“Well, so we can get working on it. Also, I’m sure you want to report this to your insurance company.”

“None of it was insured.”

“Oh, boy,” Kling said.

“I just never thought anything like this would happen,” Augusta said.

“How long have you been living here?” Kling asked incredulously.

“The city or the apartment?”

“Both.”

“I’ve lived in the city for a year and a half. The apartment for eight months.”

“Where are you from originally?”

“Seattle.”

“Are you presently employed?” Kling said, and took out his pad.

“Yes.”

“Can you give me the name of the firm?”

“I’m a model,” Augusta said. “I’m represented by the Cutler Agency.”

“Were you in Austria on a modeling assignment?”

“No, vacation. Skiing.”

“I thought you looked familiar,” Ingersoll said. “I’ll bet I’ve seen your picture in the magazines.”

“Mmm,” Augusta said without interest.

“How long were you gone?” Kling asked.

“Two weeks. Well, sixteen days, actually.”

“Nice thing to come home to,” Ingersoll said again, and again shook his head.

“I moved here because it had a doorman,” Augusta said. “I thought buildings with doormen were safe.”

“ None of the buildings on this side of the city are safe,” Ingersoll said.

“Not many of them, anyway,” Kling said.

“I couldn’t afford anything across the park,” Augusta said. “I haven’t been modeling a very long time, I don’t really get many bookings.” She saw the question on Kling’s face and said, “The furs were gifts from my mother, and the jewelry was left to me by my aunt. I saved six goddamn months for the trip to Austria,” she said, and suddenly burst into tears. “Oh, shit,” she said, “why’d he have to do this?”

Ingersoll and Kling stood by awkwardly. Augusta turned swiftly, walked past Ingersoll to the sofa, and took a handkerchief from her handbag. She noisily blew her nose, dried her eyes, and said, “I’m sorry.”

“If you’ll let me have the complete list...” Kling said.

“Yes, of course.”

“We’ll do what we can to get it back.”

“Sure,” Augusta said, and blew her nose again.

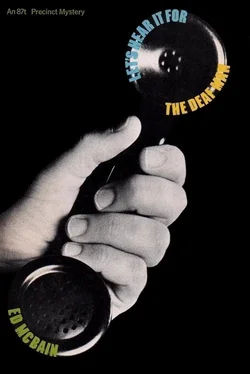

Everybody figured it was a mistake.

They were naturally grateful (who wouldn’t be?) to receive a second photostated picture of the late beloved leader of our nation’s finest security force, but they could not see any reason for it, and so they automatically figured somebody had goofed. It was unlike the Deaf Man to say anything twice when once would suffice. Nor was there any question but that the photostats were identical. The only difference between the one that had arrived in the mail on Saturday, April 17, and the one that arrived today, April 19, were the postmarks on the envelopes. But aside from that, everything was the same, an obvious error. The boys of the 87th were beginning to feel more cheerful about the entire matter; perhaps the Deaf Man was getting senile.

There were five pages of listings for photostat shops in the yellow pages of the Isola directory alone, and perhaps the police should have begun contacting each, on the off chance that one of them had copied Hoover’s picture. But nobody was forgetting that thus far no crime had been committed; you could not go around wasting the time of civil servants unless there was something that might conceivably justify such expense. One could, of course, argue that the Deaf Man’s past murderous exploits were reason enough for mobilizing the entire police department, getting those men out checking shops, clerks making telephone calls, mailing flyers, and so on. Conversely, one could just as reasonably argue that nobody really knew whether the two pictures of Hoover had indeed come from the Deaf Man, or whether they were in any way linked with the crime he had said he would commit. Given an overworked, understaffed police force with other pressing matters to worry about — like muggings, knifings, shootings, holdups, rapes, burglaries, forgeries, car thefts, oh you know, nuisance stuff — it was perhaps understandable why the cops of the 87th merely asked the laboratory whether the printing paper was unique and whether or not there were any good latent prints on it. The answers to both questions were depressing. The paper was garden-variety crap, and there were no latent prints on it, good or otherwise.

And then, because police work is not all fun and games and looking at pretty pictures, they got to work on a squeal that came in at 10:27 that morning.

The young man had been nailed to the tenement wall.

Long-haired, with a handlebar mustache, wearing only undershorts, he hung like a latter-day Christ bereft of wooden crucifix, a knife wound on the left side of his chest just below the heart, his arms widespread, a spike driven into the wall through each open palm, legs crossed and impaled with a third large spike, head lolling to the side. A vagrant wino had stumbled upon the body, but there was no telling how long he had been hanging there. The blood no longer ran from his wounds. He had soiled himself either in fright or in death, and his own rank stench mingled with the putrid stink of garbage in the empty room so that the detectives turned away from the open doorframe and went out into the corridor, where the air was only slightly less fetid.

The building was one in a long row of abandoned tenements on North Harrison, infested with rats, inhabited for a time by hippies, discarded by them later when they discovered it was too easy to be victimized there by men and beasts alike. The word LOVE still decorated a wall in the hallway, painted flowers running rampant around it in a faded circle, but the dead man in the empty room stank of his own excrement, and the assistant medical examiner did not want to go in to examine the corpse.

“Why should I get all the bad ones?” he asked Carella. “All the jobs nobody else wants, I get. The hell with it. He can rot in there, for all I care. Let the hospital people take him down and cart him to the morgue. We’ll examine him there, where at least I can wash my hands afterwards.”

The ceiling above their heads was bloated with water, the plaster dangerously loose and close to falling. The room in which the boy hung dead and crucified had one shattered window, and no door in its frame. It had been used as a makeshift garbage dump by the building’s squatters, and the garbage was piled three feet high, a thick carpet of moldering food, rusting cans, broken bottles, newspapers, used condoms, and animal feces, topped, as though with a maraschino cherry, with a swollen dead rat. For anyone to have entered the room, it would have been necessary to climb up onto the ledge formed by the garbage. The ceiling was perhaps twelve feet high, and the man’s impaled feet were crossed some six inches above the line of garbage. He was a tall young man. Whoever had driven the spikes through his extended hands had been even taller, but the body had sagged of its own weight since, dislocating both shoulders and wreaking God knew what internal damage.

“You hear me?” the M.E. said.

“Do what you like,” Carella answered.

“I will.”

“Just make sure we get a full necropsy report.”

“You think he was alive when they nailed him there?” Meyer asked.

“Maybe. The stabbing may have been an afterthought,” Carella said.

“I’m not taking him down, and that’s that,” the M.E. said.

“Look,” Carella said angrily, “take him down, leave him there, it’s up to you. Send us your goddamn report, and don’t forget prints.”

“I won’t.”

“Footprints, too.”

“More crazy bastards in this city,” the M.E. said, and walked off sullenly, picking his way through the rubble in the corridor, and starting down the staircase to the street, where he hoped to sell his case to the ambulance people when they arrived.

Читать дальше