best if we cut short the conference.

In the car back to the hotel I cursed myself for bringing Bekim to the press conference in the first place.

‘Once was unfortunate,’ I said. ‘But twice looks like downright fucking carelessness on my part.’

‘Sorry, boss,’ he said. ‘I didn’t mean to cause you any problems.’

‘What devil possessed you?’ I asked. ‘Christ, their fans are bad enough when it’s a friendly. You’ve made sure that tomorrow’s going to be extra rough.’

‘It was going to be rough anyway,’ he insisted. ‘You know that and I know that. Their supporters are bastards and nothing I said is going to make the way they behave any worse. And look, I didn’t tell them anything they don’t already know.’

‘We’re a football team,’ I said, ‘not a lobby group. Not content with pissing off the Russians when we were in Russia, you now seem to have managed to do the same with the Greeks. What is it with you?’

‘I love this country,’ he said. ‘I hate seeing what’s happening here. Greece is such a beautiful country, and it’s getting fucked in the ass by a bunch of anarchists and communists.’

He shrugged and looked out of the window at the graffiti-covered walls of the streets we were driving through, the many abandoned shops and offices, the piles of uncollected rubbish, the potholed roads, the beggars and the squeegee guys at the traffic lights and on the grass verges at the roadsides. Greece might have been a beautiful country but Athens was ugly.

‘I love it,’ he whispered. ‘I really do.’

‘Fuckin’ beats me why,’ said Gary. ‘Look at the state of it. Full of fuckin’ jakey bastards and spongers on the social. I’d never have believed it if I hadn’t seen it with my own eyes. Christ, I’ve seen some fucking squallies in my time. But Athens — Jesus, Bekim. Call this a capital city? I reckon Toxteth is in a better state than fucking Athens.’

‘Hey, boss.’ Bekim laughed. ‘I’ve got a good idea. After the match, why don’t you let Gary do the press conference, on his own.’

The following morning, before breakfast and while the temperatures were still in the low twenties, we had a light training session. Apilion was located in Koropi, a twenty-minute drive north from the hotel, and on a wide expanse of very rural land at the foot of Mount Hymettus which towers over three thousand feet over the eastern boundary of the city of Athens. In antiquity there was a sanctuary to Zeus on the summit; these days there’s just a television transmitter, a military base and a view of Athens that’s only beaten by the one out of a passenger jet’s window.

A green flag with a white shamrock declared that Apilion was the training ground of Panathinaikos FC. Surrounded with olive and almond trees, fig-bearing cacti, wild orchids and flocks of ragged sheep and goats, the air was clear and clean after the congested atmosphere of Piraeus and downtown Athens. From time to time one of the local farmers fired a gun at some birds, scattering them to the wind like a handful of seeds and startling our more metropolitan-minded players. In spite of that and the presence of several journalists camped alongside the carefully screened perimeter fence, Apilion felt like an oasis of calm. Nothing was too much trouble for the people from Panathinaikos; as the other half of the city’s Old Firm all they cared about was that they might assist us in sticking it to their oldest rival, Olympiacos. Football is like that. Your enemy is my friend. It’s not enough that your own team succeeds; any victory is always enhanced by a rival’s failure, no matter who they’re playing. Panathinaikos would have supported a team of Waffen-SS if they beat the red and white of Olympiacos.

‘Fucking hell,’ exclaimed Simon Page, staring up at the flag as we got off the bus. ‘Are we in bloody Ireland, or what?’ He clapped his hands and shouted at the players. ‘Hurry up and get on that training ground, and watch where you’re putting your feet in case you tread on a four-leaf clover. I’ve a feeling we’re going to need all the luck we can get here.’

I could hardly argue with him since our new team doctor, O’Hara, was returning to London after his wife had been taken ill. Antonis Venizelos, our liaison from Panathinaikos, was still trying to find us a replacement doctor in case of emergency.

‘The doctors’ strike doesn’t make this easy,’ he explained a little later on. ‘Even doctors who don’t work in the public sector are reluctant to work today. Operations have been cancelled. Patients sent home. But don’t worry, Mr Manson. The Karaiskakis Stadium is right next to the Metropolitan private hospital. Even though it is in Piraeus this is a very good hospital.’

He lit a menthol cigarette with the hairiest hands I’d ever seen and stared up at Mount Hymettus.

‘I have some other news that might have an important bearing on the game.’

‘Oh? What’s that?’

‘I just heard on the telephone,’ he said. ‘The Olympiacos team were paid their wages today, and in full. This will put them in a very good mood. So tonight I think they will try very hard.’

‘When do they normally get paid?’

‘I mean that it might be two or three months since those American bastards last got their wages.’

Читать дальше