“If you do, Mr. Kling, I wish you’d say so.”

“I don’t think you had anything to do with this burglary or with any of the others. No, Mr. Coe.”

“Good,” Coe said. He rose, opened the refrigerator, and said, “Would you care for another beer?”

“Thank you, I’ve got to be going.”

“It’s been nice having you visit,” Coe said.

The call from Joseph Angieri came to the squadroom at close to six o’clock that evening, just as Kling was preparing to go home.

“Mr. Kling,” he said, “we found the cat.”

“I beg your pardon?” Kling said.

“The kitten. You said your man always left a...”

“Yes, yes,” Kling said. “Where’d you find it?”

“Behind the dresser. Dead. Tiny little thing, gray and white. Must have fallen off and banged its head.” Angieri paused. “Do you want me to keep it for you?”

“No, I don’t think so.”

“What should I do with it?” Angieri asked.

“Well... dispose of it,” Kling said.

“Just throw it in the garbage?”

“I suppose so.”

“Maybe I’ll take it down and bury it in the park.”

“Whatever you prefer, Mr. Angieri.”

“Tiny little thing,” Angieri said. “You know, I happened to remember something after you left.”

“What’s that?”

“The lock on the front door. We had it changed just before we left for Jamaica. Because of all the burglaries on the block, figured we’d better change the lock. If somebody got in here with a key ...”

“Yes, Mr. Angieri, I follow you,” Kling said. “What’s the locksmith’s name?”

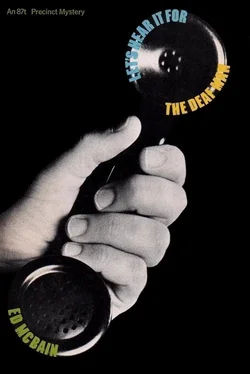

Detective Steve Carella was a tall man with the body and walk of a trained athlete. His eyes were brown, slanting peculiarly downward in an angular face, giving him an oriental appearance that was completely at odds with his Italian background. The downward tilt of the eyes also make him look a trifle mournful at times, again in contradiction to his basically optimistic outlook. He glided toward the ringing telephone now like an outfielder moving up to an easy pop fly, lifted the receiver, sat on the edge of the desk in one fluid motion, and said, “87th Squad, Carella here.”

“Have you paid your income tax, Detective Carella?”

This was Friday morning, the sixteenth of April, and Carella had mailed his income tax return on the ninth, a full six days before the deadline. But even though he suspected the caller was Sam Grossman at the lab, or Rollie Chabrier in the D.A.’s office (both of whom were fond of little telephone gags), he nonetheless felt the normal dread of any American citizen when confronted with a voice supposedly originating in the offices of the Internal Revenue Service.

“Yes, I have,” he said, carrying it off rather well, he thought. “Who’s this, please?”

“No one remembers me anymore,” the voice said dolefully. “I’m beginning to feel neglected.”

“Oh,” Carella said. “It’s you.”

“Ahh, yes, it’s me.”

“Detective Meyer mentioned that you’d called. How are you?” Carella said chattily, and signaled to Hal Willis across the room. Willis looked at him in puzzlement. Carella twirled his forefinger as though dialing a phone. Willis nodded, and immediately called the Security Office at the telephone company to ask for a trace on Carella’s line, the Frederick 7-8025 extension.

“I’m all right now,” the voice said. “I got shot a while back, though. Did you know that, Detective Carella?”

“Yes, I know that.”

“In a tailor shop. On Culver Avenue.”

“Yes.”

“In fact, if I recall correctly, you’re the man who shot me, Detective Carella.”

“Yes, that’s my recollection, too.” Carella looked at Willis and raised his eyebrows inquisitively. Willis nodded and made an encouraging hand gesture — keep him talking .

“Quite painful,” the Deaf Man said.

“Yes, getting shot can be painful.”

“But then, you’ve been shot, too.”

“I have indeed.”

“In fact, if I recall correctly, I’m the man who shot you .”

“With a shotgun, wasn’t it?”

“Which makes us even, I suppose.”

“Not quite. Getting shot with a shotgun is more painful than getting shot with a pistol.”

“Are you trying to trace this call, Detective Carella?”

“How could I? I’m all alone up here.”

“I think you’re lying,” the Deaf Man said, and hung up.

“Get anything?” Carella asked Willis.

“Miss Sullivan?” Willis said into the phone. He listened, shook his head, said, “Thanks for trying,” and then hung up. “When’s the last time we successfully traced a telephone call?” he asked Carella. He was a short man (the shortest on the squad, in fact, having barely cleared the Department’s 5'8" minimum height requirement), with slender hands and the alert brown eyes of a frisky terrier. He walked toward Carella’s desk with a bouncing stride, as though he were wearing sneakers.

“He’ll call back,” Carella said.

“You sounded like two old buddies chatting,” Willis said.

“In a sense, we are old buddies.”

“What do you want me to do if he calls again? Go through the nonsense?”

“No, he’s hip to it. He’ll never stay on the line more than a few minutes.”

“What the hell does he want?” Willis asked.

“Who knows?” Carella answered, and thought about what he’d said just a few moments before. In a sense, we are old buddies .

He had, he realized, stopped considering the Deaf Man a deadly adversary, and he wondered now how much this had to do with the fact that his wife, Teddy, was a deaf mute. Oddly, he never thought of her as such — except when the Deaf Man put in an appearance. There had never been anything resembling a lack of communication in his relationship with Teddy; her eyes were her ears, and her hands spoke volumes. Teddy was capable of screaming down the roof in pantomime and dismissing his own angry response by simply closing her eyes. Her eyes were brown, almost as dark as her black hair. She watched him intently with those eyes, watched his lips, watched his hands as they moved in the alphabet she had taught him, and which he spoke fluently and with a personality distinctly his own. She was beautiful and passionate and responsive and smart as hell. She was also a deaf mute. But he equated this with the lacy black butterfly she’d had tattooed on her right shoulder more years ago than he could recall; they were both superficial aspects of the woman he loved.

He had once hated the Deaf Man. He no longer did. He had once dreaded his intelligence and nerve. He no longer did. In a curious way he was glad the Deaf Man had returned, but at the same time he sincerely wished the Deaf Man would go away. To return again? It was all very puzzling. Carella sighed and wheeled a typing cart into position near his desk.

From his own desk Willis said, “We don’t need him. Not at this time of year. Not with the warm weather starting.”

The clock on the squadroom wall read 10:51 A.M.

A half hour had passed since the Deaf Man’s last call. He had not called again, and Carella was not disappointed. As if to support Willis’s theory that the Deaf Man was not needed, not with the warm weather starting, the squadroom was now thronged with cops, lawbreakers, and victims — all on a nice quiet Friday morning with the sun shining in a clear blue sky, and the temperature sitting at seventy-two degrees.

There was something about the warm weather that brought them out like cockroaches. The cops of the 87th Precinct rarely enjoyed what could be called a “slow season,” but it did appear to them that less crimes were committed during the winter months. During the winter months, it was the firemen who had all the headaches. Slum landlords were not particularly renowned for their generosity in supplying adequate heat to tenement dwellers, despite the edicts of the Board of Health. The apartments in some of the buildings lining the side streets off Culver and Ainsley avenues were only slightly warmer than the nearest igloo. The tenants, coping with rats and faulty electrical wiring and falling plaster and leaking pipes, often sought to bring a little extra warmth into their lives by using cheap kerosene burners that were fire hazards. There were more fires in the 87th Precinct on any given winter’s night than in any other part of the city. Conversely, there were less broken heads. It takes a lot of energy to work up passion when you’re freezing your ass off. But winter had all but fled the city, and spring was here, and with it came the attendant rites, the celebrations of the earth, the paeans to life and living. The juices were beginning to flow, and nowhere did they flow as exuberantly as in the 87th, where life and death sometimes got a little bit confused and where the flowing juices were all too often a bright red.

Читать дальше