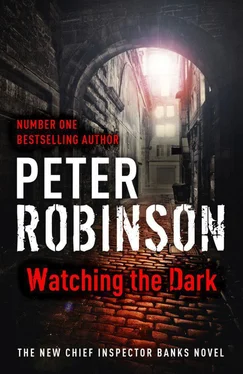

Peter Robinson

Watching the Dark

On nights when the pain kept her awake, Lorraine Jenson would get up around dawn and go outside to sit on one of the wicker chairs before anyone else in the centre was stirring. With a tartan blanket wrapped around her shoulders to keep out the early morning chill, she would listen to the birds sing as she enjoyed a cup of Earl Grey, the aromatic steam curling from its surface, its light, delicious scent filling her nostrils. She would smoke her first cigarette of the day, always the best one.

Some mornings, the small artificial lake below the sloping lawn was covered in mist, which shrouded the trees on the other side. Other times, the water was a still, dark mirror that reflected the detail of every branch and leaf perfectly. On this fine April morning, the lake was clear, though the water’s surface was ruffled by a cool breeze, and the reflections wavered.

Lorraine felt her pain slough off like a layer of dead skin as the painkillers kicked in, and the tea and cigarette soothed her frayed nerves. She placed her mug on the low wrought-iron table beside her chair and adjusted the blanket around her shoulders. She was facing south, and the sun was creeping over the hill through the trees on her left. Soon the spell would be broken. She would hear the sounds of people getting up in the building behind her, voices calling, doors opening, showers running, toilets flushing, and another day to be got through would begin.

As the light grew stronger, she thought she could see something, like a bundle of clothes, on the ground at the edge of the woods on the far side of the lake. That was unusual, as Barry, the head groundsman and general estate manager, was proud of his artificial lake and his natural woodlands, so much so that some people complained he spent far more time down there than he did keeping the rest of the extensive grounds neat and tidy.

Lorraine squinted, but she couldn’t bring the object into clearer focus. Her vision was still not quite what it had been. Gripping the arms of her chair, she pushed herself to her feet, gritting her teeth at the red-hot pokers of pain that seared through her left leg, despite the OxyContin, then she took hold of her crutch and made her way down the slope. The grass was still wet with dew, and she felt it fresh and cool on her bare ankles as she walked.

When she got to the water’s edge, she took the cinder path that skirted the lake and soon arrived on the other side, at the edge of the woods, which began only a few feet away from the water. Even before then, she had recognised what it was that lay huddled there. Though she had seen dead bodies before, she had never actually stumbled across one. She was alone with the dead now, for the first time since she had stood by her father’s coffin in the funeral home.

Lorraine held her breath. Silence. She thought she heard a rustling deep in the woods, and a shiver of fear rippled through her. If the body were a victim of murder, then the killer might still be out there, watching her. She remained completely still for about a minute, until she was certain there was nobody in the woods. She heard the rustling again and saw a fox making its way through the undergrowth.

Now that she was at the scene, Lorraine’s training kicked in. She was wary of disturbing anything, so she kept her distance. Much as she wanted to move in closer and examine the body, see if it was someone she knew, she restrained herself. There was nothing she could do, she told herself; the way he — for it was definitely a man — was kneeling with his body bent forward, head touching the ground like a parody of a Muslim at prayer, there was no way he was still alive.

The best thing she could do was stay here and protect the scene. Murder or not, it was definitely a suspicious death, and whatever she did, she must not screw up now. Cursing the pain that rippled through her leg whenever she moved, Lorraine fumbled for her mobile in her jeans pocket and phoned Eastvale police station.

There was something about Bach that suited the early morning perfectly, DCI Alan Banks thought, as he drove out of Gratly towards the St Peter’s Police Convalescence and Treatment Centre, four miles north of Eastvale, shortly after dawn that morning. He needed something to wake him up and keep his attention engaged, get the old grey cells buzzing, but nothing too loud, nothing too jarring or emotionally taxing. Alina Ibragimova’s CD of Bach’s sonatas and partitas for violin was just right. Bach both soothed and stimulated the mind at once.

Banks knew St Peter’s. He had visited Annie Cabbot there several times during her recent convalescence. Just a few short months ago he had seen her in tears trying to walk on crutches, and now she was due back at work on Monday. He was looking forward to that; life had been dull for the past while without her.

He took the first exit from the roundabout and drove alongside the wall for about a hundred yards before arriving at the arched entrance and turning left on the tarmac drive. There was no gate or gatehouse, but the first officers to arrive on the scene had quite rightly taped off the area. A young PC waved Banks down to check his ID and note his name and time of entry on a clipboard before lifting the tape and letting him through.

Driving up to the car park was like arriving at a luxury spa hotel, Banks had always thought when he visited Annie. It was no different today. St Peter’s presented a broad south-facing facade at the top of the rise that led down to the lake and surrounding woods. Designed by a firm of Leeds architects, with Vanburgh in mind, and built of local stone in the late nineteenth century, it was three stories high, had a flagged portico, complete with simple Doric columns at the front, and two wings, east and west. Though not so extensive as some other local examples, the grounds were landscaped very much in the style and spirit of Capability Brown, with the lake and woods and rolling lawns. There was even a folly. To the west, beyond the trees and lawns, the outlines of Swainsdale’s hills and fells could be seen, forming a backdrop of what the Japanese called borrowed scenery, which merged nature with art.

The forensic team had got there before Banks, which seemed odd until he remembered that a detective inspector had made the initial call. Kitted out in disposable white coveralls, they were already going about their business. The crime-scene photographer, Peter Darby, was at work with his battered old Nikon SLR and his ultra-modern digital video recorder. Most SOCOs — or CSIs, as they now liked to be called — also took their own digital photos and videos when they searched a scene, but though Peter Darby accepted the use of video, he shunned digital photography as being far too susceptible to tampering and error. It made him a bit of a dinosaur, and one or two of the younger techies cracked jokes behind his back. He could counter by boasting that he had never had any problems with his evidence in court, and he had never lost an image because of computer problems.

DI Lorraine Jenson stood with two other people about five or six yards away from the body, a lone, hunched figure resting her weight on a crutch by the water’s edge and jotting in her notebook. Banks knew her slightly from a case he had worked a few months ago that crossed the border into Humberside, where she worked. Not long ago, he had heard, she had a run in with a couple of drug-dealers in a tower block, which ended with her falling from a second-floor balcony. She had sustained multiple fractures of her left leg, but after surgery, the cast and physio, she would be back at work soon enough.

‘What a turn up,’ she said. ‘Me finding a body.’

Читать дальше