“I wonder how they do that,” Tauber said. “Blind people.”

“They probably have some kind of instrument they use,” Carella said.

“Yeah, probably.”

“Do you think there’s anybody in the department who can translate this stuff?”

“You’ll probably have to go to Languages and Codes,” Tauber said.

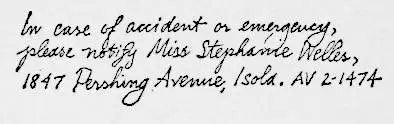

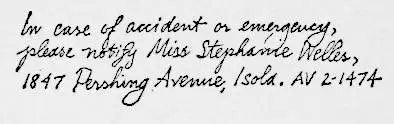

“Here’s something,” Carella said. He had turned to the inside back cover of the book. Pasted to it was a message in somewhat shaky longhand:

“Guess she figured...”

“Yeah,” Carella said.

“She had to write it in longhand, otherwise...”

“Yeah.”

“But it won’t do you no good, anyway,” Tauber said. “The address is an old one. She moved to Chicago six months ago.”

“Where in Chicago?”

“Someplace on Warrington Avenue.”

“Who is she?”

“The woman’s niece.”

“Any other relatives?”

“Not that I know of.”

“She should be contacted,” Carella said.

“You can check the apartment for letters soon as the lab boys are through. You might find an address.”

Before World War I, Pershing Avenue used to be called Grant Avenue. Architecturally, the wide esplanade looked much as it did then. A central divider planted with forsythia bushes and maple trees, leafless now in mid-November. Huge buildings on either side of the avenue, granite cornerstones, limestone facades. Spacious entry courts with concrete flowerpots sitting atop brick pedestals. In the days before World War I, the buildings lining Grant Avenue constituted some of the city’s choicest real estate. They were now scribbled over with graffiti advertising the name of this or that streetgang member. The graffiti was oversprayed — Spider 19 giving way to Dagger 21, in turn giving way to Salazar IV, so that nobody ’ s name meant a rat’s ass any more.

Maybe Spider 19 felt the same way Grant in heaven must have felt when they changed the name of the avenue to Pershing. Pershing himself had narrowly missed having the name changed again to Kennedy shortly after the assassination, when even lampposts were being named after the late President. Up there in heaven, old John Joseph, for such was the general’s name, most likely began muttering about sic transit gloria mundi and the high cost of changing street signs. But someone had the good sense to recognize that Roosevelt Street, some three blocks away from Pershing Avenue, had already had its name changed to Kennedy Street and another name-change of yet another thoroughfare might prove confusing to pedestrians and motorists alike. The people along Pershing Avenue were grateful. None of them knew General Pershing from a hole in the wall, and none of them would ever forget that bleak assassination day in November as long as they lived, so they didn’t need street names changed, they didn’t need that bullshit at all.

Carella parked his car two blocks from 1847 Pershing, the closest spot he could find, and began walking against the wind blowing through the naked chestnut trees. He had searched Hester Mathieson’s apartment for any back correspondence from Stephanie Welles and had found none; he guessed there was no reason for a blind woman to have saved letters that had to be read to her aloud. He had then called the post office serving the Pershing Avenue area to ask about a forwarding address that might have been filed six months ago, and the night clerk who answered the phone told him he’d have to call back in the morning, the only people there right now were sorting mail and moving it out. He then checked the address in Hester’s book against the Isola telephone directory and came up with an identical listing for Stephanie Welles. The possibility existed that she had sublet the apartment to someone she knew; Carella dialed the number. He let it ring twelve times, and then hung up.

It was ten p.m. by then.

Tauber had left the scene some forty minutes earlier, promising to check Homicide in an attempt to learn how the transfer to the Eight-Seven should be handled. When Carella called him at five past the hour, Tauber said he had spoken again to Young, and the Homicide cop would be sending out written authorization to the commanding officers at both Midtown East and the Eight-Seven, so that was that. He wished Carella luck with the case. Carella wanted to get a line on Stephanie Welles now, tonight, before this one began to get cold, too. He drove to Pershing Boulevard hoping for one of two things: either the person who’d rented the apartment after her knew where Stephanie Welles was now living in Chicago, or else Stephanie had left a forwarding address with the superintendent of the building. He was less interested in notifying her of her aunt’s death than he was in soliciting information from her. He did not know how much she knew about the dead woman’s habits or acquaintances, but she’d been listed as the person to call in case of an emergency or an accident, and Hester Mathieson had suffered the biggest accident of them all.

He walked with his head ducked.

The wind was shrill.

He saw the graffiti-marked buildings, and tried to understand — but could not.

His grandfather had come to America from Italy because he’d been told the streets here were paved with gold. They were not, of course, and Giovanni Carella learned that almost at once, driving a horse and wagon for the milk company, the horse dropping the only golden nuggets anywhere in view. Nor were the streets as clean as those to be found in Giovanni’s native Naples, or so Giovanni claimed, a premise perhaps disputable. But in those days, when Carella’s grandfather first got here at the turn of the century, the European sense of tradition and of place caused immigrants like himself to look upon even their slum dwellings as something to be cared for with pride. The buildings — your own building and the building next door and the one next door to that — were home. Together they formed “la vicinanza” and you did not defile your home, you did not shit where you ate. No one would have dreamt of scribbling upon the face of a tenement, however grim the building was. No one would have marked a trolley car — the subways were in the process of being built, there were no subway cars to mark — because these were people who had lived with beauty centuries-old, and they were not yet used to the fact that in America things existed only to be changed or destroyed.

Carella climbed the flat wide steps of the front stoop, past a pair of empty concrete urns, each scribbled over with undecipherable names. He moved across the courtyard toward the entrance doors of the building. Two young boys were playing boxball in the illuminated courtyard. They looked up at him as he went past, and then went back to their game. He entered the outer lobby of the building, and was searching the mailboxes for the super’s apartment number when he came across the name S. WELLES in the slot under the mailbox for apartment 54. He didn’t know exactly what this meant. Had Stephanie Welles kept the apartment here in Isola while living in Chicago? Or had it been sublet or otherwise rented to someone who’d simply neglected to change the name in the box?

He pressed the bell-button under the box. Nothing. He pressed it again, ready to reach for the inner-lobby door when the buzz sounded. Nothing came. At the end of the row of mailboxes, he found the super’s box, and pressed the button under it. He waited several moments and was about to press it again when an answering buzz came. Leaping for the handle on the lobby door, he opened the door and stepped into a larger space that was dry with contained heat. Against the wall on his left, a pair of radiators hissed and whistled. A single elevator with a pair of spray-painted brass doors was on the rear wall. On the right of the lobby, taped to the wall there, Carella saw a piece of cardboard with the word Super hand-lettered onto it, a black arrow under it. He followed the arrow and knocked on the door to apartment 10. A man’s voice said, “Yeah, who is it?”

Читать дальше