“That guy’s going to Riverhead,” the cabbie said, turning to Teddy. “See, he’s crossing the bridge. You sure you want me to follow him?”

Teddy nodded. Riverhead. She lived in Riverhead. She and Steve lived in Riverhead, but Riverhead was a big part of the city. Where in Riverhead was the man taking the girl? And where was Steve? Was he at the squad? Was he home? Was he still out canvassing tattoo parlors? Was it possible he’d visit Charlie Chen again? she wondered. She tore off a slip of paper, putting it with the growing pile of slips beside her on the seat. Then she began writing again.

And then, as if to check the accuracy of her first observation, she looked at the rear of Donaldson’s car again.

“Are you a writer or something?” the cabbie asked.

It bothered Kling.

He got up and walked to where Havilland was reading a true detective magazine, his feet propped up on the desk.

“What’d you say that guy’s name was?”

“What?” Havilland asked, looking up from the magazine. “Here’s a case about a guy who cut up his victims. Put them in trunks.”

“This guy who called for Steve,” Kling said. “What’d you say his name was?”

“A crackpot. Sam Spade or something.”

“Didn’t you say Charlie Chan?”

“Yeah, Charlie Chan. A crackpot.”

“What’d he say to you?”

“Said Carella’s tattoo design was in the shop. Said he’d try to keep it there.”

“Charlie Chen,” Kling said, thoughtfully. “Carella questioned him. Chen. He was the man who tattooed Mary Proschek.” He thought again. Then he said, “What’s his number?”

“He didn’t leave any,” Havilland said.

“It’s probably in the book,” Kling said, starting back for his own desk.

“The hell of this thing is that the cops didn’t tip to this guy for three years,” Havilland said, wagging his head. “Cutting up dames for three years and they didn’t tip.” He wagged his head again. “Jesus, how could they be so stupid!”

“It looks like he’s pulling over, lady,” the cabbie said. “You want I should pull in right behind him?”

Teddy shook her head.

The cabbie sighed. “So where, then? Right here okay?” Teddy nodded. The cabbie pulled in and stopped his meter. Up ahead, Donaldson had parked and was helping Priscilla from the car. Teddy watched them as she fished in her purse for money to pay the cabbie. She paid him, and then she scooped up the pile of paper slips from the seat beside her. She handed one to the cabbie, stepped out, and began running because Donaldson and Priscilla had just turned the corner.

“What...” the cabbie said, but his fare was gone.

He looked at the narrow slip of paper. In a hurried hand, Teddy had written:

Call Detective Steve Carella, FRederick 7-8024. Tell him license number is DN1556. Hurry please!

The cabbie stared at the note.

He sighed heavily.

“Women writers!” he said aloud, and he crumpled the slip, threw it out the window, and gunned away from the curb.

Kling found the number in the classified. He asked the desk sergeant for a line, and then he dialed.

He could hear the phone ringing on the other end. Methodically, he began counting the rings.

Three...four...five...

Kling waited.

Six...seven...eight...

Come on, Chen, he thought. Answer the damn thing!

And then he remembered the message Chen had given Havilland: He would try to keep the tattoo design in the shop. Jesus, had something happened to Chen?

He hung up on the tenth ring.

“I’m checking out a car,” he shouted to Havilland. “I’ll be back later.”

Havilland looked up from his magazine. “What?” he asked.

But Kling was already through the gate in the slatted railing and heading for the steps leading to the first floor.

Besides, the phone on Havilland’s desk was ringing.

Chen was walking away from the shop when he heard the telephone. He had left the shop a moment earlier, fired with the decision to go directly to the 87th Precinct, find Carella, and tell him what had happened. He had locked up and was walking toward his car when the telephone began ringing.

Perhaps there is no difference in the way a telephone rings. It does not ring differently for sweethearts making lovers’ calls, it does not ring differently when it carries bad news, or when it carries news of a big deal being closed.

Chen was in a hurry. He had to see Carella, had to talk to him.

So perhaps the ring of the telephone in his closed and locked shop was not really so urgent. Perhaps it did not really sound so terribly important. It was, after all, only a telephone ring.

It was, nonetheless, urgent-sounding enough to pull him back from the curb and over to the locked door. It sounded urgent enough to force him to reach for his keys rapidly, find the right key, shove it into the hanging padlock, snap open the lock, and then throw open the door and rush to the phone.

It sounded urgent as hell until it stopped ringing.

By the time Chen lifted the receiver, all he got was a dial tone.

And since he had a dial tone, he used it.

He called FRederick 7-8024.

“87th Precinct, Sergeant Murchison,” the voice said.

“Detective Carella, please,” Chen said.

“Second,” the desk sergeant answered. Chen waited. He was right, then. Carella was back. He listened to the clicking on the line.

“87th Squad, Detective Havilland,” Havilland said.

“I speak to Detective Carella, please?”

“Not here,” Havilland said. “Who’s this?” From the corner of his eye, he saw Kling disappear into the stairwell leading to the first floor.

“Charlie Chen. When he be back?”

“Just a second,” Havilland said. He covered the mouthpiece. “Hey, Bert!” he shouted. “Bert!” There was no answer from the stairwell. Into the phone, Havilland said, “I’m a cop, too, mister. What’s on your mind?”

“Man who tattoo girl,” Chen said. “He was here shop. With Mrs. Carella.”

“Slow down,” Havilland said. “What man? What girl?”

“Carella knows,” Chen said. “Tell him man’s name is Chris. Big, blond man. Tell him wife follows. When he be back? Don’t you know when he be back?”

“Listen—” Havilland started, and Chen impatiently said, “I come. I come tell him. You ask him wait.”

“He may not even—” Havilland said, but he was talking to a dead line.

The girl was bent over double, the handkerchief pressed to her mouth. The tall, blond man kept his arm around her waist, holding her up, half walking her, half dragging her down the street.

Behind them, Teddy Carella followed.

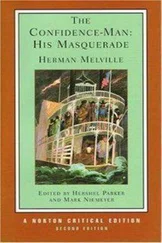

Teddy Carella knew very little about con men.

She knew, though, that you could stand on a corner and offer to sell $5 gold pieces for 10¢, and you wouldn’t get a buyer all day. She knew that the city was an inherently distrustful place, that strangers did not talk to strangers in restaurants, that people somehow did not trust people.

And so she had taken out insurance.

If she had a tongue, she’d have shouted her message.

She could not speak, and so she’d taken insurance that would shout her message, a dozen narrow slips of paper, with the identical message on each slip:

Call Detective Carella, FRederick 7-8024. Tell him license number is DN1556. Hurry please!

And now, as she followed along behind Donaldson and the girl, she began to shout her message. She could not linger long with each passerby because she could not afford to lose sight of the pair. She could only touch the sleeve of an old man and hand him the paper and then walk off. She could only gently press the dip into the hand of a matron in a gray dress and leave her puzzled and somewhat amused. She could only stop a teenager, avoid the open invitation in his eyes, and hand him the message. She left behind her a trail of people with a scrap of paper in their hands. She hoped that one of them would call the 87th. She hoped the license number would reach her husband. In the meantime, she followed a sick girl and a killer, and she didn’t know what she would do if her husband didn’t reach her, if her husband didn’t somehow reach her.

Читать дальше